Why Being Great Is So Much Harder Than People Realize

“What’s going on here? What does this say about how greatness is achieved?”

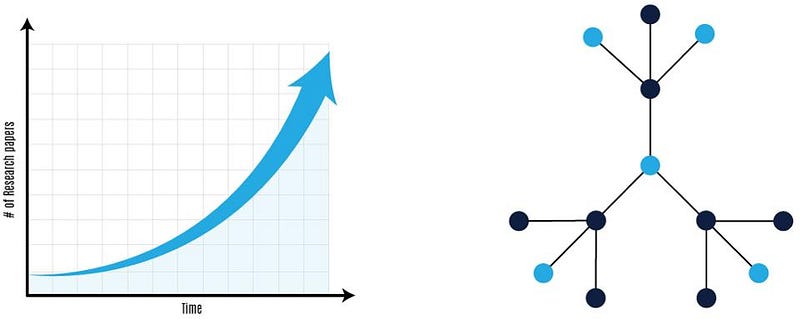

In this article, I make the case that what we’re seeing here is a pattern that happens across almost all fields and industries: The amount to learn in order to be great is increasing exponentially.

- To get a quick start, competitors first copy the best practices of the top performers.

- Once they hit the best practice frontier, they then focus on experimentation. These experiments are often informed by best practices from other fields and new tools. In other words, they follow Pablo Picasso’s advice of “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

- Most experiments fail, but the ones that succeed become best practices and are copied by others.

- The body of knowledge that one must master in order to be great increases.

- Knowledge is always becoming outdated. However, occasionally, completely new paradigms arise where large bundles of old best practices become obsolete and early adopters create a bundle of new practices that create a new paradigm.

The history of running backs this up. Throughout the period when world records were improving, so too were the training paradigms: from intensity training to interval training to a focus on endurance. Each generation built upon the previous generation’s lessons and built new paradigms for training, technique, equipment and health. Or as Isaac Newton eloquently said:

“If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.”

Running is a microcosm of what’s happening in the work world as knowledge explodes (social media content is doubling every year, digital information is increasing tenfold every five years, academic research is doubling every nine years). This explosion creates exponentially more “best practices” for us to build upon if we want to be great.

We must also learn more because our existing knowledge is becoming obsolete at a faster and faster rate. One academic study, for example, found that the decay rate in the accuracy of clinical knowledge about cirrhosis and hepatitis was 45 years. In other words, if you’re talking to a 70-year-old liver specialist who hasn’t updated his skills, you have a 50 percent chance of getting bad information. Engineering degrees went from a half life of 35 years in 1930 to about 10 years in 1960.

The explosion of knowledge and the corresponding decay make one thing clear: we need to put a bigger priority on constant learning — as big an emphasis as we put on getting our optimal daily dose of nutrients, exercise, and sleep.

The Law Of Accelerated Intelligence

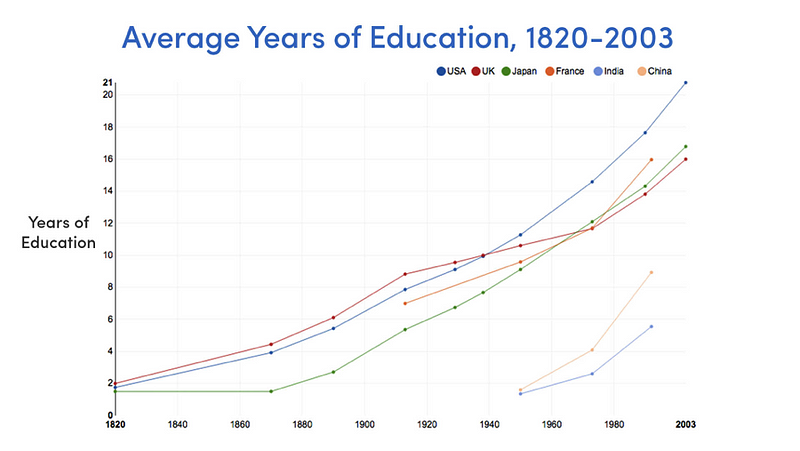

According to Our World In Data, the average person in developed societies has been spending more and more time learning in formal settings over the last two centuries.

Source: Our World In Data: Global Rise Of EducationThe same holds true with informal learning outside of traditional institutions, which accounts for 70 to 90 percent of all learning. Podcasts, videos, articles, games, and digital courses give people the ability to learn almost anything online for free.

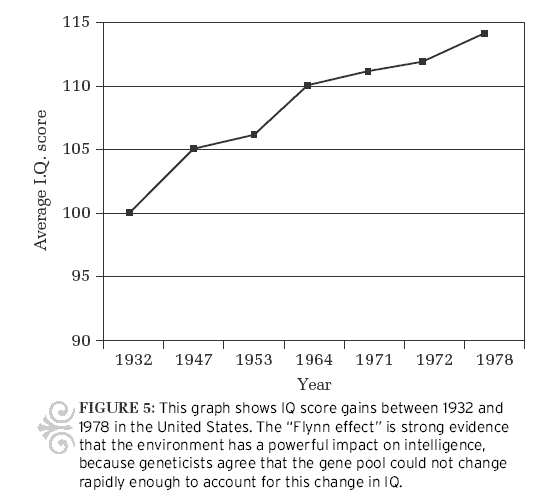

A similar trend is happening with intelligence. One of the most surprising trends in psychology is called the Flynn Effect. It shows how intelligence test scores, which historically have been thought of as “fixed,” have continued to rise in many parts of the world over the past century.

Why is this all happening? I’d argue that the reason is what I call the Law of Accelerated Intelligence:

As our amount of accumulated knowledge increases exponentially, the minimum amount of learning we need to do in order to productively participate or be a top performer in society increases. In other words, accelerated societal change necessitates accelerated intelligence.

Or as economist Ben Jones puts it, “If one is to stand on the shoulders of giants, one must first climb up their backs, and the greater the body of knowledge, the harder this climb becomes.”

We’ve already felt this in our own daily lives too. When I first learned web design, all I needed to know was HTML and how to use Adobe Photoshop. Now, a web designer is expected to understand other languages too, understand how to do testing and analytics, and how to use a huge suite of other tools. And whether your career is web design, sales, journalism, or real estate, the digital world generated dozens of new skills to master.

For example, data science, programming, and artificial intelligence used to be niche skills. Now, having a basic understanding of them is more and more important for more and more professions. It’s no longer enough to just get a degree or take a professional development course once a year. The learning needs to be constant.

Just like with running, being among the best gets more and more demanding with each passing year. Each generation of champions develops a body of best practices. The next generation must learn them and then build upon them, leaving those who come after them with even more to learn to get up to speed. And the cycle continues.

Granted, the process of creative destruction where new industries and fields form provides windows of opportunity where people with new, important knowledge can leapfrog others with more overall experience. Many great tech entrepreneurs have been able to succeed at a young age by devoting years of deliberate learning to a new field before anybody else. But, their success doesn’t mean that they can slow down their own learning. In fact, it often means that they need to speed it up.

Predicting The Future Of Learning

In 1965, Gordon Moore, one of the co-founders of Intel, noticed an interesting pattern: the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubled every two years historically.

This underlying pattern has had a profound effect on society. For example, your current smartphone has more computing power than the mainframes NASA used to run Apollo missions back in the ’60s. Furthermore, knowledge of Moore’s Law has made it possible to make remarkably accurate predictions of the future. It has also become a self-fulfilling prophecy: Intel, for example, plans their innovation cycles of chips partially around Moore’s Law.

The Law Of Accelerated Intelligence has lasted for many decades, and perhaps for hundreds of years. We as individuals and as societies should plan our future around it, just as the technology industry plans its future around Moore’s Law.

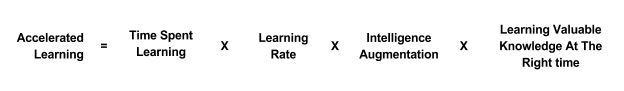

The Law Of Accelerated Intelligence Formula

People who want to be top performers now and in the future need to optimize this Accelerated Learning Formula:

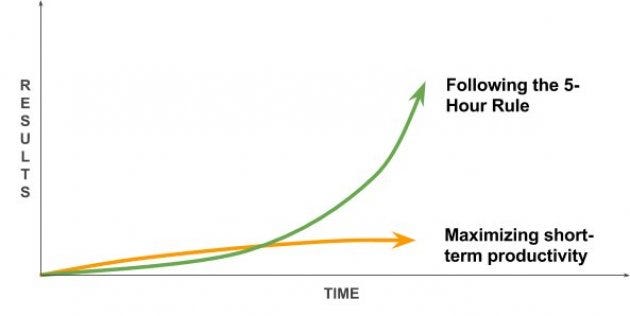

Time Spent Learning: As I make the case for in 5-Hour Rule: If you’re not spending 5 hours per week learning, you’re being irresponsible and Bill Gates, Warren Buffett And Oprah All Use The 5-Hour Rule, the minimum amount of learning that professionals should do on a weekly basis is 5 hours.

Learning Rate: We do have the ability to increase our learning rate. This ability is not dependent on our intelligence. It’s dependent on mastering the skill of learning how to learn. Mastering this skill early allows the benefit of the skill to compound throughout one’s life.

Intelligence Augmentation: We live in a time when our own intelligence can be dramatically amplified by affordable, powerful tools. For example, one class of tools help us to build larger, more connected, more diverse networks that augment our own intelligence and allow us to accomplish more on teams than we could on our own. Another class of tools allow us to find and build datasets of the actions and results of top performers in our industry so we can algorithmically understand the subtle patterns of greatness. Taking the time to learn about these tools and methods will become more and more critical.

Identify valuable knowledge at the right time. The value of knowledge isn’t static. It changes as a function of how valuable other people consider it and how rare it is. As new technologies mature and reshape industries, there is often a deficit of people with the needed skills, which creates the potential for high compensation. Because of the high compensation, more people are quickly trained, and the average compensation decreases.

Interested in applying the Law of Accelerated Learning Formula to your life? Over the last three years, I’ve researched how some of the world’s best learners and most successful entrepreneurs find the time to learn, stay consistent in their learning ritual, and get more results from their time. There was too much information for one article, so I spent dozens of hours and created a free masterclass to help you master your learning ritual too!

Sign up for the free Learning How To Learn webinar here >>

Join The Discussion

I’m interested in improving the thinking behind this thesis. The best way to improve thinking is by challenging it. To that end, there is a great discussion going on in our Learning How To Learn Facebook Group (40,000+ members). Join the thread by clicking here.

5-Hour Rule: If you’re not spending 5 hours per week learning, you’re being irresponsible

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none. Zero.”

— Charlie Munger, Self-made billionaire & Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner

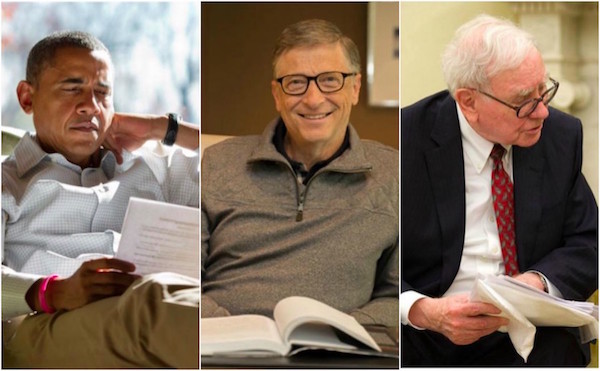

Why did the busiest person in the world, former president Barack Obama, read an hour a day while in office?

Why has the best investor in history, Warren Buffett, invested 80% of his time in reading and thinking throughout his career?

Why has the world’s richest person, Bill Gates, read a book a week during his career? And why has he taken a yearly two-week reading vacation throughout his entire career?

Why do the world’s smartest and busiest people find one hour a day for deliberate learning (5-hour rule), while others make excuses about how busy they are?

What do they see that others don’t?

The answer is simple: Learning is the single best investment of our time that we can make. Or as Benjamin Franklin said, “An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

This insight is fundamental to succeeding in our knowledge economy, yet few people realize it. Luckily, once you do understand the value of knowledge, it’s simple to get more of it. Just dedicate yourself to constant learning.

Knowledge is the new money

“Intellectual capital will always trump financial capital.” — Paul Tudor Jones, self-made billionaire entrepreneur, investor, and philanthropist

We spend our lives collecting, spending, lusting after, and worrying about money — in fact, when we say we “don’t have time” to learn something new, it’s usually because we are feverishly devoting our time to earning money, but something is happening right now that’s changing the relationship between money and knowledge.

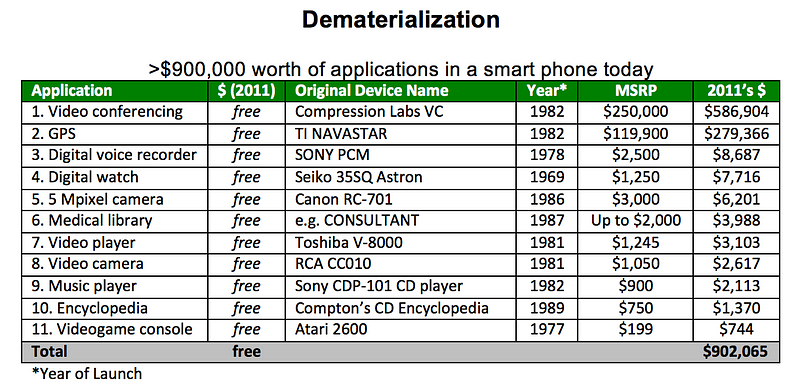

We are at the beginning of a period of what renowned futurist Peter Diamandis calls rapid demonetization, in which technology is rendering previously expensive products or services much cheaper — or even free.

This chart from Diamandis’ book Abundance shows how we’ve demonetized $900,000 worth of products and services you might have purchased between 1969 and 1989.

This demonetization will accelerate in the future. Automated vehicle fleets will eliminate one of our biggest purchases: a car. Virtual reality will make expensive experiences, such as going to a concert or playing golf, instantly available at much lower cost. While the difference between reality and virtual reality is almost incomparable at the moment, the rate of improvement of VR is exponential.

While education and health care costs have risen, innovation in these fields will likely lead to eventual demonetization as well. Many higher educational institutions, for example, have legacy costs to support multiple layers of hierarchy and to upkeep their campuses. Newer institutions are finding ways to dramatically lower costs by offering their services exclusively online, focusing only on training for in-demand, high-paying skills, or having employers who recruit students subsidize the cost of tuition.

Finally, new devices and technologies, such as CRISPR, the XPrize Tricorder, better diagnostics via artificial intelligence, and reduced cost of genomic sequencing will revolutionize the healthcare system. These technologies and other ones like them will dramatically lower the average cost of healthcare by focusing on prevention rather than cure and management.

While goods and services are becoming demonetized, knowledge is becoming increasingly valuable.

“The central event of the twentieth century is the overthrow of matter. In technology, economics, and the politics of nations, wealth in the form of physical resources is steadily declining in value and significance. The powers of mind are everywhere ascendant over the brute force of things.” —George Gilder (technology thinker)

Perhaps the best example of the rising value of certain forms of knowledge is the self-driving car industry. Sebastian Thrun, founder of Google X and Google’s self-driving car team, gives the example of Uber paying $700 million for Otto, a six-month-old company with 70 employees, and of GM spending $1 billion on their acquisition of Cruise. He concludes that in this industry, “The going rate for talent these days is $10 million.”

That’s $10 million per skilled worker, and while that’s the most stunning example, it’s not just true for incredibly rare and lucrative technical skills. People who identify skills needed for future jobs — e.g., data analyst, product designer, physical therapist — and quickly learn them are poised to win.

Those who work really hard throughout their career but don’t take time out of their schedule to constantly learn will be the new “at-risk” group. They risk remaining stuck on the bottom rung of global competition, and they risk losing their jobs to automation, just as blue-collar workers did between 2000 and 2010 when robots replaced 85 percent of manufacturing jobs.

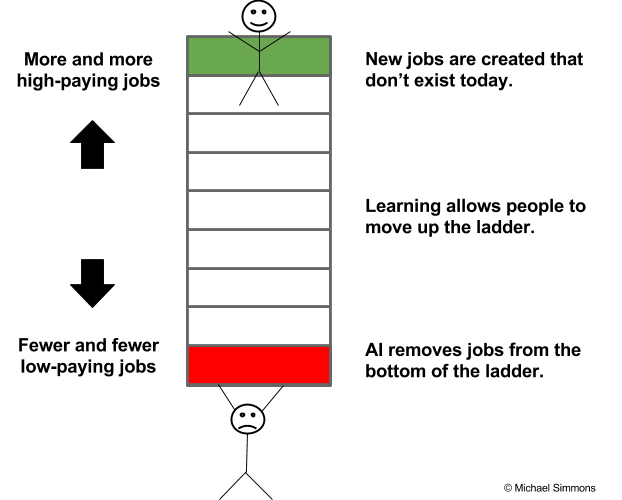

Why?

People at the bottom of the economic ladder are being squeezed more and compensated less, while those at the top have more opportunities and are paid more than ever before. The irony is that the problem isn’t a lack of jobs. Rather, it’s a lack of people with the right skills and knowledge to fill the jobs.

An Atlantic article captures the paradox: “Employers across industries and regions have complained for years about a lack of skilled workers, and their complaints are borne out in U.S. employment data. In July [2015], the number of job postings reached its highest level ever, at 5.8 million, and the unemployment rate was comfortably below the post-World War II average. But, at the same time, over 17 million Americans are either unemployed, not working but interested in finding work, or doing part-time work but aspiring to full-time work.”

In short, we can see how at a fundamental level knowledge is gradually becoming its own important and unique form of currency. In other words, knowledge is the new money. Similar to money, knowledge often serves as a medium of exchange and store of value.

But, unlike money, when you use knowledge or give it away, you don’t lose it. In fact, it’s the opposite. The more you give away knowledge, the more you:

- Remember it

- Understand it

- Connect it to other ideas in your head

- Build your identity as a role model for that knowledge

Transferring knowledge anywhere in the world is free and instant. Its value compounds over time faster than money. It can be converted into many things, including things that money can’t buy, such as authentic relationships and high levels of subjective well-being. It helps you accomplish your goals faster and better. It’s fun to acquire. It makes your brain work better. It expands your vocabulary, making you a better communicator. It helps you think bigger and beyond your circumstances. It connects you to communities of people you didn’t even know existed. It puts your life in perspective by essentially helping you live many lives in one life through other people’s experiences and wisdom.

Former President Obama perfectly explains why he was so committed to reading during his Presidency in a recent New York Times interview:

“At a time when events move so quickly and so much information is transmitted,” he said, reading gave him the ability to occasionally “slow down and get perspective” and “the ability to get in somebody else’s shoes.” These two things, he added, “have been invaluable to me. Whether they’ve made me a better president I can’t say. But what I can say is that they have allowed me to sort of maintain my balance during the course of eight years, because this is a place that comes at you hard and fast and doesn’t let up.”

6 essentials skills to master the new knowledge economy

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” — Alvin Toffler

So, how do we learn the right knowledge and have it pay off for us? The six points below serve as a framework to help you begin to answer this question. I also created an in-depth webinar on Learning How To Learn that you can watch for free.

- Identify valuable knowledge at the right time. The value of knowledge isn’t static. It changes as a function of how valuable other people consider it and how rare it is. As new technologies mature and reshape industries, there is often a deficit of people with the needed skills, which creates the potential for high compensation. Because of the high compensation, more people are quickly trained, and the average compensation decreases.

- Learn and master that knowledge quickly. Opportunity windows are temporary in nature. Individuals must take advantage of them when they see them. This means being able to learn new skills quickly. After reading thousands of books, I’ve found that understanding and using mental models is one of the most universal skills that EVERYONE should learn. It provides a strong foundation of knowledge that applies across every field. So when you jump into a new field, you have preexisting knowledge you can use to learn faster.

- Communicate the value of your skills to others. People with the same skills can command wildly different salaries and fees based on how well they’re able to communicate and persuade others. This ability convinces others that the skills you have are valuable is a “multiplier skill.” Many people spend years mastering an underlying technical skill and virtually no time mastering this multiplier skill.

- Convert knowledge into money and results. There are many ways to transform knowledge into value in your life. A few examples include finding and getting a job that pays well, getting a raise, building a successful business, selling your knowledge as a consultant, and building your reputation by becoming a thought leader.

- Learn how to financially invest in learning to get the highest return. Each of us needs to find the right “portfolio” of books, online courses, and certificate/degree programs to help us achieve our goals within our budget. To get the right portfolio, we need to apply financial terms — such as return on investment, risk management, hurdle rate, hedging, and diversification — to our thinking on knowledge investment.

- Master the skill of learning how to learn. Doing so exponentially increases the value of every hour we devote to learning (our learning rate). Our learning rate determines how quickly our knowledge compounds over time. Consider someone who reads and retains one book a week versus someone who takes 10 days to read a book. Over the course of a year, a 30% difference compounds to one person reading 85 more books.

To shift our focus from being overly obsessed with money to a more savvy and realistic quest for knowledge, we need to stop thinking that we only acquire knowledge from 5 to 22 years old, and that then we can get a job and mentally coast through the rest of our lives if we work hard. To survive and thrive in this new era, we must constantly learn.

Working hard is the industrial era approach to getting ahead. Learning hard is the knowledge economy equivalent.

Just as we have minimum recommended dosages of vitamins, steps per day, and minutes of aerobic exercise for maintaining physical health, we need to be rigorous about the minimum dose of deliberate learning that will maintain our economic health. The long-term effects of intellectual complacency are just as insidious as the long-term effects of not exercising, eating well, or sleeping enough. Not learning at least 5 hours per week (the 5-hour rule) is the smoking of the 21st century and this article is the warning label.

Don’t be lazy. Don’t make excuses. Just get it done.

“Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.” — Mahatma Gandhi

Before his daughter was born, successful entrepreneur Ben Clarke focused on deliberate learning every day from 6:45 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. for five years (2,000+ hours), but when his daughter was born, he decided to replace his learning time with daddy-daughter time. This is the point at which most people would give up on their learning ritual.

Instead of doing that, Ben decided to change his daily work schedule. He shortened the number of hours he worked on his to do list in order to make room for his learning ritual. Keep in mind that Ben oversees 200+ employees at his company, The Shipyard, and is always busy. In his words, “By working less and learning more, I might seem to get less done in a day, but I get dramatically more done in my year and in my career.” This wasn’t an easy decision by any means, but it reflects the type of difficult decisions that we all need to start making. Even if you’re just an entry-level employee, there’s no excuse. You can find mini learning periods during your downtimes (commutes, lunch breaks, slow times). Even 15 minutes per day will add up to nearly 100 hours over a year. Time and energy should not be excuses. Rather, they are difficult, but overcomable challenges. By being one of the few people who rises to this challenge, you reap that much more in reward.

We often believe we can’t afford the time it takes, but the opposite is true: None of us can afford not to learn.

Learning is no longer a luxury; it’s a necessity.

Start your learning ritual today with these three steps

The busiest, most successful people in the world find at least an hour to learn EVERY DAY. So can you!

Just three steps are needed to create your own learning ritual:

- Find the time for reading and learning even if you are really busy and overwhelmed.

- Stay consistent on using that “found” time without procrastinating or falling prey to distraction.

- Increase the results you receive from each hour of learning by using proven hacks that help you remember and apply what you learn.

Over the last three years, I’ve researched how top performers find the time, stay consistent, and get more results. There was too much information for one article, so I spent dozens of hours and created a free masterclass to help you master your learning ritual too!

How One Life Hack From A Self-Made Billionaire Leads To Exceptional Success

Countless books and articles have been written about Warren Buffett. Surprisingly few have been written about his business partner of over 40 years, Charlie Munger.

Munger has stayed out of the public eye, giving only a small number of public talks, and he’s rarely been covered in the media. At Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholder’s meetings, he lets Buffett answer the questions, often times commenting, “I have nothing to add.”

A few years ago, I decided to learn more about Munger’s 70-year career, and I’ve been blown away ever since. When I look back on my life, I see it has one of the top turning points in my life. His model for success, backed by research, is simple and game-changing. It also flies in the face of conventional wisdom on career success.

Beyond The 10,000 Hour Rule

A great deal has been written about how deliberate practice over 10,000 hours within a specific area of expertise is the key to success in any field.

While Munger has certainly worked long and hard to become one of the world’s top investors, the signature of his success is different. According to his own account, rather than focusing on investment theory like a laser, he has studied widely and deeply in many fields, including microeconomics, psychology, law, mathematics, biology, and engineering, and applied insights from them to investing.

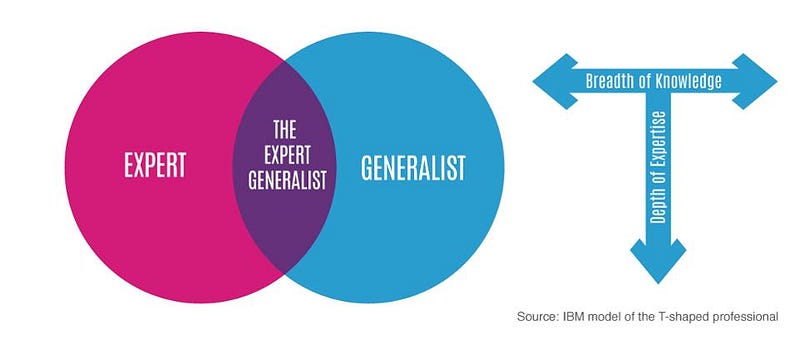

Bill Gates has said of Munger, “He is truly the broadest thinker I have ever encountered. From business principles to economic principles to the design of student dormitories to the design of a catamaran he has no equal… Our longest correspondence was a detailed discussion on the mating habits of naked mole rats and what the human species might learn from them.” Munger has, in short, been the ultimate expert-generalist.

The Rise Of The Expert-Generalist

The rival argument to the 10,000 hour rule is the expert-generalist approach. Orit Gadiesh, chairman of Bain & Co, who coined the term, describes the expert-generalist as:

“Someone who has the ability and curiosity to master and collect expertise in many different disciplines, industries, skills, capabilities, countries, and topics., etc. He or she can then, without necessarily even realizing it, but often by design:

- Draw on that palette of diverse knowledge to recognize patterns and connect the dots across multiple areas.

- Drill deep to focus and perfect the thinking.”

The concept is commonly represented by this model of the “T-shaped individual”:

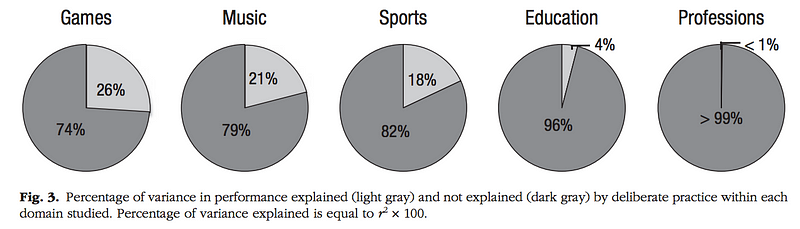

While the 10,000 hour rule works well in areas with defined rules that don’t change such as sports, music, and games, the rules of business constantly and fundamentally change. A 2014 review of 88 previous studies found that “deliberate practice explained 26% of the variance in performance for games, 21% for music, 18% for sports, 4% for education, and less than 1% for professions. We conclude that deliberate practice is important, but not as important as has been argued.” This chart summarizing the results should cause any ardent believer in the 10,000-hour rule to pause:

Being an expert-generalist allows individuals to quickly adapt to change. Research shows that they:

- See the world more accurately and make better predictions of the future because they are not as susceptible to the biases and assumptions prevailing in any given field or community.

- Have more breakthrough ideas, because they pull insights that already work in one area into ones where they haven’t been tried yet.

- Build deeper connections with people who are different than them because of understanding of their perspectives.

- Build more open networks, which allows them to serve as a connector between people in different groups. According to network science research, having an open network is the #1 predictor of career success.

Mental Models: Charlie Munger’s Unique Approach To Being An Expert-Generalist

Developing the habit of mastering the multiple models which underlie reality is the best thing you can do. — Charlie Munger

In connecting the dots across the disciplines, Munger has developed a set of what he calls mental models, which he uses to assess investment opportunities. In fact, he’s identified over 100 of these models that he uses frequently.

What are these models exactly?

The best way to explain is to take the case of one he uses constantly, which he calls Two-Track analysis. It combines insights from psychology, neuroscience and economics about the nature of human behavior. This model instructs that when analyzing any situation in which decision-making by people is involved, which, of course, covers every business situation, he must consider two tracks:

- How they would act if they behaved rationally, according to their true best interests.

- How they would succumb to the pull of a number of irrational psychological biases that seem to be “programmed” into the human brain. Researchers have identified a host of them, and Munger has incorporated twenty-five of them into his Two-Track analysis model.

Another example is classical conditioning developed by Ivan Pavlov in the early 20th century. Pavlov discovered that with the right conditioning, dogs would salivate not just when eating food, but also in anticipation of it when he walked into the laboratory. Munger applies the same logic to business. In his book, he gives the example of how Coca-Cola (one of Berkshire Hathaway’s largest holdings) conditions its customers with the right frequency and type of advertising while using their logo as the trigger.

At its essence, a mental model is a simplified, scaled-down version of some aspect of the world: a schematic of a particular piece of reality. They are deep principles that apply across every area of our life, are always relevant, and provide immediate results by helping you make better decisions.

Munger is not alone in his love of mental models. Many of the most successful entrepreneurs and thinkers in history use some form of mental model thinking:

The better decision maker has at his/her disposal repertoires of possible actions; checklists of things to think about before he acts; and mechanisms to evoke these. — Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon, Author Of Models Of My Life

The quality of our mental models determines how well we function in the natural world. — Billionaire Charles Koch

Principles are concepts that can be applied over and over again in similar circumstances as distinct from narrow answers to specific questions. Every game has principles that successful players master to achieve winning results. So does life. Principles are ways of successfully dealing with the laws of nature or the laws of life. Those who understand more of them and understand them well know how to interact with the world more effectively than those who know fewer of them or know them less well. — Self-Made Billionaire Ray Dalio (Dalio uses the word Principles instead of Mental Models, but he uses it to communicate the same idea.)

How To Actually Use Mental Models Right Now To Be A Better Thinker

The following is a summary of his rules on being an expert-generalist in his own words, excerpted and condensed from the various talks he’s given:

Rule #1: Learn Multiple Models

“The first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models — because if you just have one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models.”

“It’s like the old saying, ‘To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.’ But that’s a perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world.”

Rule #2: Learn Multiple Models From Multiple Disciplines

“And the models have to come from multiple disciplines — because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department.”

Rule #3: Focus On Big Ideas From The Big Disciplines (20% Of Models Create 80% Of The Results)

“You may say, ‘My God, this is already getting way too tough.’ But, fortunately, it isn’t that tough — because 80 or 90 important models will carry about 90% of the freight in making you a worldly-wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy freight.”

This mental model is known as the 80/20 rule. In many situations such as your diet, exercise, friendships, knowledge, and your to do list, 20% of the inputs create 80% of the results. I spent over 100 hours creating the most condensed and in-depth resource in the world on this topic, and you can access is here.

Rule #4: Use A Checklist To Ensure You’re Factoring in the Right Models

“Use a checklist to be sure you get all of the main models.”

“How can smart people be wrong? Well, the answer is that they don’t…take all the main models from psychology and use them as a checklist in reviewing outcomes in complex systems.”

Rule #5: Create Multiple Checklists And Use The Right One For The Situation

“You need a different checklist and different mental models for different companies. I can never make it easy by saying, ‘Here are three things.’ You have to drive it yourself to ingrain it in your head for the rest of your life.”

The Expert-Generalist Approach In Different Fields

Whether or not you decide to follow Munger’s particular approach, one clear takeaway is the value of gaining a wide breadth of knowledge while also drilling deeply into your area of specialty.

Many of the top scientists, business leaders, inventors and artists throughout time have also achieved their breakthrough successes by being an expert-generalist. Albert Einstein was trained in physics, but to formulate his law of general relativity, he taught himself an area of mathematics far removed from his expertise, Riemannian geometry. James Watson and Francis

Crick combined discoveries in X-ray diffraction technology, chemistry, evolutionary theory and computation to solve the puzzle of the double helix. Steve Jobs, of course, drew on insights from his study of calligraphy and a rich understanding of design to create a new breed of computing devices.

Here is an infographic with 25 of the top expert-generalists throughout history:

Click here to enlarge image. Copyright Michael Simmons 2015–2017. All Rights Reserved.

Bain & Company chairman, Orit Gadiesh, attests to the value of being a voracious reader across many domains in her own career, saying:

“Being an expert-generalist has helped Bain see things for our clients that others miss, as we provide unique insights from one industry into another. The approach has differentiated Bain from its competitors.

“I bring into my work everything I do; all of my past consulting projects, all of my readings [100+ books a year]. I read novels. I read about physics, mathematics, history, biographies, art. One reason I work well in Germany is that I’ve read a lot of German literature, German philosophers, German history, etc., even though I’m Israeli. They’re great writers. Likewise, I can work in France because I’ve read their literature. I’ve read Japanese literature, Korean literature, English literature, American literature, Israeli literature, and on and on. I bring all of that somehow into my work. And I think that makes me better at what I do. It also makes life more interesting.”

What’s more, those who can bridge the gaps between silos are becoming more valuable than ever as the amount of knowledge in the world and its fragmentation continue to accelerate.

Being An Expert-Generalist Will Become More And More Valued

The discipline known as scientometrics is the science of science; it studies the evolution of scientific knowledge. Two of the key findings of this field are:

- The amount of academic research is doubling every 9 years

- The number disciplines is growing exponentially.

As disciplines emerge and mature, they develop their own cultures and languages. Each has its own terminology along with its own journals and annual conferences. This specialization has already become so extreme that those who are specialists in one subfield of a discipline often know little to nothing about the work going on in other subfields.

Consider the increasing specialization that has led to one important new area of science, epigenetics. Epigenetics is essentially the study of how environmental factors affect how our genes are expressed. When biology emerged as a field of its own out of medicine and natural history in the 19th century, it would have been possible for any biologist to gain a good grasp of the whole field. Today, many geneticists would tell you they don’t have any real understanding of the findings in epigenetics.

Given this state of affairs, many professionals have determined the best approach is to go into sub, sub, sub specialties, where they can hope to become one of the best if they follow the 10,000 rule. That can indeed be fruitful. But opportunities also abound for those who instead develop an aptitude for building connections across disciplines:

- Expert-generalists face far less competition. The more fields you can pull from, the fewer people you’ll find taking the same approach. When it comes to drilling into one domain, the competition is generally fierce.

- Expert-generalists are able to adapt to change better. Narrowly specializing leaves you vulnerable to the ever-more daunting forces of change. Orit Gadiesh offers insight in this regard: “As technology, globalization, geopolitical challenges, and competition accelerate the disruption of business, people are confronted with challenges, customs, and issues they have never experienced before. I find that experts — someone with deep knowledge limited to just one area — often lack the flexibility needed to adapt to change and can be easily flustered or, worse, be completely derailed.”

- Expert-generalists have more robust knowledge. The fundamental mental models change much less rapidly than domain-specific knowledge. As a result, in 10 or 20 years, they will be just as relevant as they are today, and maybe even more so. This means that you can feel comfortable investing in mental models now, because you know it will pay off in the future.

Curiouser and Curiouser

The business world has placed great emphasis on focus, and rightly so. It is a vital ingredient of success. But more emphasis must now be placed on curiosity. Too often, we are so pressed by the day-to-day demands of work that we aren’t making time for exploration, diving into areas entirely outside our range of experience, letting our minds run, and finding inspiration from encountering new ideas with uncertain payoffs.

So, when you find yourself pushing back, the inner voice of work overload screaming that you don’t have time to be reading that book you just picked up about the physics of time travel or the novel someone recommended by the Nigerian Nobel Prize winner, remember this: Bill Gates recalls that the longest correspondence he’s had with Charlie Munger wasn’t about an investment, it was about the mating habits.

How To Get Started With Mental Models

Convinced about the power of Mental Models? I’ve learned from personal experience that it literally takes years to develop true mastery of these. So, I created two resources for you:

Resource #1: Free Mental Model Course (For Newbies)

If you’re just learning about mental models for the first time, I created a free email course to help you get started. My team and I spent dozens of hours creating it. It includes Charlie Munger’s top mental models, a guide on how to create a checklist based on best practices from medicine and aviation, and a guide that more deeply explains what a mental model is and how to get value from one. Sign up for the free mini-course here >>

Resource #2: Mental Model Of The Month Club

If you are convinced about the power of mental models and want to deliberately go about mastering them, then this is for you. It’s the program I wish I had had when I just getting started with them.

Here’s how it works:

- Every month, you master one new mental model.

- We focus on the most powerful and universal models first.

- We provide you with a condensed and simple Mastery Manual (think Cliff’s Notes) to help you deeply understand the model and integrate it into your life. Each master manual is 50+ pages long and includes:

- A 101 Overview of the mental model (why it’s important, how it works, vocabulary, etc.)

- An Advanced overview that includes a more nuanced explanation.

- Examples of hacks you can immediately use to apply the mental model to every area of your life and career. These hacks are based on my experience and are crowdsourced as well.

- Exercises & templates that you can use on a daily basis to integrate lessons in the manual and get results in your life.

- Facebook community where you can meet other expert-generalists and learn from each other.

All of this for a low monthly price that includes the option to cancel at any time or receive a refund if you’re not satisfied.

To learn more about the program or sign up, visit the Mental Model Of The Month Overview page.

To Become Who You Want To Be, Try These 15 Life Experiments

In short: we now live in a world where anyone from anywhere can quickly learn from the world’s top experts for close to nothing. With affordable tools and trackers, it’s possible to rapidly test that advice to see what actually works. Finally, it’s now easy and free for people to document their stories and share it with millions of others around the world via social media.

As a result, more and more people are doing transformative life experiments, from conquering one fear a day, to learning a new skill rapidly, to even recovering their health when conventional medicine doesn’t work.

Whether you want to call it the Quantified Self movement, or Biohacking, Citizen Science, or simply Self-Experimentation, this personal experimentation revolution is transforming education, personal finance, health, dating, marriage, career growth, art, diet, lifestyle decisions, and much more.

We scoured the web for some of the most interesting self-experiments, and after sifting through hundreds, here are the 15 most inspiring ones that we found…

Want to create your own life-changing self-experiment now? I spent dozens of hours putting together this free mini-course to help you get started.

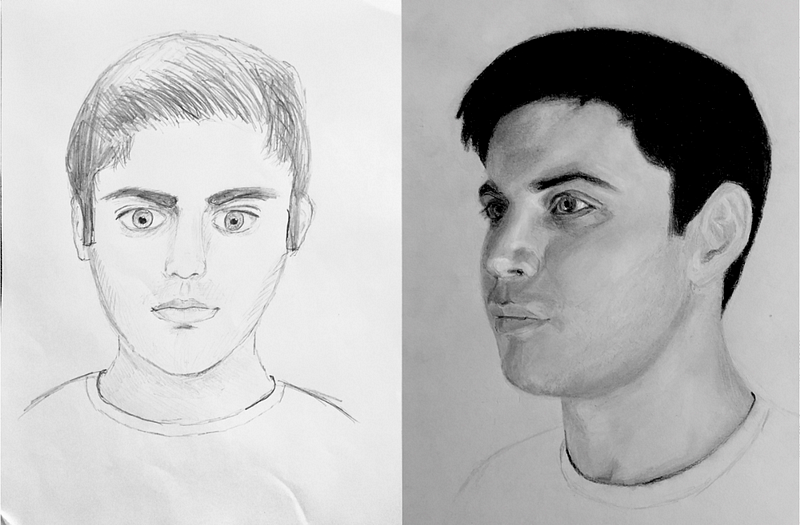

1. Intuit Employee Learns How To Draw A Freakishly Realistic Portrait In 30 Days

Max Deutsch, a product manager at Intuit, is mastering one new skill every month. His December goal was to draw a photorealistic portrait. Here’s the before and after:

Photo credit: Max Deutsch

2. Girl Learns How To Dance Like A Pro In a Year (TIME LAPSE)

Videographer Karen Cheng always wanted to learn how to dance, so she created a challenge for herself: become a great dancer in 365 days while documenting the transformation. The video shows her starting as an awkward dancer, practicing everywhere and everyday, and eventually getting to a place where she can perform publicly. Her day 365 video is truly inspiring!

3. Woman Does One Thing That Completely Scares Her Every Day For 100 Days

Michelle Poler decided to combat her fears head-on by creating ‘100 Days Of Fear.’ Some of her fear-busting experiments included performing at a stand up comedy show, quitting her job, and walking around NYC wearing only a bikini.

4. Guy Plays Table Tennis Every Day for a Year (And Gets A Top 250 Ranking)

Sam Priestley practiced table tennis for a year with the support of a childhood friend / table tennis coach. See how good he got after starting from scratch.

5. Mother And Daughter Lose Weight Together (33kg / 74lbs in 100 Days)

The daughter, 19, suggested to the mother that they lose the weight — together. The mother-daughter duo decided to take on a 100-day challenge, and committed to filming ten seconds of their workouts and healthy eating for over three months.

6. Two Friends Travel To Four Countries To Learn Four Languages In One Year… Without Ever Speaking English

The challenge is to live in four countries, learn four languages and attempt to speak zero English for an entire year. Using Spanish in Spain, Portuguese in Brazil, Mandarin in China and Taiwan, and Korean in Korea.

7. This 12 Year Old Girl Mastered Dubstep Dancing By Just Using Youtube

In 7 months, this 12 year old girl mastered dubstep dancing by just using YouTube. She watched, stopped, applied, and rewinded video clips of the best dubstep music dancers in the world until she mastered specific movements. Wow! I guess I don’t have an excuse to learn dancing now.

8. Man Photographs Himself Meeting A New Stranger Every Day For One Year

Steinar Skipsnes made a resolution in 2016 to meet a new person every day that year. He photographed each encounter and shared them with the world, also sharing the stories of the people he met.

Photo credit: Steinar Skipsnes

9. Young Man Pledges To Get Rejected Everyday For 100 Days

30-Year-Old Jia Jiang had dreams of moving from China to the US to become the next Bill Gates. A few years into his career, he realized that he wasn’t living up to his potential and one of the reasons was because he was afraid. So, he decided to film himself getting rejected for 100 days. Some of my favorite requests: asking to play soccer in a stranger’s backyard, requesting a “burger refill” at a restaurant, and asking to deliver a single pizza for Dominos. He ended the experiences with a transformative set of lessons learned that he has shared on the TED stage and in a book.

10. Personal Finance Guru Puts Her Knowledge To The Test With The ‘One Year No Spending Challenge’

In 2015, Michelle McGagh, a freelance personal finance journalist, pledged to do the impossible: survive a year without spending any money (on anything beyond the bare essentials). Here’s how her year ended up.

11. Procrastinator Commits To Running One Mile Every Day For A Year. What He Learned…

For his 2015 New Year’s Resolution, Derek Salamanca committed to running one mile everyday for the entire year. Derek was sick and tired of putting things off. The experiment proved to himself that he could do something for himself everyday that was a little bit hard, but manageable.

12. A Book Author Writing A Book On Memory Decides To Put What He’s Learning Into Practice. A Year Later, He Became The Memory Champion Of The United States

Journalist Joshua Foer was writing a book on the world’s top memory champions. He decided to take things up a notch and actually experiment with what he was learning to see if anybody could apply the memory hacks. Within a year, he became the memory champion of the United States.

13. How A Semi-Athletic Person Became A Professional Athlete In Only 2 Years

After Michelle Khare moved to Los Angeles during her college to do an internship, she was alone living in a new city. She found a ride group online and started to go there often. Then in two years, she won several races and a collegiate national she got a third place.

14. This Group Of Friends Produced A High-Quality Print Magazine Over One Weekend

“This weekend, a group of San Francisco media friends got together and produced a glossy print magazine, start to finish, in just about 48 hours. The theme was “hustle,” and they got 1,502 submissions from around the world. Their 60-page final product is now for sale online, and you can also preview the magazine’s contents. “Issue Zero” went on sale Monday night for $10, and as of this afternoon, the magazine has sold more than 1,000 copies. Printing costs for each copy are $9, and profits from the $1 markup will be divided in an innovative fashion.” — SFWeekly

15. Once A Year, For The Last 10 Years, This Woman Has Written A Novel In 30 Days

Every year, Kristina participates in NaNoWriMo, an annual writing challenge in which participants attempt to write 50,000 words of a novel in 30 days.

Want to create your own life-changing self-experiment now? Now that you have some inspiration, here’s a link to a free mini-course that I put together on how to be master experimenter.

Why Successful People Spend 10 Hours A Week On “Compound Time”

Warren Buffett, Albert Einstein, Oprah Winfrey all do this one thing outside their to-do-lists everyday.

One question has fascinated me my entire adult life: what causes some people to become world-class leaders, performers, and changemakers, while most others plateau?

I’ve explored the answer to this question by reading thousands of biographies, academic studies, and books across dozens of disciplines. Over time, I’ve noticed a deeper practice of top performers, one so counterintuitive that it’s often overlooked.

One question has fascinated me my entire adult life: what causes some people to become world-class leaders, performers, and changemakers, while most others plateau?

I’ve explored the answer to this question by reading thousands of biographies, academic studies, and books across dozens of disciplines. Over time, I’ve noticed a deeper practice of top performers, one so counterintuitive that it’s often overlooked.

Despite having way more responsibility than anyone else, top performers in the business world often find time to step away from their urgent work, slow down, and invest in activities that have a long-term payoff in greater knowledge, creativity, and energy. As a result, they may achieve less in a day at first, but drastically more over the course of their lives.

I call this compound time because, like compound interest, a small investment now yields surprisingly large returns over time.

Warren Buffett, for example, despite owning companies with hundreds of thousands of employees, isn’t as busy as you are. By his own estimate, he has spent 80 percent of his career reading and thinking.

At the 2016 Daily Journal annual meeting, Charlie Munger, Buffett’s 40-year business partner, shared that the only scheduled item on his calendar one week was getting his haircut and that most of his weeks were similar. This is the opposite of most people who are overwhelmed with short-term deadlines, meetings, and minutiae.

Ben Franklin once wisely said: “An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.” Perhaps the source of Buffett’s true wealth is not just the compounding of his money, but the compounding of his knowledge, which has allowed him to make better decisions. Or as billionaire entrepreneur, investor, and philanthropist Paul Tudor Jones has eloquently said, “Intellectual capital will always trump financial capital.”

To build your own intellectual capital, here are six compound time activities that you can start incorporating into your life immediately:

Hack #1: Keep a journal. It could change your life.

Many top performers go beyond open-ended reflection: they often combine specific prompts with a physical journal.

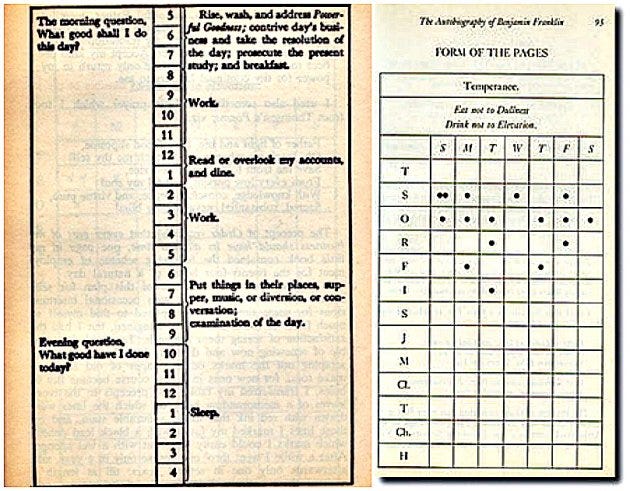

Each morning, Benjamin Franklin asked himself, “What good shall I do this day?” and each evening, “What good have I done today?” Steve Jobs stood at the mirror each day and asked, “If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do?” Both billionaire Jean Paul DeJoria and media maven Arianna Huffington takes a few minutes each morning to count their blessings. Oprah Winfrey does the same: she starts each day with her gratitude journal, noting five things for which she’s thankful.

Billionaire entrepreneur and investor Reid Hoffman asks himself questions about his thinking before bed: What are the kind of key things that might be constraints on a solution, or might be the attributes of a solution? What are the tools or assets I might have? What are the key things that I want to think about? What do I want to solve creatively? Grandmaster chess player and world champion martial artist Josh Waitzkin has a similar process, “My journaling system is based around studying complexity. Reducing the complexity down to what is the most important question. Sleeping on it, and then waking up in the morning first thing and pre-input brainstorming on it. So I’m feeding my unconscious material to work on, releasing it completely, and then opening my mind and riffing on it.”

Whenever legendary management consultant Peter Drucker made a decision, he wrote down what he expected to happen; several months later, he’d compare the results with his expectations. Leonardo da Vinci filled tens of thousands of pages with sketches and musings on his art, inventions, observations, and ideas. Albert Einstein amassed more than 80,000 pages of notes in his lifetime. Former President John Adams kept over 51 journals throughout his life.

Ever notice that after writing about your thoughts, plans, and experiences, you feel clearer and more focused? Researchers call this “writing to learn.” It helps us bring order and meaning to our experiences and becomes a potent tool for knowledge and discovery. It also augments our ability to think about complex topics that have dozens of interrelated parts, while our brain, by itself, can only manage three in any given moment. A review of hundreds of studies on writing to learn showed that it also helps with what’s called metacognitive thinking, which is our awareness of our own thoughts. Metacognition is a key element in performance.

Hack #2: Naps can dramatically increase learning, memory, awareness, creativity, and productivity.

Pulling from the results of more than a decade of experiments, nap researcher Sara Mednick of the University of California, San Diego, boldly states: “With naps of an hour to an hour and a half… you get close to the same benefits in learning consolidation that you would from a full eight hour night’s sleep.” People who study in the morning do about 30% better on an evening test if they’ve had an hour-long nap than if they haven’t.

Albert Einstein broke up his day by returning home from his Princeton office at 1:30 p.m., having lunch, taking a nap, and then waking with a cup of tea to start the afternoon. Thomas Edison napped for up to three hours per day. Winston Churchill considered his late afternoon nap non-negotiable. John F. Kennedy ate his lunch in bed before drawing the curtains for a one- to two-hour nap. Others who swore by daily naps include Leonardo Da Vinci (up to a dozen 10-minute naps a day), Napoleon Bonaparte (before battles), Ronald Reagan (every afternoon), Lyndon B. Johnson (30 minutes a day), John D. Rockefeller (every day after lunch), Margaret Thatcher (one hour a day), Arnold Schwarzenegger (every afternoon), and Bill Clinton (15–60 minutes a day).

Modern science confirms that napping makes us not only more productive, but also more creative. Maybe that’s why greats such as Salvador Dali, chess grandmaster Josh Waitzkin, and Edgar Allen Poe used naps to induce hypnagogia, a state of awareness between sleep and wakefulness that helped them access a deeper level of creativity.

Hack #3: Only 15 minutes of walking per day can work wonders.

Top performers also build exercise into their daily routine. The most common form is walking.

Charles Darwin went on two walks daily: one at noon and one at 4 p.m. After a midday meal, Beethoven embarked on a long, vigorous walk, carrying a pencil and sheets of music paper to record chance musical thoughts. Charles Dickens walked a dozen miles a day and found writing so mentally agitating that he once wrote, “If I couldn’t walk fast and far, I should just explode and perish.” Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche concluded, “It is only ideas gained from walking that have any worth.”

Others who made a habit of walking include Gandhi (took a long walk every day), Jack Dorsey (takes a five-mile walk each morning), Steve Jobs (took a long walk when he had a serious talk), Tory Burch (45 minutes a day), Howard Schultz (walks every morning), Aristotle (gave lectures while walking), neurologist and author Oliver Sacks (walked after lunch), and Winston Churchill (walked every morning upon waking).

Now we have scientific data proving what these geniuses intuited: taking a walk refreshes the mind and body, and increases creativity. It can even extend your life. In one 12-year study of adults over 65, walking for 15 minutes a day reduced mortality by 22%.

Hack #4: Reading is one of the most beneficial activities we can invest in

Here’s an amazing truth: no matter our circumstances, we all have equal access to the favorite learning medium of Bill Gates, the richest person in the world: books.

Top performers in all areas take advantage of this high-powered, low-cost way to learn.

Winston Churchill spent several hours a day reading biographies, history, philosophy, and economics. Likewise, the list of U.S. presidents who loved books is long: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and JFK were all voracious readers. Theodore Roosevelt read one book a day when busy, and two to three a day when he had a free evening.

Other lumineer readers include billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban (three-plus hours a day), billionaire entrepreneur Arthur Blank (two-plus hours a day), billionaire investor David Rubenstein (six books a week), billionaire entrepreneur Dan Gilbert (one to two hours a day), Oprah Winfrey (credits reading for much of her success), Elon Musk (read two books a day when he was younger), Mark Zuckerberg (a book every two weeks), Jeff Bezos (read hundreds of science fiction novels by the time he was 13), and CEO of Disney Bob Iger (gets up every morning at 4:30 a.m. to read).

Reading books improves memory, increases empathy, and de-stresses us, all of which can help us achieve our goals. Books compress a lifetime’s worth of someone’s most impactful knowledge into a format that demands just a few hours of our time. They provide the ultimate ROI.

Interested in reading more? I recorded a webinar to help you to find the time to read and double your return on learning.

Hack #5: Conversation partners lead to surprising breakthroughs

In Powers Of Two: Finding the Essence of Innovation in Creative Pairs, author and essayist, Joshua Shenk, makes the case that the foundation of creativity is social, not individual. The book reviews the academic research on innovation, highlighting creative duos from John Lennon and Paul McCartney to Marie and Pierre Curie to Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

During long daily walks, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky developed a new theory of behavioral economics that won Kahneman the Nobel Prize. J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis shared their work with each other and set aside Mondays to meet at a pub. Francis Crick and James Watson, the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA, batted ideas back and forth relentlessly, both in their shared office and during daily lunches in Cambridge. Crick recalled that if he presented a flawed idea, “Watson would tell me in no uncertain terms this was nonsense, and vice-versa.” Artists Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett took two hours each morning to “do the diary” together: recounting the previous day’s activities in detail.

Many greats made a habit of conversing in large, ritualized groups. Theodore Roosevelt’s “Tennis Cabinet” included friends and diplomats who exercised together daily and debated the issues facing the country. Benjamin Franklin created a “mutual improvement society” called the Junto that gathered each Friday evening to learn from each other. The Vagabonds were a group of four famous friends — Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs — who took road trips each summer: camping, climbing, and “sitting around the campfire discussing their various scientific and business ventures and debating the pressing issues of the day.”

Hack #6: Success is a direct result of the number of experiments you perform

There’s a reason that Jeff Bezos says, “Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day….”

One big winner pays for all of the losing experiments. In a recent SEC filing, he explains why:

“Given a ten percent chance of a 100 times payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you’re still going to be wrong nine times out of ten. We all know that if you swing for the fences, you’re going to strike out a lot, but you’re also going to hit some home runs. The difference between baseball and business, however, is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, every once in awhile, when you step up to the plate, you can score 1,000 runs.”

No matter how much you read and discuss, you’re still going to have to spend some time making your own mistakes. If that discourages you, just remember Thomas Edison. It took him more than 50,000 botched experiments to invent the alkaline storage cell battery, and 9,000 to perfect the light bulb. But at his death, he held nearly 1,100 U.S. patents.

Experiments don’t just happen in the “real” world. Our brain has an incredible ability to simulate reality and explore possibilities at a much faster rate and lower cost. Einstein used thought experiments (imagining himself chasing a light beam through space, for instance) to help construct breakthrough scientific theories; you can use them to set your imagination free on slightly smaller conundrums. The journals of Thomas Edison, Leonardo da Vinci, and other luminaries aren’t just filled with writing, they’re also filled with sketches and mind maps.

Standup comedy is a far cry from inventing, but experimentation is just as key in the arts as it is in science. Take a star comedian like Chris Rock, for instance. Rock prepares for huge shows in venues such as Madison Square Garden by piecing his routine together in small clubs for months on end, trying out new material and getting instant feedback from audiences (they either laugh or they don’t).

Others use experiments to force them to take on new habits or break unhealthy ones. Iconic producer and writer Shonda Rhimes decided to take on her workaholism and extreme introversion and say yes to everything that scared her in an experiment she called the Year of Yes. Jia Jang confronted the universal fear of rejection with his 100 Days of Rejection project, which he then catalogued on YouTube. College grad Megan Gebhart spent the first year of her career taking one person a week out for coffee; she compiled the lessons she learned in a book called 52 Cups of Coffee. Filmmaker Sheena Matheiken wore the same black dress every day for a year as an exercise in sustainability.

As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make, the better.”

Interested in jumping right into becoming a deliberate experimenter? After studying how dozens of the world’s most prolific experimenters have created experimentation engines, we spent dozens of hours creating a free mini-course that includes five email lessons and a webinar to help you be successful with the 10,000-experiment rule. Click here to sign up for the mini-course.

Go Ahead, Take That Hour Now

In a world where everyone is speeding up and cramming their schedule to get ahead, the modern knowledge worker should do the opposite: slow down, work less, learn more, and think long-term.

In a world where frantic work is the focus, top performers should focus deliberately on learning and rest. In a world where artificial intelligence is automating more and more of our work, we should unleash our creativity. Creativity is not unleashed by working more, but by working less.

It’s easy to say to yourself, “Sure! Warren Buffett can do it because… well…. he’s Warren Buffett.” But don’t forget that Warren Buffett has had his learning ritual for his entire career, way before he was the Warren Buffett we know today. He could have easily fallen into the trap of the constant “busy-ness,” but instead, he made three crucial decisions:

- Ruthlessly remove the busy work in order to rise above incessant urgent deadlines, meetings, and minutiae.

- Spend almost all of his time on compound time, things that create the most long-term value.

- Tap dance the work because he leverages his unique strengths and passions.

This lifestyle may not happen for you overnight, but in order to leverage compound time, you first need to believe that a lifestyle where you work less but accomplish more is possible and beneficial; that a lifestyle where you ruthlessly focus on your strengths and passions is not only feasible, but necessary.

To get started, follow the 5-hour rule: for an hour a day, invest in compound time: take that nap, enjoy that walk, read that book, have that conversation. You may doubt yourself, feel guilty or even worry you’re “wasting” time… You’re not! Step away from your to-do list, just for an hour, and invest in your future. This approach has worked for some of the world’s greatest minds. It can work for you, too.

Successful People Are Not Necessarily Smarter. They Just Do More Of This.

This is how you build world-class expertise in any field.

Photo Credit: Frans Peeters

Imagine this…

You’re playing speed chess… with a blindfold… with multiple games going at once.

At the 2015 Sohn conference, the highest-ranked chess player in history, Magnus Carlsen, did exactly this, and it’s a feat to behold.

Carlsen quickly makes his moves (navigating 60,000+ possible chess moves in his mind) while his opponents flounder.

Source: Magnus Carlsen Blind & Timed Chess Simul at the Sohn Conference in NYC

Carlsen’s first win is a checkmate. His second is a resignation. The final opponent loses on time!

If you’re like me, when you see feats like this, you wonder:

How can I perform like this in my own field?

This article answers that question.

You can use the same principle that Carlsen uses to master chess, to master your field and become more successful.

How is that possible? The short answer is chunking. Professor Barbara Oakley, co-instructor of Learning How To Learn — the largest course in the entire world in any subject — has this to say about chunking: “I’m becoming increasingly convinced that ‘chunking’ is the mother of all learning — or at least the fairy godmother… Creating neural patterns — ‘neural chunks’ — underpins the development of all expertise.”

Experts like Carlsen learn how to harness this power through thousands of hours of deliberate practice.

Here’s the full breakdown on why chunking is one of the most important parts to becoming a world-class expert.

Explainer: How Chunking Happens

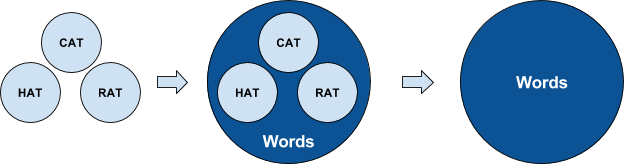

Think about when you first started learning to read (or when you see a child learning to read). Although you didn’t realize it, you were chunking!

The first phase was learning that these random shapes you were seeing were actually a new concept called letters. You combined multiple things into one new thing. That is the essence of chunking. In this case, you combined shapes into a new chunk called letters.

As you developed mastery of letters, you learned that they could be combined into a new concept called words and that these words could be accessed automatically.

Over time, you continued additional levels of chunks. You realized that words could form word groups, which could form clauses, which could form sentences, which could ultimately form stories.

And voila! You suddenly had a new magical ability: the ability to read. You no longer had to sound out each letter. Where there used to be randomness, you now saw order.

When you build more and more complex chunks upon chunks, you gain new abilities. The only reason that reading isn’t considered magical is because so many people can do it. World-class experts, on the other hand, follow the same process, but they just focus on areas of expertise that few other people have mastered and they spend more time in the mastery process.

How Magnus Carlsen Chunks

This takes us back to Magnus Carlsen and his no-longer-magical ability to play blindfolded speed chess.

Carlsen isn’t memorizing each individual piece on each individual square on each chessboard, which would mean memorizing millions of possibilities. That would be truly magical. Instead, he’s using an ability that we all have: the ability to form and use complex chunks. Through years of deliberate practice and chunking, Carlsen:

- Has memorized tens of thousands of complex chunks: still a large number, but much more tenable!

- Is able to automatically and rapidly access those chunks through his intuition.

This explains why he can move fast while his opponents are brooding over where to move next. They haven’t built up enough chunks yet, so they need to consciously examine each possible move and go through all of the implications.

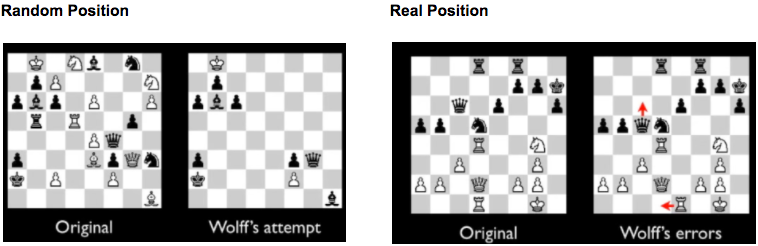

Just how important chunking is was discovered in a landmark study. The researchers had novice and expert participants view a chess position for a few seconds and then reconstruct it from memory.

In the first experiment, the position was one that could appear in a real game, and experts far outperformed novices. In the second experiment, the chessboard was arranged randomly in a way that would never happen in a real game. The grandmasters immediately lost their edge. They could no longer use their saved chunks.

More recently, researcher Daniel Simons replicated the experiment with chess grandmaster Patrick Wolff and posted it on Youtube. Wolff’s attempt in the random position is almost pathetic. In the real position, it is a miracle. Only two pieces are misplaced, and they’re only misplaced by one square.

Also, notice how Wolff describes the feeling when he’s chunking. Rather than describing the process of working with chunks as difficult, mechanical, or deliberate, he describes it as flowing and unconscious. This is a hallmark of mastery.

Chess grandmaster Josh Waitzkin further unpacks what this process feels like in his seminal book, The Art Of Learning:

… over time the intuition learns to integrate more and more principles into a sense of flow. Eventually the foundation is so deeply internalized that it is no longer consciously considered, but is lived.

He later adds…

[A] great pianist or violinist does not think about individual notes, but hits them all perfectly in a virtuoso performance. In fact, thinking about a ‘C’ while playing Beethoven’s 5th Symphony could be a real hitch because the flow might be lost.

What It Means For Us: Why Mastery Takes So Long

Learning the concept of chunking is both exhilarating and disheartening.

It’s exhilarating because it shows us how we can develop superpowers in our field if we stay committed. With just one building block at a time, we become an expert over time.

It’s disheartening because it shows us why building world-class expertise is a process that takes thousands of hours of practice in most fields. Just like a pyramid is built with individual bricks, starting from the foundation and moving up, so too is our expertise. Every chunk is one brick.

In order to learn a single chunk, we must:

- Understand what its building blocks are.

- Understand how they connect into a new concept.

- Practice using the concept so much that it becomes automatic.

Sure, it’s possible to increase the speed at which we build our mental pyramids. Also, some people are hardwired to learn these chunks faster. But either way, if we bypass the process and don’t build a strong foundation, the overall pyramid becomes weaker.

How To Build Chunks In Your Daily Life With The 5-Hour Rule

Dedicating time to chunking is not as hard as it sounds. Simply setting an hour aside per day for deliberate learning compounds over time. I call this the 5-hour rule, and I learned it by observing the deliberate learning rituals of some of the world’s top entrepreneurs.

I may never attain the level of performance of a true prodigy like Carlsen, but because I am building up chunks of expertise every day, I’m able to see my performance constantly improve. Maybe one day, I will be a grandmaster in my field. This is potential that chunking gives us all.

Interested in creating a learning ritual in your life?

I created a free learning how to learn webinar you might like. It’s based on the learning best practices of the world’s top entrepreneurs and performers.

How Elon Musk Learns Faster And Better Than Everyone Else

To explain Musk’s success, others have pointed to his heroic work ethic (he regularly works 85-hour weeks), his ability to set reality-distorting visions for the future, and his incredible resilience.

But all of these felt unsatisfactory to me. Plenty of people have these traits. I wanted to know what he did differently.

As I kept reading dozens of articles, videos, and books about Musk, I noticed a huge piece of the puzzle was missing. Conventional wisdom says that in order to become world-class, we should only focus on one field. Musk breaks that rule. His expertise ranges from rocket science, engineering, physics, and artificial intelligence to solar power and energy.

In a previous article, I call people like Elon Musk “expert-generalists” (a term coined by Orit Gadiesh, chairman of Bain & Company). Expert-generalists study widely in many different fields, understand deeper principles that connect those fields, and then apply the principles to their core specialty.

Based on my review of Musk’s life and the academic literature related to learning and expertise, I’m convinced that we should ALL learn across multiple fields in order to increase our odds of breakthrough success.

The jack of all trades myth

If you’re someone who loves learning in different areas, you’re probably familiar with this well-intentioned advice:

“Grow up. Focus on just one field.”

“Jack of all trades. Master of none.”

The implicit assumption is that if you study in multiple areas, you’ll only learn at a surface level, never gain mastery.

The success of expert-generalists throughout time shows that this is wrong.Learning across multiple fields provides an information advantage (and therefore an innovation advantage) because most people focus on just one field.

For example, if you’re in the tech industry and everyone else is just reading tech publications, but you also know a lot about biology, you have the ability to come up with ideas that almost no one else could. Vice-versa. If you’re in biology, but you you also understand artificial intelligence, you have an information advantage over everyone else who stays siloed.

Despite this basic insight, few people actually learn beyond their industry.

Each new field we learn that is unfamiliar to others in our field gives us the ability to make combinations that they can’t. This is the expert-generalist advantage.

One fascinating study echoes this insight. It examined how the top 59 opera composers of the 20th century mastered their craft. Counter to the conventional narrative that success of top performers can solely be explained by deliberate practice and specialization, the researcher Dean Keith Simonton found the exact opposite: “The compositions of the most successful operatic composers tended to represent a mix of genres…composers were able to avoid the inflexibility of too much expertise(overtraining) by cross-training,” summarizes UPENN researcher Scott Barry Kaufman in a Scientific American article.

Musk’s “learning transfer” superpower

Starting from his early teenage years, Musk would read through two books per day in various disciplines according to his brother, Kimbal Musk. To put that context, if you read one book a month, Musk would read 60 times as many books as you.

At first, Musk’s reading spanned science fiction, philosophy, religion, programming, and biographies of scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs.As he got older, his reading and career interests spread to physics, engineering, product design, business, technology, and energy. This thirst for knowledge allowed him to get exposed to a variety of subjects he had never necessarily learned about in school.

Elon Musk is also good at a very specific type of learning that most others aren’t even aware of — learning transfer.

Learning transfer is taking what we learn in one context and applying it to another. It can be taking a kernel of what we learn in school or in a book and applying it to the “real world.” It can also be taking what we learn in one industry and applying it to another.

This is where Musk shines. Several of his interviews show that he has a unique two-step process for fostering learning transfer.

Side note: Want to take your learning routine to the next level? I created a free learning how to learn webinar you might like.

First, he deconstructs knowledge into fundamental principles

Musk’s answer on a Reddit AMA describes how he does that:

It is important to view knowledge as sort of a semantic tree — make sure you understand the fundamental principles, i.e. the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang onto.

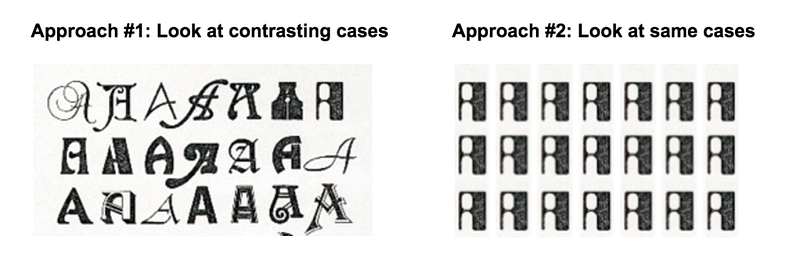

Research suggests that turning your knowledge into deeper, abstract principles facilitates learning transfer. Research also suggests that one technique is particularly powerful for helping people intuit underlying principles. This technique is called, “contrasting cases.”

Here’s how it works: Let’s say you want to deconstruct the letter “A” and understand the deeper principle of what makes an “A” an A. Let’s further say that you have two approaches you could use to do this:

Which approach do you think would work better?

Approach #1. Each different A in Approach #1 gives more insight into what stays the same and what differs between each A. Each A in Approach #2 gives us no insight.

By looking at lots of diverse cases when we learn anything, we begin to intuit what is essential and even craft our own unique combinations.

What does this mean in our day-to-day life? When we’re jumping into a new field, we shouldn’t just take one approach or best practice. We should explore lots of different approaches, deconstruct each one, and then compare and contrast them. This will help us uncover underlying principles.

Next, he reconstructs the fundamental principles in new fields

Step two of Musk’s learning transfer process involves reconstructing the foundational principles he’s learned in artificial intelligence, technology, physics, and engineering into separate fields:

- In aerospace in order to create SpaceX.

- In automotive in order to create Tesla with self-driving features.

- In trains in order to envision the Hyperloop.

- In aviation in order to envision electric aircraft that take off and land vertically.

- In technology in order to envision a neural lace that interfaces your brain.

- In technology in order to help build PayPal.

- In technology in order to co-found OpenAI, a non-profit that limits the probability of negative artificial intelligence futures.