Sharing Stories Through Active Learning, Collaboration, and Publication with Dr. Benjamin Hardy

Dr. Benjamin Hardy is an organizational psychologist and best-selling author. He has published three books, including one co-written with Strategic Coach Dan Sullivan, and is currently in the process of writing three more. Dr. Hardy’s blogs and articles have been featured in Harvard Business Review,The New York Times, Forbes, and many others.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy is an organizational psychologist and best-selling author. He has published three books, including one co-written with Strategic Coach Dan Sullivan, and is currently in the process of writing three more. Dr. Hardy’s blogs and articles have been featured in Harvard Business Review,The New York Times, Forbes, and many others.

He is also a regular contributor for Inc. and Psychology Today and was named the #1 writer in the world on Medium.com from 2015-2018. Dr. Hardy and his wife, Lauren, live in Orlando with their six children.

Here’s a glimpse of what you’ll learn:

- Dr. Benjamin Hardy discusses the beginning of his writing career.

- How Dr. Hardy found time to write consistently, despite a busy schedule.

- The importance of reading and journaling.

- Dr. Hardy’s transition from writing articles to books.

- What are some strategies for moving your career forward?

- Dr. Hardy talks about the online courses he offers.

- Collaboration, co-authorship, and relationship building.

- Learning how to create a distinct voice.

- What are the learning curves for different forms of writing?

- The future of social media, thought leadership, and book writing.

- Trying, failing, and learning from it: teaching yourself to jump on the right waves.

- Dr. Hardy’s top tip: be an active learner.

In this episode…

In a world where digital media is constantly expanding, how do you make your ideas stand out? And if you already know how to set yourself apart and you’re ready to get your thoughts out there, what are the differences between publishing digital content and publishing a book?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy is well-versed in electronic publication, self-publication, and traditional book publication. With three books written, a plethora of published articles, and more books currently in the works, Dr. Hardy knows the best steps for sharing your content with the world—and he’s here to share them with you.

In this episode of The Michael Simmons Show, host Michael Simmons sits down with organizational psychologist and best-selling author, Dr. Benjamin Hardy, to discuss the process of writing, collaboration, and active learning. From teamwork and skill building to sharing work across different media, Dr. Hardy shares stories from his own experience and provides his insight into how you can move your career forward. Stay tuned.

Resources Mentioned in this episode

- Michael Simmons on LinkedIn

- Michael Simmons

- Michael Simmons on Medium

- Dr. Benjamin Hardy on LinkedIn

- Dr. Benjamin Hardy

- Willpower Doesn’t Work: Discover the Hidden Keys to Success by Dr. Benjamin Hardy

- Personality Isn’t Permanent: Break Free from Self-Limiting Beliefs and Rewrite Your Story by Dr. Benjamin Hardy

- Who Not How: The Formula to Achieve Bigger Goals Through Accelerating Teamwork by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy

- Brendon Burchard

- Seth Godin

- Seth Godin’s blog

- Gary Vaynerchuk

- Choose Yourself! by James Altucher

- The Icarus Deception: How High Will You Fly? by Seth Godin

- The Power of Starting Something Stupid by Richie Norton

- Smart Blogger courses

- Jon Morrow on LinkedIn

- Medium

- “8 Things You Should Do Before 8 a.m. to Perform at Your Peak Every Day” by Dr. Benjamin Hardy

- Win Wenger

- Yuval Harari on The Tim Ferriss Show

- Dr. Benjamin Hardy on Youtube

- Niklas Goeke on LinkedIn

- Nicolas Cole on LinkedIn

- Whitney Johnson, Harvard Business Review

- Clayton Christensen

- Dan Sullivan, Strategic Coach

- Richard Paul Evans

- Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson M.D.

- Brian Tracy

- James Clear

- Ryan Holiday

- Tucker Max on LinkedIn

- Jim Collins

- Dr. Benjamin Hardy’s online courses

- Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds by David Goggins

- The Miracle Morning: The Not-So-Obvious Secret Guaranteed to Transform Your Life (Before 8AM) by Hal Elrod

- It’s Not How Good You Are, It’s How Good You Want to Be: The world’s best selling book by Paul Arden

- Smartcuts: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success by Shane Snow

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good Life by Mark Manson

- Substack

- When Violence Is the Answer: Learning How to Do What It Takes When Your Life Is at Stake by Tim Larkin

Sponsor for this episode…

This episode is brought to you by my company, Seminal.

We help you create blockbuster content that rises above the noise, changes the world, and builds your business.

To learn about creating blockbuster content, read my article: Blockbuster: The #1 Mental Model For Writers Who Want To Create High-Quality, Viral Content

Episode Transcript

Intro 0:02

Welcome to The Michael Simmons Show where we help you create blockbuster content that changes the world and builds your business. We dive deep into the habits and hacks of today’s top thought leaders. Now, here’s the show.

Michael Simmons 0:14

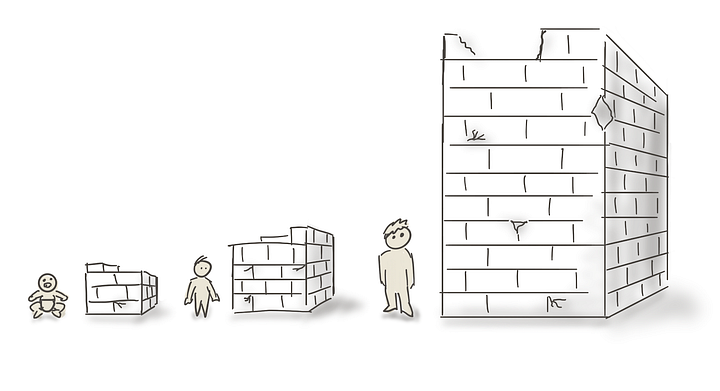

We have an awesome guest today, Benjamin Hardy, I first met Ben, when we were, he was just getting started with writing and getting a little bit of traction. And since then he’s just really blown up all over the place. He’s one at one point, he’s one of the top writers on medium. His writing has been seen over 100 million times, just one of his articles was viewed over 25 million times. He’s written three books. But beyond all of his writing, he’s just a great person. He’s been on several mission trips, he’s fostering three kids, teenagers from impoverished backgrounds, just finished his PhD in psychology. And if that wasn’t enough, that’s when he while he was doing all that he also did all of his writing. So that really comes across in his writing. And one thing I think is really unique about him is his approach to relationship, building and writing, though he’s co authored a few books now and plans to do over 10 co authored books, as well. So we’ll talk about that. And I think it’s really a new model of publishing. And finally, one thing I admire about Ben and we also share with him is just the love of learning. Those not just writing to get clicks, but his writing to make an impact, but also to learn. So he’s writing about topics he wants to learn about, is collaborating with people he can learn from. And I think that’s a really interesting model. So we’ll dive all into that in today’s session. All right, welcome to the podcast. Ben, super, super excited to have you here. And it’s long time overdue. And I want to start off by saying, we first talked in 2016. But I was thinking about it. It’s been a really busy, transformative five years for you hasn’t been

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 2:02

Yeah, the last five years have been crazy for me, obviously finishing PhD. writing books, adopting book five, yeah, five books. Yeah, written quite a few and have a lot more in the pipeline learning kind of how to do it on more the traditional side, but also non traditional side. Yeah, adopted three kids had twins, my wife’s pregnant, she’s literally having another sixth child in like two weeks from when you it’s been a crazy couple years. But it’s been a good couple years. And I’ve enjoyed, I’ve enjoyed our interactions, it has been long overdue, but I’ve enjoyed watching your work. And I also just enjoy kind of where you come from. So it’s good to freaking reconnect with.

Michael Simmons 2:46

Likewise, I appreciate that. And so, you know, I think that story, your story is super fascinating, because we know we have a program where we teach people to write blockbuster articles. And, you know, people are trying to find time in their schedule, or it just takes a while to get progress. How did you, it feels like with your story pretty quickly, you had momentum, your start, you talk more about the beginning of where you were when you started, how old were you? And how did you decide to write? And what happened beginning?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 3:19

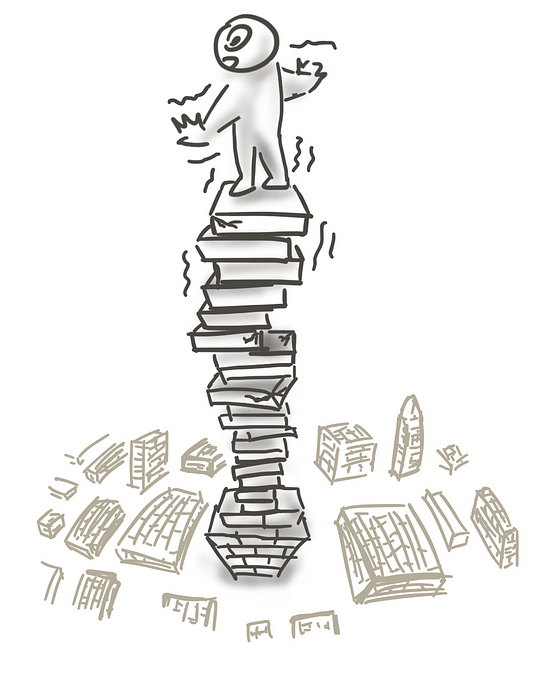

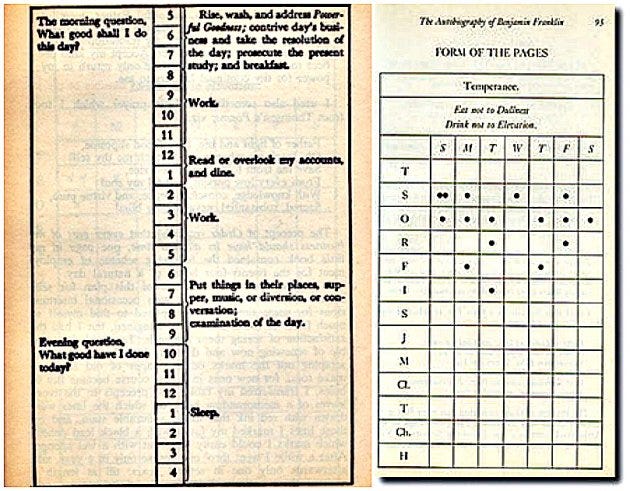

Yeah, so I, I served a church mission from 2008 to 2010. And so when I got back, I was 22. So in 2010, I was 22. Right now I’m 32 10 years later. And I knew through that experience, because I journaled like a madman during those two years, like I learned the value of journaling and and reading books and also just having outside the box experiences serving other people seeing different types of people from different socioeconomic statuses, different cultures, just it was a really eye opening experience for me. And and through that experience, after reading lots of books on that experience, and journaling a lot. I knew that I wanted to be a writer, I didn’t actually know what form of writer, whether I was gonna write like spiritual stuff, whether I was gonna write business stuff. And so from 2010 to 2015, I was studying psychology and kind of just continuing to read a lot of books and continue continuing to journal but I didn’t actually know when I was going to start actually read two really good books that got me that kind of kicked me over the edge. One of them was, Well, probably three books actually in this was in the fall of 2014. And this was right when I started my Ph. D. program at Clemson. But right about that time, I was starting to actually like study marketing, studying people like Brendon Burchard, setting people like Seth Godin and Gary Vee, and I read three books that finally like pushed me one of them was choose yourself by James all teacher, one of them was the the Icarus deception by Seth Godin. And then I read a book called The Power of Starting Something Stupid by a guy named Richie Norton. And I read those three books and I’m finally like, Okay, I’m just gonna start writing online. And I really don’t know how I found it. Actually, I took I took What’s his name? JOHN Morrows. Online Courses guest blogging course this was in early 2015. Cuz I just knew that I needed to like learn how to write headlines and stuff like that. And ultimately, I just found medium.com. I don’t know how I found it. I just started blogging on my own website and just copy pasting into medium calm and applying what I was learning from john morrows. blogging course. Essentially, I probably wrote, like, I probably wrote 40 articles in like, a two month span,

Michael Simmons 5:20

probably. Yeah, it was almost like one article every weekday. Basically,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 5:25

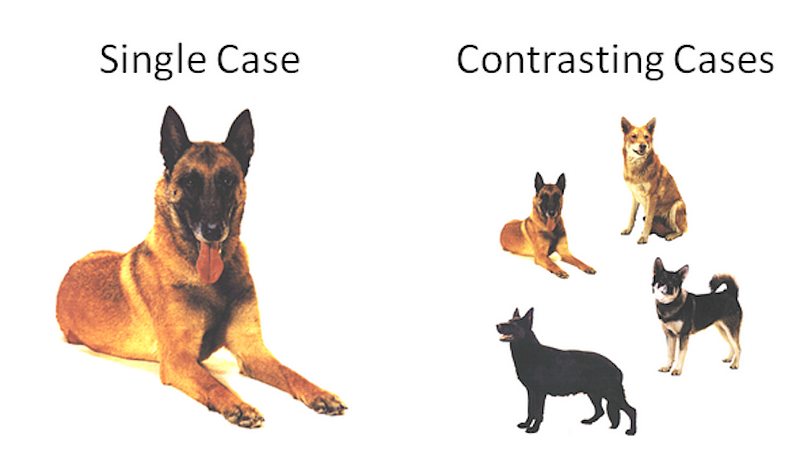

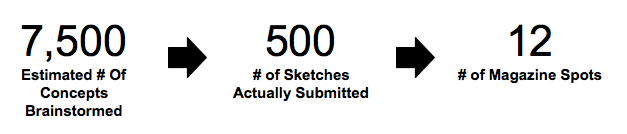

I was writing probably multiple for the first few months, just applying his concepts, because I know you read like hundreds of books over the last like, six or seven years. And so I was just taking his structure, mostly listicles really getting the headlines, pitching them to like low level personal development, blogs, writing them on my own blog. And then actually, he had a contest, he had a contest where whoever wrote the most powerful blog in his perspective, he would share it with his email list. And so I wrote an article called eight things every person should do before 8am. And I published it on medium and I shared it in his contest, I didn’t win, but that article ended up getting viewed like 10 million times. And so where it started, that’s like,

Michael Simmons 6:05

but it’s really funny when the contest, but that’s that’s one when one of your most successful articles, right? I mean, he’s

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 6:10

probably even to this day, because at this point on multiple platforms, it’s probably been read like 25 to 30 million times. But it’s probably my most successful article, even still, to this point. I’m, like, accumulatively, but that that was after about two months of extreme blogging, probably after, like, 40 to 60 articles written, and I was just in a deep low, you know, I was just an extreme.

Michael Simmons 6:35

Let me pause you there. Because already what you’re talking about, you know, a huge outliers. I mean, again, a post that sort by 25 million people. I mean,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 6:44

that’s over five years, that’s not immediate. I mean, that’s

Michael Simmons 6:47

from now five years over every if it’s a lifetime of an article, it gets 25 million. That’s is crazy. And even to go to 40 posts in two months, now that I’m working and teaching other people that’s really exceptional. What do you feel like you had, before you got started committed to writing that made you be able to just be so consistent, even though you were so busy at that time as well?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 7:12

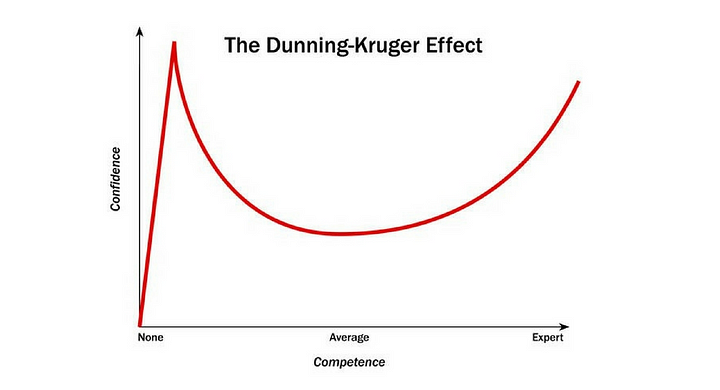

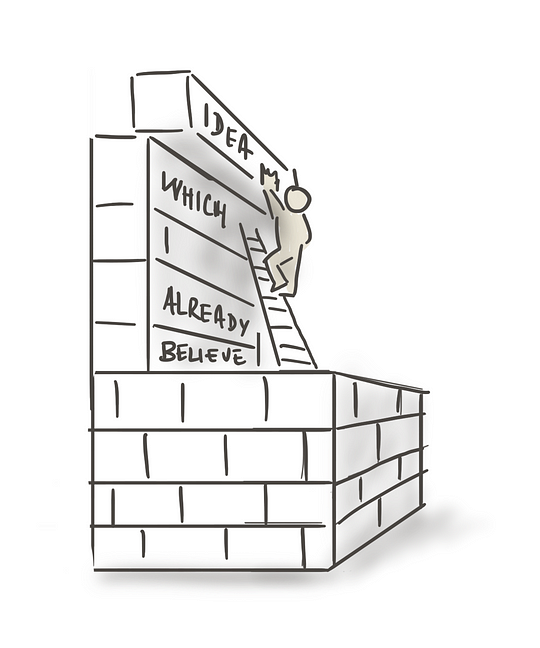

Yeah, I mean, so as a first year PhD student, also, we had, you know, foster kids, which was a brand new experience to us, we’d gotten those foster kids in early 2015. And so I was already in like, an extreme state of flux. Um, I guess what I had was, I had already read so many books, and I’d already journaled for probably 10s of 1000s of hours. And so I kind of already knew how to write in a stream of consciousness way where I didn’t need to overly edit myself, like I just, I was able to just write and I didn’t, most of my articles, especially, even up to this point, or not heavily edited, I just sit down, I really think hard about what’s the concept, and then I get the headline, right, and then I get the structure, right, which is maybe like, three to five sub sections. Once I have that I just literally write in a stream of consciousness way. And I just basically keep it as it is, because that’s kind of how I would flow the conversation. If I was talking to you, I don’t try to overly edit it once I’ve got the structure, right. And so really interesting. So it doesn’t actually take that long for me to write articles. It what it takes is a lot of thought beforehand. And that’s something I did learn from Seth Godin, he says that when he sits down to write, it takes them 20 minutes. But it took him three hours before that to actually get the thinking right, once the thinking is right, and you structure it right. And for me, that’s what my journaling practice is about. So I think I just had, I had a lot of knowledge that was stored in my brain and a lot of experiences. And then I had a way of writing very quickly. And then once I got the structuring down through John Morrow, were just learning how to structure things. I could just experiment, and I had no audience at the time, I had no frame of reference. And I was naive enough to just try a bunch of stuff that was experiments. And so I just threw it out there. Whereas I think when I started succeeding, I started overly calculating my posts, which I think probably actually hurt me.

Michael Simmons 8:58

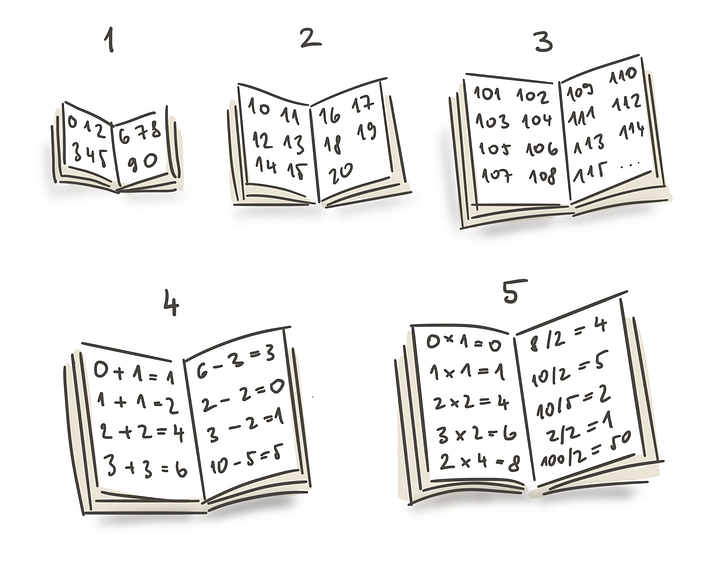

Oh, interesting. Okay, I want to get to that. But before that, this idea of journaling and reading being sort of building blocks to be a better writer, I really resonated with that. I started right reading really heavily when I was 16. How before, and I found that a business together, but we didn’t really know what we were doing. But I was just amazing that it’s been $15 on a book and get all the knowledge that you could do it. And then when I was 18, I went to this course by Win Wenger on creativity. And he his his big thing was you started journaling, I started, I made a commitment for drilling an hour a day, and I basically kept that up for a really, really long, that’s a lot. Yeah, I really don’t do that much. I don’t still do that much. But I write a lot. So maybe if you count if you just probably a lot of my journaling was just replaced by actual writing. I also keep an audio journal now as well.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 9:52

So that’s just interesting that I just keep journals for an hour a day though on my mission. For those two years. I probably averaged an hour. A day of just journaling because I was just writing my experiences. My journals are a lot sketchier now where there’s like pictures, bullets, it in the past, it was just literally like writing my thoughts writing, my experience is very paragraph oriented. And so I probably did journal for an hour a day for well over two years. So I mean, I don’t know. I mean, I never really thought about that much time, but nowadays seems like a lot.

Michael Simmons 10:19

Yeah, I had a similar transition where I went for paragraphs and very formal, right, not formal, but just more formal. And then

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 10:26

now, bullet points. And yeah, now this is like what it looks like. It’s very ugly. Yeah, this

Michael Simmons 10:31

is mine.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 10:32

Yeah, exactly. So my mind and your journaling practice probably has gone through a similar swing.

Michael Simmons 10:37

And, yeah, just for people to I think mapping the journey is really interesting. But don’t I map yours? I’m thinking okay, by 2014. It sounds like you had 1000s of hours of journaling, you know, just in those two hours. You have,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 10:49

yeah, 1000 hours of journaling.

Michael Simmons 10:51

Yeah. And then for right reading, probably, how many books do you think you had read? By the time you started writing? 2014?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 10:58

So I started really reading in 2008, when I left on that mission, and from 2008 to 2014. I probably read

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 11:06

three or 400 books.

Michael Simmons 11:08

Yeah, yeah. So that says a lot to people out there that quote, it takes 10 years to become an overnight success. So if you start your journey from 2014, it just seems crazy. But but in the context, that’s

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 11:20

Oh, yeah. experience, I would say that mission experience was like 10 years of experience compressed into two I you know, on that experience, you don’t have like, you don’t watch TV, you don’t you don’t even really connected, you send one you have like 30 minutes a week to send emails back home, like I didn’t even talk to them except on Christmas and Mother’s Day. And so it’s like, it was just all flow state No, like distraction on phone. I wasn’t a normal college student. We were like, not into the media. I didn’t even know to be honest with you, that the 2008 economic collapse happened like that disconnected from the media. Like I didn’t even know about that until I got home from my mission that like in 2008, the economy crashed. That’s how disconnected I was from like the outside world, even

Michael Simmons 12:00

though I wasn’t Pennsylvania. Well, something this makes me think about is, I recently listened to the Yuval Harari podcast episode with Tim Ferriss. And, you know, he’s famously, you know, has written one of the most popular books in the last 20 years. Like it’s I think it’s like 20 million copies

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 12:15

is that same? Sapiens? Yeah, yeah, 20 million. Hmm,

Michael Simmons 12:19

that’s pretty I can’t remember. It’s all his books are just that one. But yeah, it’s definitely up there. And then the other thing that was interesting is he does these, I think it’s like 30 days per a year, he’s meditating. So when you mentioned being on the retreat, the mission and having all that space, it’s almost seems like it was that kind of space for met, how is that important to you now to have that space for meditation and getting distance and perspective, so you could think better?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 12:46

Yeah, I wish I did more of it. But to me, I look at it now, like recovery, um, as far as like, so my perspective of low is that you’re only trying to accomplish one outcome at a time. So for example, right now, your knee, the one outcome I’m seeking is to connect with you and have a great conversation if I end up trying to create any other outcome, even if that’s just to check my phone. So I can know what the text is like any, anytime you’re seeking to outcomes, your brains pulled in multiple directions, which pulls you out of flow. And so it speeds up your brain. And so for me, I think a lot of it is keeping my brain in kind of more of that alpha state as long as possible. And I think that I kind of lived in that. They say that kids who are under eight years old, basically live in that state, which is why they’re so impressionable. But, yeah, I think I try to live in in this slow of a state as possible, which just means I’m just trying to accomplish one thing at one time. And for me, it makes it easier to be in flow. So yeah, it’s like, as far as if I’m at work, just trying to do this conversation, if I’m trying to write an article trying to do nothing else, unless that are into that article gets done. You know, and I can take recovery breaks when I’m at home, trying to do nothing but being with them. And so, yeah, I think that that mindset just kind of allows for lots of space of emptiness in your brain, and where, for me, I feel like my best ideas happen when actually, if given myself the space to think, then I can, you know, and that’s why it’s just nice to have the journal nearby. And I find that my thinking is really bad. If I don’t give myself that.

Michael Simmons 14:11

Do you give yourself that space with so much busyness?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 14:15

Um, I, I mean, I’ve created systems at this point. Now I have an assistant who basically controls my schedule, I don’t even really read my emails. Um, so part of it’s just the structure at work. Part of it is telling myself I’m not going to work after 2pm and going home and leaving my cell phone as far away as possible, being accountable to my family, telling them that my goal is to keep my phone away from me as much as possible when I’m with them and having my kids know that that’s one of my goals. And just like I guess I’ve just learned as well that like, most things can wait and most things aren’t that urgent, most things that aren’t that important. And so, you know, I’m very clear on my goals. Goal, clarity is really important and also just Only knowing that there’s really only so much you can do in a day. Like if I wake up and I do my two to three major goals that day like I call it a day, like I don’t want you to do 50 things in one day. And you mentioned you stop work at two,

Michael Simmons 15:12

can you talk more about your schedule for the day with writing when it comes to writing?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 15:16

I wish I wrote more man I write a lot of I write in my I don’t write articles very much anymore. I’ve actually tried I’m making made a transition in the last three days to YouTube, which is very experimental right now. But should I still Yeah, I think in the next year, I’ve actually hired someone. So as a forcing function, I apply a concept that I’ve talked about called forcing functions, a lot of it has to do with just setting up situations. So for example, I invest $5,000 a month to work with various video editors. And whether I make the videos or not, it’s gonna cost me five grand and so that Yeah, like, you know, that financial investment, I feel compelled even though I want to do it. So, I do a lot of writing in the form of kind of sketching ideas, I’m actually writing three or four books right now. So rather than writing articles, I mostly do books. And now I’m doing YouTube videos. And so I don’t actually have a daily writing practice, except for journaling at this point. But I now write in spurts. So I like for example, if I’m working on three books, I’m going to spend one week on one where I’m just going to be reading a lot of books, taking a lot of notes on the ideas and hitting that one until I submit it to some deadline to some editor. And then I’ll work on the other one. And it kind of gives me little gaps in between the idea. So right now, my whole writing process is around specific results and specific outcomes. It’s not actually a daily practice just to get blog out there anymore.

Michael Simmons 16:40

Really interesting. You have the other people that I’ve interviewed so far. Nick, Goeke. I can’t remember, if I said his name, right. And then Nicolas Cole each of them very successful writers online, started off in articles 10s of millions of views on their content. And they’re each both reducing the articles and focusing on books. So it’s interesting to hear you say that as well. Yeah. Tell me more about that transition for you. Because you’ve been so successful as an article writer that you have, you’ve already built up the followers. So if you publish things while people are gonna see it.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 17:13

Yeah, it’s interesting. And I’m interested in your writing practice as well. Um, I guess you get to a point of burnout. Like for me, it’s not as fun to write articles. I don’t get the ROI. Except for that I can send them to my email list and just keep fueling my email list because I want to just give them value. Think Do you know who Whitney Johnson is by chance? No, I feel like I’ve heard her name, but I don’t know Whitney Johnson’s awesome. She wrote a book called reinvent yourself. I believe. She’s a heart she writes for Harvard Business Review. She’s She’s a LinkedIn influencer, I think she’s got like 2 million followers on LinkedIn. She’s worked very closely with Clayton Christensen, who is a Harvard Business professor. Anyway, she’s a friend of mine. She’s, she has a book and she talks about basically the S curve. And I don’t know all the steps. But basically, once you once you kind of plateau out or max out on a certain curve, you kind of need to start back over and start the new curve of like a new growth curve. And for me, I wouldn’t I definitely didn’t max out, you know, there’s so much room for improvement that I have as a blogger, but I kind of just maxed out energy wise on it, where I stopped, I stopped growing as much through it, I think I could have still gotten an ROI. But also, the platform that I fell in love with, which was medium changed so much, that there was no value in blogging there. Just because I was getting 1000 email, I was getting 20,000 emails a month for over two years. So my email list, I’ve had over seven, I’ve had over 800,000 people give me their email, just mostly through medium calm. But once that stopped, and once once you get into a different position, where it’s like, now you have to do bigger projects, it stops being valuable to to do those smaller projects, like I don’t know, I don’t know, I just, it’s not as enjoyable as I kind of just have done too many too much of it. I’m not learning anymore when I do it. And also, yeah, I guess it just doesn’t fit my goals anymore. Yeah.

Michael Simmons 19:05

What made books that next? You know, you could have gotten a lot of different paths there. I know, you’ve done two courses before, I think something like that. What made books that next frontier for you, and how does that fit into your goals?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 19:17

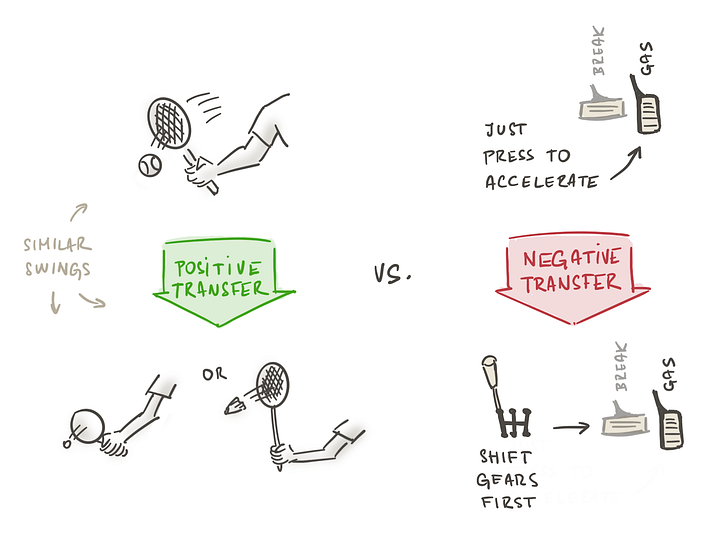

Yeah, so books are fun, because they really push you to learn things differently. So like, for example, I’m writing a book right now on time with Portfolio, which is the publisher that I have written other books with, but that that’s just, it’s just an opportunity for me to do two things think really deep conceptually, and also think really deep as a marketer. You know, because I want to, I want to create a book that could reach millions of people, but I also want to create a book, or an idea that’s totally novel, unique and may be mind blowing. It could be Yeah, I feel like with an article, what I like about actually writing articles and doing online content is you can test that at a small scale, and you don’t have to invest so much into it, but you also don’t get to go And so I’m there. I guess the thing I like about doing online content is it’s micro, it’s experimental. And it’s that fast fail or fast succeed. With a book, it’s just more of a deep work concept. But you know, the whole Cal Newport thing, it forces deep work upon you, because it’s such a big subject matter. The other aspect of books that I like, is that, you know, a book endures whereas an article doesn’t, you know, like, no one’s Yeah, no,

Michael Simmons 20:26

except your 8am article.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 20:28

Yeah, but that article, like, I’m not, no one’s gonna know about that in five years. Um, right, maybe some people but like, um, you know, I’m now doing co-authorship just came out with a book with Dan Sullivan until I saw it. Yeah, we’ll talk about that. So what collaboration is allow me to do is think about different ideas way outside my own genre. I’m co authoring a book with a guy named Richard Paul Evans, who’s a fiction writer, he’s written 41, New York Times bestsellers. And so like, his thinking is so different than mine, Dan Sullivan, 76 years old, he’s been an entrepreneurial coach for a long time, Richard Paul Evans is in his 50s. He’s, like, 20 years older than me. And he’s a fiction writer. And so like I said, one thing I like about doing books, which you could do with businesses or other things is is that you collaborate with thinkers that are so far out your zone, that it creates, you know, unique, unique ideas, unique insights, unique structures. And so I think just books are just a fun vehicle to do that through that I found.

Michael Simmons 21:18

Yeah, really interesting. So can you tell me more about the opportunity that you see in books? So you, obviously, you mentioned the collaboration there that also you get to deep work, but I was just curious that,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 21:32

like on the financial side, or like on a business side, or on a career side, like what do you mean by the opportunity?

Michael Simmons 21:37

Well, just as a maybe, is as a medium, obviously, books have been around for hundreds of years. We’re, we’re in the middle of COVID. So bookstores are closed and self publishing is becoming bigger. And I’ve also seen the rise of, you know, smaller books like yeah, Who Not How is a five hour listen, though?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 21:56

I really liked Oh, yeah, well, and I’m really into books like these. Now. I’m actually like these, like, this is like, you know, Who Moved My Cheese? Obviously a classic, but these hour long reads? You know, even like this one by Brian Tracy. Yeah, like, these little books are freaking awesome. All of these books have sold millions of copies. I mean, even The Art of Work, or like a two hour read, you know? Yeah, I’m really interested in those types of books as well. I think books can lead to a lot of things. Books, if done right can lead to really good positioning, which can lead to future opportunities, or future collaborations, future relationships. And so I think books not only can impact an audience and position you in a certain way, but they can also create future opportunities, it really depends on your goals, you know, like for me, because I really just like learning, like, I don’t know, if everyone should try to write three or four books at a time. Like, it might not make sense. Actually, James Clear, was really smart and doing one book really well. And then just marketing that one book for like, four years now. It’s sold like three or 4 million copies, like, that might be a better strategy than writing 10 books like Ryan Holiday has, you know, like, Who’s to say, but I think Ryan really likes writing. And so he would prefer to just keep cranking out more and more ideas. Whereas I think James is more like, focused on maybe some different results. And so I think a lot of it is is what’s the, what’s your reference frame reference frame? Meaning what’s the outcome? Or what’s the end of that you’re measuring yourself against? Who is it that you’re comparing yourself to, or what is they’re comparing yourself to? For me, I just really like learning. And I like, and so for me, I just, books provide me that opportunity. But they also, they ultimately create a lot of relationships that put me in a situation where I’ll make good money, but also, it’s just kind of sustains my future.

Michael Simmons 23:37

And when you think about that, do you think about yourself as Okay, I’m just gonna be pumping out one book per quarter, just really having amazing collaborations. Okay. You said, No,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 23:48

no, no, they’re all around deadlines. Like, for example, like me and Dan Sullivan have a 10 book contract, not necessarily contract, but essentially, it’s a 10 book deal with Hay House every year for such a big numbers. Yeah, everyone, Tucker Max is the one who set that up. But like, Dan has so much wisdom and ideas, he’s got millions of these little books, and I just get to choose, he’s, I’m the author. And so I get to choose whatever ideas I want, and say, This is the next book we’re going to do. So you know, the next book we’re gonna do with Hay House is going to be called the gap in the game. That’s one of Dan’s old ideas from like, 20 years ago. And so that’s one where it’s just like, you know, I’ll work with Tucker Tucker, Max edits, the books. And that’s just something that I know it’s going to come out next October, it probably needs to be done by March in order for the Hay House to do their thing. So between now and March, I’ll get that book done. Yeah. And then like the other books that I’m doing with Richard Paul Evans, it’s just gonna be according to the timeline of the publisher. But I’m not all about just traditional publishing. I’m actually doing a self published little book like this with Tucker Max and their scribe kind of doing what they call professional publishing because I kind of want to self publish. Yeah, but can only I guess I’m open to all different things. I guess. I’m not lying. I’m gonna do one a quarter. It’s just like, it’s just literally based on like the juggling timelines of these different projects, whatever makes sense to publish first. And you’re talking about this the relationships and those create possibility. And you know, just curious, do you see yourself fundamentally going forward as a writer of a book writer? And

Michael Simmons 25:17

that being your thing? Or do you feel like there’s greater possibilities, and in the future, you might create businesses around it? or? Yeah, so

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 25:25

with the book with Richard Paul Evans, for example, and a lot of people in the in the nonfiction, the business world, the entrepreneurial world, which you and I are in, they wouldn’t know who this guy is, because he’s written mostly fiction books. He’s big into the coaching idea of like, creating, like, you know, he wants to have like a planner, or a journal, or an organizer that’s kind of behind the book. So the book would be kind of the philosophy that would lead people to using the practice, which would be the planner, and then him kind of building. That’s not necessarily an MLM, but like, you know, basically a bunch of sales people who are selling the book, because they want to get people into the organizer. And so there’s a lot of business opportunities behind books that are interesting to me. You know, with Dan Sullivan, I just, I get all the money for the books, he gets all the money for the people who sign up for Strategic Coach. So I don’t necessarily have a business in that, except for just writing books. So I don’t know how I necessarily see myself I already make, you know, I have my own online courses, which, you know, I market regularly and I, that’s where most of my money comes from, okay. But books increasingly provide more financial opportunities. And I may completely pivot in two or three years, you know, I’ll still keep writing books, I imagine, maybe not at this pace. But right now, they’re providing enough opportunities and leading enough people to my courses, which create a great income, that I’m still growing at the economic level that I want to through books.

Michael Simmons 26:50

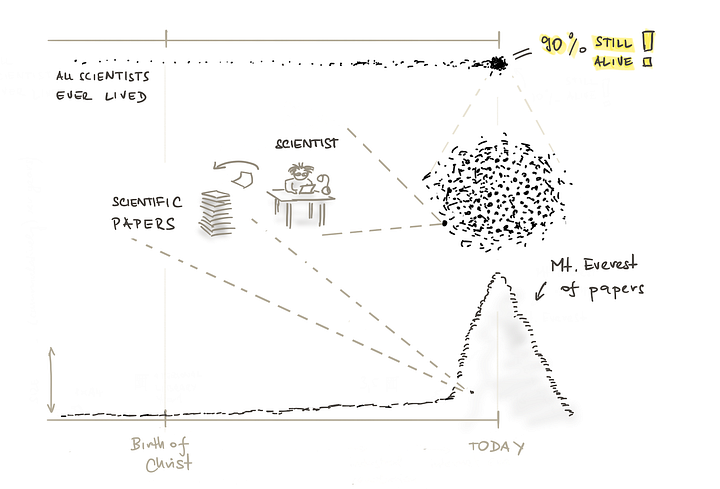

Yeah, even just taking a step back, it’s so fascinating about where we are in the the world of thought leadership, looking at historically, so 20 years ago is awkward to have your photo online, you know, or to take online courses or to date online. Now there’s billions of people creating content, you can do it for free without getting anyone’s permission raise it does well, like your article data, Amazon, it can go to 10s of millions of people at no cost to you. And so there’s so much to leverage from it. And I think a lot about that, a lot of times, it’s easy to forget where we are right now. And that were right in the middle of this tidal wave still. And so that was why I was asking you this question. So it’s interesting to hear how you’re thinking about all the different Yeah,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 27:32

in what’s your current thought process and approach? I mean, everyone’s got a different way of doing it. But what’s what’s kind of what I mean, I know you talked a lot people, but also you’re very strategic as a thinker, like what is it? What’s kind of your view of your own process? Or system or, or strategy moving forward? As it relates to writing?

Michael Simmons 27:48

Yeah, well, similar to I feel like at a fundamental level, you have to do something that makes you come alive. Because if you force yourself into the approach that doesn’t, your writing is not going to be as passionate or curiosity, curiosity. I think whatever you feel, you know, if you’re, if you’re really curious, and like, Oh, my God, this is life changing. And I think readers will feel that or if you’re laughing as you write because you think something so funny, people will, then you know, just put in, I optimise for being like a kid in the candy store. It’s up to you to it’s like,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 28:16

your articles are very that way. Like when I read your stuff, it’s like, this is a deep dive. This was for him, but it gets a lot of joy. You know what I mean? Like, yes, so dense, so long. So you know, like, you don’t care if it takes us 40 minutes or an hour to read, because it’s just like, this is it? You know, I think that’s why your contents done so well.

Michael Simmons 28:35

Yeah. And it’s like, it’s in a weird, it’s like, selfish way. But then it also well, like, it’s like I’m writing for myself, but then it also, it’s kind of on the face that there’s other people like me

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 28:45

as heck, you know, and creative. Yeah.

Michael Simmons 28:48

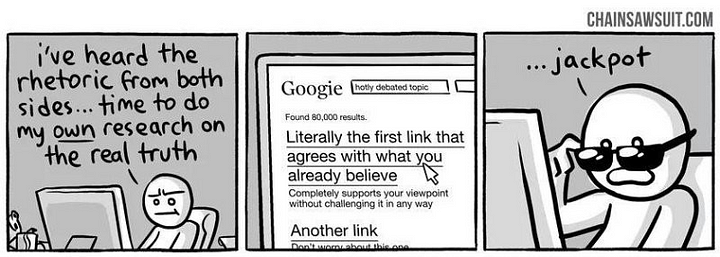

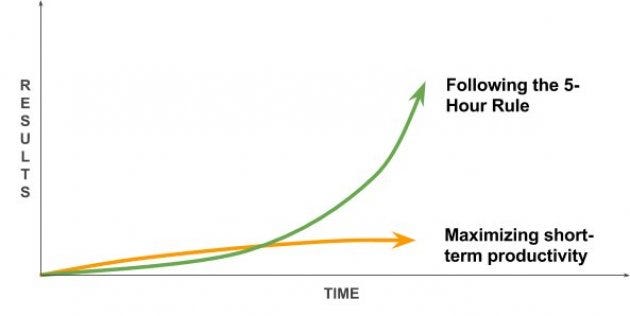

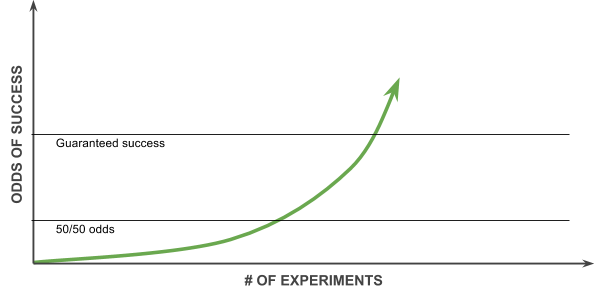

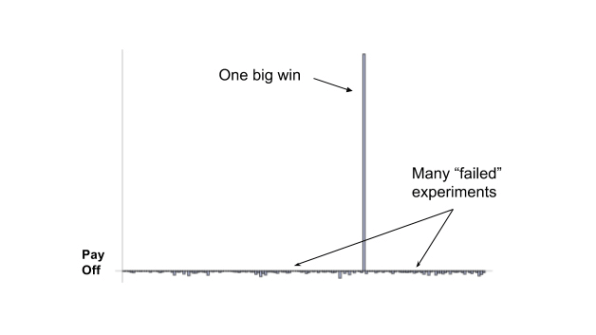

Yeah. And that’s kind of a design decision from that. Like, I feel like I could do more storytelling, and I probably will. But it’s also, I just partially just me wants to just go deeper on the part. And it’s not as exciting for me to go as deep on the story. At this point. Yeah. Although that probably help it. So. And then I also think about it similar to I got this idea from the little bets book. It’s a great book. There’s this idea of consolidated games that Jim, Jim Collins also has this idea of bullets before cannonballs, they do lots of little tests. And then if something really hits, then you double down on it, and then you do cannon balls. And I’m continually surprised, and I embrace this surprise over what resonates with people in your book, Who Not How you kind of talk about this, Dan talks about this with collaboration, that 50% of he comes to something or project that 50% of the idea, but part of the excitement for him is that the other 50% comes through the collaboration. And so I’ve read writing that way as well. So I’m working on a book as well around the five hour rule, but I have confidence investing that time because that’s the So well,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 30:01

that idea. I’ve seen it everywhere man like I, I know you were the one who like wrote the initial blog post, but I’ve seen so many videos on the five hour rule. And I know I remember when you wrote that article. So you’re doing a book on that?

MIchael Simmons 30:13

Yeah, yeah, I’m doing well,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 30:15

I’m excited to see your latest iteration of that.

Michael Simmons 30:18

Thank you. Thank you, I’m excited to say it’s always a little bit nerve wracking going into a new medium, you know, and wanting to get it right. But it’s exciting. And I’ve kind of made a decision also in career to do transformative courses. And so what I mean by that is, we have this writing program, which is pretty high ticket program, where it’s not as much about information, it’s pretty intensive coaching from the team. And it’s a year long program. And it’s all live classes. And everything has costs and benefits. So I feel like the benefit of going with the guy, when I’m talking to Nick, both Nicolas Cole and Nik Goeke, with writing with writing books, they can focus 100% of time on the books, let’s say in writing, they’re out of the day, they’re just writing with creating a course, I’m also spending a lot of time doing coaching calls. And during this way, what I like about that is the feedback loop is I can really see, you just see things you wouldn’t see in writing, when you’re coaching people, that it’s the information, I’ve come to feel like for some people, like if I gave you information, you can apply and get a result quickly. But for most people, they’re just not wired that way to create the habits, and just keep going through all the difficult parts without the coaching.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 31:43

Like coaching as well, you know, I have online courses that involve various aspects of coaching for me, and what are your other I would say, what was that?

Michael Simmons 31:53

What are your online courses?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 31:55

Well, my main one is called Amp, I have several you know, I have actually a 30 Day Future Self course, which is now my basically like my lead generation tool. And it’s also kind of like my what like what Brunson would call your indoctrination funnel. So like, if you went to benjaminhardy.com right now, you could then sign up for free for my 30 Day Future Self course you sign up for it, you’d get 30 emails, and each video, each email leads you to a training, which is like 10 minutes for me. So it’s 30 days of training and pushing. And that one’s free. And my goal is honestly to get a million people through that because I think if I get a million people through that, I could get probably 20 or more 1000 into my year long course, which is called Amp, which is something I’ve been doing for like four years costs $1,000. And then above that a newer program. So it’s like the Amp one, there’s like an Amp platinum, which is like $10,000, more of a coaching program, where there’s like a coaching call group coaching call with me once a month for like three hours. And then there’s accountability laid throughout it. But I liked the coaching. Because it kind of forces me to apply my thought processes, because I’m learning a lot of new stuff, but I’m not pushing it on people kind of like Dan Sullivan, you know, Dan’s thought is that if you’re not testing your ideas on people, especially on check writers, Dan always says test your ideas on check writers. You’re actually testing the validity of your ideas and seeing the feedback you get First off, your ideas aren’t changing fast enough. But second off, who’s to know if your ideas are actually any good. And so I think that it’s good to actually be testing your new processes, your new thoughts on people who want you’re coaching on people who want help on people who are already motivated to change, and you’re learning new insights, and you’re sharing them with them or pushing them through those new lenses, you can then see if it’s actually any good or if it’s valid for people outside yourself. So I think that coaching is valuable for your own thought process.

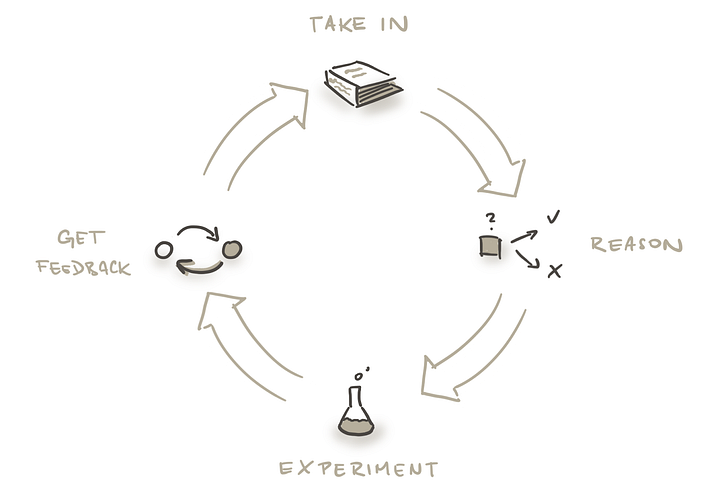

Michael Simmons 33:42

You think about the feedback loops that lead to a book don’t other words, you say there’s coaching calls, articles, what are the different feedback loops, you have to say eventually have something bubble up and say, Okay, wow, this I should focus on?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 33:55

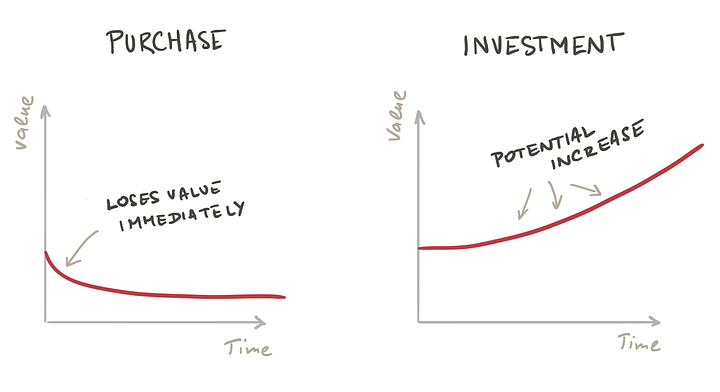

Yeah, that’s a super good question. I don’t know if I’ve actually thought too deep about that. Like, for example, with Who Not How Dan was the feedback loop. You know, he’s been coaching for like 44 years. And that idea became that was a new insight he got that was mind blowing. And everyone you know, he built it as a central concept in his coaching program because of all the feedback he got that this was the most amazing idea. So for me, I just said, Dan, I really like that idea. It resonates with me. I’m seeing that a ton of other people love it. Can I do a book on that? Can I write Yeah, that’s a good one. Yeah, he’s already done all the market research over he did all that and with The Gap in the Game, which is the next book we’re gonna do together that that was the one idea out of all that I learned from him that struck me most I stuck it in personalities and permanent I thought it was so good and I’ve tested it so much in my audience that I’m like, I just liked this idea so much I feel like that’s and and I guess, kind of like the whole bullets before cannonballs. I now I’ll probably view books more like bullets, whereas in the past, I probably viewed them like cannon balls, you know? And sure, like where I used to think articles were bullets in books or cannon balls. I probably now viewed books as bullets. where it’s like, you know, if I throw out, you know, and I’m not just doing it in pure experimentation form, but I’m less attached to the outcome of each book, and I’m getting better and better at launching them. Like, in the past, launching a book was the no deal. Whereas now it’s not that stressful. And also, I’m not as tied to the launch.

Michael Simmons 35:18

Right? That book isn’t gonna be the one book that makes or breaks. You

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 35:23

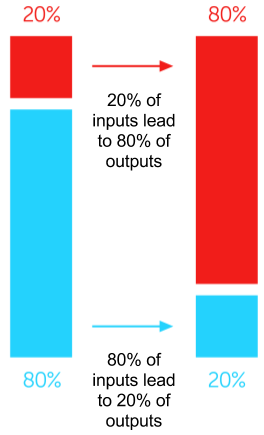

know, Tucker kind of taught me to look at books like annuities. Like it’s like, it’s something that exists long into the future. And, you know, if you keep growing your career, like, it’ll pay you back for the rest of your life. And some books like The 80 20 Rule are going to be, you know, like businesses there, they’re going to be the ones that produce pretty much a percent of your revenue. But some, what I’ve found is, is that you often don’t get to that really good one without burning through one. Yeah. And I’m just not, I’m, I’m not that. I’m okay. If I crank out various books that aren’t that successful.

Michael Simmons 35:55

Yeah, yeah, that’s great mindset, I can feel it’s interesting. When I’m going to this new medium of book writing, I could definitely feel like, I’m putting a lot of pressure on myself to have this one book that does so much better. And that’s definitely really slowing down the process.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 36:08

There’s a lot I love that book, which I know that this is an idea you’ve really solidified. You know, like if you’re really behind that book for let’s just say three to five years, kind of like James Clear with Atomic Habits, that one book could probably take you further than if you just spread between like the last five to eight books like so if you’re really big on this idea, you already know it’s valid. And if you take it further than you’ve taken and President notes could take and then you invest big and spreading it for a few years, that one book could be much of a very successful vehicle to getting you wherever you want to go. So yeah, there’s there’s there is value in approaching it that way.

Michael Simmons 36:43

Yeah. But it’s the same jet. Even though different people have a different consolidated gains model. It’s still theirs. They’re still using the same model like Peter Thiel and Sapiens, what I thought was interesting about those, they started off as course notes, though. I actually just the interview and Yuval Harari, I guess it’s first of all. He was teaching this course on history. And so he created these notes. And then he knows that students were passing them around, and they were almost going viral among students. Then he self published it. And it did, okay. It didn’t really take off. And then there was some ideas started to take off. And then he actually got a publisher. So it was a step by step thing over a period of time

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 37:25

is a very organic, right, yeah,

Michael Simmons 37:26

we’re organic and growing up. So one thing I want to ask you about this unit, how book, it’s an awesome book. It’s one of those books where it’s like, you think you understand the concept. And you’re like, no, like, wow, this is, this is really different. I really resonated with it. And I can see how you really live it. So the fact that you even wrote this book with Dan Sullivan, is proof of that. And I think it’s very unique. So I just my first question, as we segue closer to the book is, on the one hand, I was kind of surprised of my before I read the book at just know, okay, Dan has written four books. They’ve been some of them have been very successful. He’s great momentum. Why is he going to write a book with someone else? Dan Sullivan’s amazing. He’s built an amazing business. There’s a lot of wisdom. But you have enough of an audience and all that. And you know how to do the research, you could do it on your own and have your own idea. What made that? What did you see that no one else did? And how does that relate to your book?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 38:27

Like as far as doing a collaboration with Dan? Yeah, yeah. Um, well, so Dan is really well known and really well respected in a very small pocket. You know, there’s a small pocket of probably 20 to 50,000 people who freaking respect everything he says, and, and so I just had gotten immersed in that pocket. And I just, I had been learning from Dan since about 2015. And was applying his ideas, which helped me, you know, as a graduate student, essentially build a seven figure business. And so I just really liked him. I liked his ideas. And once I heard the Who Not How concept, and I’d actually been wanting to do co-authorships, just not not necessarily to tap into other people’s audiences. I just, I just want connections with various types of people. And I’ve been thinking about co-authoring opportunities for like, maybe a year before that, that came to be

Michael Simmons 39:27

Can I pause you there?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 39:28

Yeah, please. Yeah.

Michael Simmons 39:29

So you know, I really appreciate connection with other people as well. And so I feel like the approach I would have taken maybe it would be, you know, you have your deep enough in that pocket, you know, people where you could, you could interview him or do an interview series or write them long articles, but to commit to a 10 book deal, although you probably don’t have to do all the time, but to even commit to one book. That’s a really big commitment. What made you want to collaborate with someone at that level?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 39:55

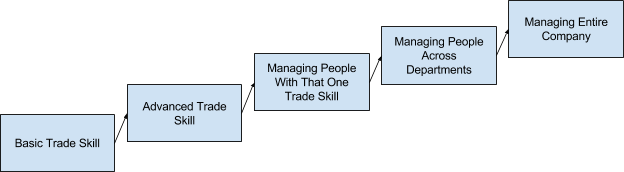

Yeah, so it definitely was not initially a 10 book deal. Initially, it was just I wanted to do a book with him because I felt like, you know, from my perspective at the time, which is when I initiate that beginning, which is back in like 2018. I wasn’t thinking big picture, like I was thinking, if I do one book with Dan Sullivan, first off, you know, I’ll probably get 250 grand for the book, which would be great. I know that I could probably crank out a really good book in three or four months, it’s not going to take too much of my time, but I’m going to learn a lot. And I really initiated that project, because I was getting more serious about becoming an entrepreneur. And I just felt like if I was going to write that book, it was forced me to learn and apply the principles in it. Right. So learning, that was the learning curve I personally wanted to go through was learning and I felt like if I was gonna write a book with Dan Sullivan, I would get direct access, and be able to add 20 on his best ideas, which, you know, people join Strategic Coach where they’re paying 20 grand a year for, I felt like if I join, if I wrote this book was in first off, it would force me to learn how to be a better entrepreneur, but I would also be able to at 20 his ideas. And so that was kind of my mindset, plus, I knew I would make enough money on the book, at least from that standpoint, to make it worth it as far as my time investment. And I also just thought, given his audience, given my audience, it will do good enough that it will be justifiable, like the success of the book will be successful enough that it would have been worth doing anyways. Yeah, so what I hear you saying at some level, is that you’re really throughout the process, putting a really, really high value on the learning that you’re not just trying to 100 capitalize on your existing success, but that you feel like long term learning is really important. He talked about how you see what makes you value so highly. In that sense, then, yeah, learning for me is like probably 80% or more of my motivation, because if I can actually learn something, I can apply it long term. So like, for example, with Who Not How has an idea when I first started writing, Who Not How I just had it myself and a single assistant, and I was probably in more of the identity of a writer. Whereas I wanted to kind of make the transition to being a bigger picture thinker. I wouldn’t say I was looking to become an entrepreneur, as far as an identity level, but I wanted to actually have that be a part of my skill set and knowledge be good at that. And so, you know, through the process of writing the book, I went from zero to like, having six, you know, employees and, and learning to basically get who’s to handle most of the house that were ultimately distracting me. And so I felt like it was a good learning curve for me to learn how to be a better leader to having more flow. And so I just, for me, learning creates opportunities. And so I do things to learn, because I know that I’ll be able to be at a different level as a human being to create different outcomes. So I knew that in writing that book, I would learn how to be an entrepreneur and learn how to be better with my time. And honestly, if I hadn’t learned how to do that, I wouldn’t be able to do four books at a time right now, I’d still be doing one book at a time. But because of the principles, I learned through writing that one book, not only now my position differently among pretty cool community, but I now have the skills to do more of what I really want to do, which is learning right? Hmm, wow, I wouldn’t be able to do four books right now, if I wasn’t applying Who Not How

Michael Simmons 43:12

was interesting, five years ago, before I was writing my own name, I was, I had more of an agency, I was working with different people. And one of the clients, his business was around 1.5 million, this year, they’re gonna be doing 50 million. And Holy cow, it’s just really growing. Yeah, and I learned so much. So part of this part of the thing, writing it, I really did go through all this material, and is really try to, when you write something, I call the explanation effect, that when you write something, you just learned so much of a deeper level of accountability behind it. So it’s really interesting that I think I can see

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 43:49

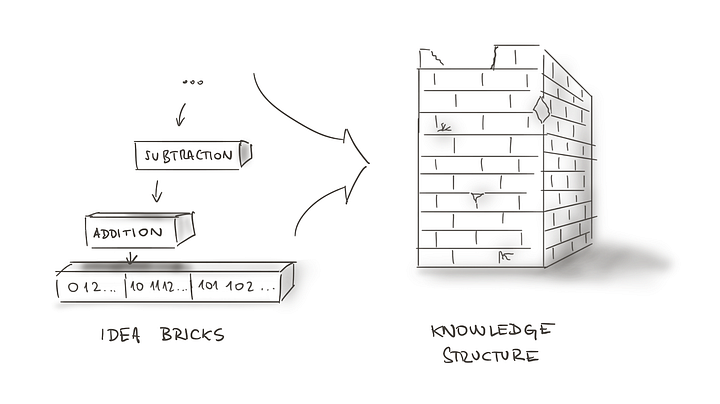

the things I love most about writing is it forces you to be able to explain it? And if you you know, I think I think I understand that if you can’t explain something you don’t know it. And so I think part of really deep learning, and journaling, hashing and then turning into something that’s comprehensible to someone else. And I think part of that editing, you know, I think it’s not all just you and your head getting it, right. But it’s like you going back and forth with an editor, you’re learning how to explain it to other people, it forces you to know something deeper than maybe, you know, I mean, to me, that’s why I really enjoy writing is because it actually forces you to be able to teach it to other people and explain it so that you actually know what you’re saying. Likewise,

Michael Simmons 44:28

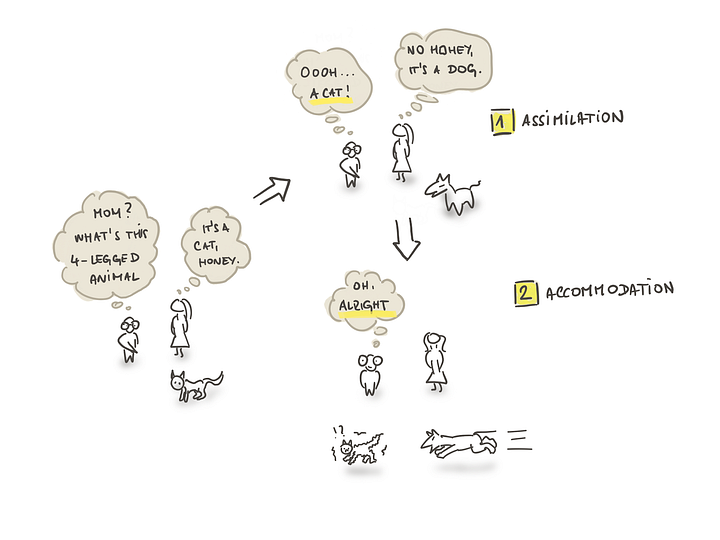

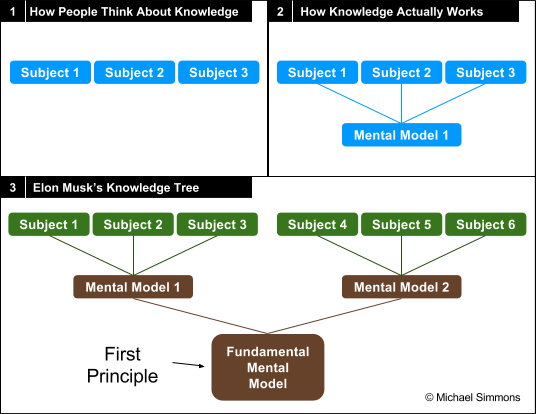

I think about it as a pyramid, that and it like it goes from the least formal at the top where you’re just journaling to yourself, or you could be speaking out loud, that’s as a benefit. Then there’s a line you cross as you go down the pyramid, where you’re actually talking to other people, and it’s informal, like I guess we’re talking to you and explaining an idea. And then at the highest level, is when you’re getting paid to teach someone and you’re doing multiple edits. It just gets a deeper level of learning. But I don’t think people appreciate the value, the exponential change that happens in learning When you go from just explaining an idea and formally to, if you’re writing a book on something, you really and you’re doing the editing, it’s not just the writing and explaining it, it’s also the editing. Can you talk more about that is, where do you see the role of editing and your own learning process?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 45:17

I think editing is think editing is where you kind of crystalize it, you turn it into structure, a lot of learning is just, you know, broad, ambiguous, you’re learning ideas, but you don’t actually comprehend it as far as like turning into a system steps or structure. And I think that’s where editing comes in, is having to turn into something that’s clickable, something that can be used something that actually has steps, you know, you have to take the material and turn it into material, essentially. And so I think that editing is just the process of knowing what to leave out knowing what to leave in learning the structure, the way to say it. And so editing is what turns it into, into knowledge. I think before that, or maybe editing is what turns it into, like applied knowledge, or Intel, or wisdom or intelligence before that it’s just broad and useful information. Maybe it goes from information to knowledge, through editing, right information to knowledge, I could see it helps make it concrete, like you said, and also the connections between the knowledge, which is probably just as important as the understand the bits of knowledge themselves. But if you’re really digging into something like for example, connecting to ideas with who and I, one of the ideas is that if you’re always doing the how, and let’s just say you’re doing 10 different houses, I’ll connect that to the idea of psychology of decision, you know, and if you know, decision fatigue, meaning if you have too many things on your mind, you’re burning out your willpower. And so I think through the editing process, you can think about a set of ideas, and then you can step back and connect them to a different set of ideas, and then pull it together so that it now is a new idea that makes a lot more sense. And so I think that the funnest part for me in writing a book is actually not the initial hash, that’s the hardest part because it’s just throwing out junk, essentially, for me, it’s really fun to get going through it, and then to pull new ideas in or to, you know, to actually connect the dots. And that’s, I think, what editing is, is connecting the dots, but also making it comprehensible. And to me, that’s, that’s the funnest part. Really well

Michael Simmons 47:15

said. The other thing that I thought was really interesting in your approach, and I loved it is back when I had the agency, I really realized that ghost writing is actually harder than writing under your own name, because you have to learn someone’s voice and their stories and things like that. And so she’s you’re, you’re already know yours. But what you did, which is really awesome is the book is under your own voice. It’s your alley, pulling your own stories, and then you’re pulling with Dan’s work, and it just felt really integrated. It felt authentic, the way cuz ghost writing feels authentic. And you can just see that you each got what you wanted out of it. And I love the interviews, pull it from David Goggins way, his book where you have on the audio version, you have the interviews, you’re interviewing him after every chapter about that chapter and the thought,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 48:03

yeah, yeah, that was that, that that was Tucker’s idea. Tucker, Tucker’s company published David Goggins book, I don’t know where the original ideas I think David’s book is the first one that did that. I know that Jim quicks book did that as well. But yeah, Tucker just talks to Hay House about it. Hay House was the publisher. And they just said, We want you to interview Dan between the chapters. And so when we record the audio book, it was actually even before I read the audio, but basically, I had two hours with Ben and I just had to like, look at the manuscript and make sure I knew it was in the chapter. And I would just basically give him a jumping off point. Hey, Dan, in chapter one, we talked about this idea, and then he would just talk, once we finish the conversation. Alright, Dan, and Jeff to talk about this idea. Tell us about it. And then after we did our two hours of interviews, then I went and actually read the audio book. Um, but yeah, that was, that was all Tucker’s idea. But also,

Michael Simmons 48:50

how about the ghost? idea there? I have never seen Well, yeah.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 48:53

Yeah. As far as writing the book, that was the thing that was the major decision to make was, whose voice Are we going to put this in? And that was the hardest thing to start with. Because I didn’t want to write in Dan’s voice. And Dan would certainly not want me to speak for him. And so once we just kind of, because Who Not How is a great idea as far as let the who do the How? That just allowed me to say, Well, I’m the who. So I’m just going to write this book. I’m Ben Hardy. This is actually my book. And I think it came from the idea that Dan actually told me and Tucker told me that I’m responsible for the content of the book. Dan has no responsibility over the book. He trusts his who. And so I had to face the bold realization that I actually get to determine every aspect of this book. Dan has no say he actually hired me as his writer to actually write the book, and it’s actually my book, but he’s the primary author. And so I think that realization just made it took me time to realize it is is that I can make this book whatever I want to, and so I’m just gonna write a Benjamin Hardy book with Dan Sullivan’s name on it and and you know, I’m pulling a lot of his ideas. So he’s, so he gets some responsibility. But it just became the only way to write it. To be honest with you with the other book that I’m co authoring right now with with Richard Paul Evans, this is actually the current problem of that book is whose voices that in? Cuz I find that co authored books where they say we do Yeah. You know what I mean? It doesn’t feel very good. And so you almost have to say whose voices is thin? And how are you framing both authors, whereas with Dan’s books, it’s now very easy. I’m established as his writer, I get to just choose what I say it’s actually a Benjamin hardy book, but I’m just pulling from Dan Sullivan’s ideas. Yeah, it’s honestly,

Michael Simmons 50:37

it’s such a big innovation.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 50:39

Because it was unique, right? Yeah,

Michael Simmons 50:41

it’s a really big innovation, because there’s so many smart people in the world, like Dan, where he has these ideas. And they’re known in a small pocket, but they should be more widely known. And it’s, it’s harder, it’s probably not as it probably wouldn’t be as fun for you to write the book under ghosts, if it was gross written that way. And you probably wouldn’t mind having to take the

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 51:01

ownership over it.

Michael Simmons 51:03

Yeah. And then for him, if he does, it’s, it’s, I’ve had, I’ve tested trying to have people write parts of the article that I did, and it just never worked and just create more work for them, then it creates more work for me to edit there, I have to rewrite the whole thing. So I can see, I think the good part is, is that

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 51:21

Dan doesn’t care what the book is, he only cares that it’s a good book. And that’s why he just trusts the who. And also the book is a tool for Dan. Yes, he hopes that people learn these ideas, because they’re ideas that he’s been polishing and refining and, you know, learning for 40 years. So obviously, he hopes that the book serves a broader audience. And then something that that’s obviously my job to do. But primarily for him, that book is a tool to get people into Strategic Coach. And so one thing that as a creator, or as just a human being, you have to remove your ego is is that he can’t tell me how to do the book, because he himself doesn’t have the skills or the knowledge to produce knowledge that’s broad, whereas that’s a skill set that I’ve developed over the last five years is taking ideas and making them interesting to big groups of people. He knows he doesn’t have that skill. And, and so what’s great about him, and also just the idea of not how is that he wouldn’t advise me how to write the book. And he also acknowledges that maybe the book is a book that he himself doesn’t even like, but he knows that it’s positioned to hit people. You know, and, and so far, I think part of that type of creativity is knowing your role, knowing their role, and knowing that your way of doing it isn’t the correct way. And I think that’s what I like about Dan is that he, he just stepped aside, and he said, I don’t know what this book is going to be. But I don’t care, because I trust that Ben and Tucker know what it should be. And even if it’s not the book, I would have written or even known how to write or even like, it has a job, it has a purpose. And so I’m just gonna stay out of my way on that. And I think a lot of people they’re too ego egotistical, and they want to control the process or control what it says or it has to say this or that. And those things get added those things get in the way of it being effective. Yeah,

Michael Simmons 53:08

it really honestly, it was a confronting book in the most positive way you want every book to confront your existing beliefs, because I really value learning. And so I was always taking those that I’ve been focusing a lot on the how of it. And I could see how late let’s say he had practice writing Well, okay, taking a step back here. So, one thing I’ve thought about with delegation are other things that if you know how to do something, it’s easier to recruit people and to manage the process, because then you could tell what quality is. So, but it’s also he doesn’t

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 53:43

believe in delegation.

Michael Simmons 53:45

Yeah. So yeah. Tell me more about that. He, you know,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 53:48

he doesn’t go ahead. Go ahead. Go ahead. Yeah, that

Michael Simmons 53:53

now I could see how to disadvantage in a way if you know too much about it, because you’re gonna want to, if you knew something about writing, but it wasn’t the best, you’d want to jump in and try to get everything. And it just wouldn’t have been as good as if you just giving you the freedom and almost just really partnering?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 54:07

Yeah, I mean, he doesn’t believe in delegation, because he, first off, he doesn’t believe he knows everything. He believes that other people have skill sets and knowledge outside of him. And, and so rather than hiring someone that needs to be trained, he just hired someone or teams with someone who already can get the result, you know, and so he doesn’t, there’s no training or transfer of knowledge that needs to be done. He just has a goal. And he aligns that goal with the person who can accomplish that goal, rather than him having any need or have knowledge about how to do it. He’s just like, yeah, we want a major book. It You know, I’m, he doesn’t need to know the how it’s kind of like you don’t need to know, you know, you don’t need to sit over the mechanic and tell them how to fix your car. Like, I’m okay not knowing how the mechanic fixes my car. All I want is a sweet car. And so yeah, he doesn’t Leaving delegation at all he believes in teamwork. And he believes in teaming with people who already know how to who already have the skills and capabilities to produce the result. And he just sets things in motion, he does what he does, which for him is creating ideas, testing them on his audience, coaching his audience. And then from there, there’s a ton of different outcomes that are occurring, that he has no clue how they’re getting done, you just teamed with people who know how to do those things. For example, podcast, he just hired someone who is really good at creating podcasts. And then he just lets them do their result. He just steps out of it. So yeah, I think that the idea of delegating is passing a task that you don’t want to do or that you see is beneath you down to someone else, whereas he sees it, as you know, teaming with someone who has amazing skills and abilities that he doesn’t have. And so it’s just it, he looks at people not down on them, he looks up to them, that he’s teaming with people who are amazing, even his employees who are answering his emails, he sees that is an amazing teamwork, not as a delegation. Yeah, it’s a fundamentally different way of looking at it. And so now you have people who values people as unique rather than as cogs.

Michael Simmons 56:09

It’s almost like the Warren Buffett’s idea of circle of competence, where you stay inside your competence. And then other people, you buy other people to be a nurse, it’s that apply to

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 56:19

that unique ability. He just said, I’m gonna stay right here, because this is where I want to be. And this is where I thrive. You stay over there, I’ll stay over here. And then he just finds who’s for everything else. And he chooses that he chooses where he wants to stay.

Michael Simmons 56:31

And for you, how are you thinking about the future? Now? You have now have one of these under your belt, you have the option to do nine other books with him. Alright, are you do you think you’re going to try to do one of these per year or just

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 56:44

do more? Well, it stops making sense to me. So I already know the next two I want to write I’ll write The Gap in the Game and I’ll write a book called 10x is Easier than 2x, which is another one of his ideas that I just read him. Yeah, yeah. And so we’re already you know, Tucker’s can talk to Tracy, the CEO now that the book crushed it, the book actually sold 90,000 copies last week. Last week, we actually want to make a we broke a Hay House record. Yeah.

Michael Simmons 57:09

That’s pretty good. I

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 57:09

did a I did a contest with the ebook, because ebook was 99 cents, and I did a contest. And so it led to 73,000, ebook sales, which was really unexpected. But um, one thing I’m doing differently with the gap in the game is I’m hiring Tucker max his team to actually write the book. So this is something I’ve never done before. I wrote all tonight, how Tucker edited it, the gap in the game, I’m actually going to let his team write it. And I’m going to be the editor, and then I’ll let Tucker edit me. But I’ll do interviews, I’ll go through their process of basically telling them the ideas, and then I’ll let them write it, and then I’ll edit it. And so it’s going to take me a lot less time, it’s gonna be different cuz I’ve never done a book that way.

Michael Simmons 57:48

Wow. So you’re also becoming a publisher then?

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 57:50

Yeah, but I My name is on and I’m, you know, I’m almost more like a project manager of sorts, but project creator and manager. But that’s not all the books me and me. And, for example, me and Richard Paul Evans are just going to co write that book. And yeah, oh, but with with the Dan books. You know, I’ll do those two next. And I’ll just see where I’m at. I don’t know where I’ll be in two years, I don’t know where my life will be. I don’t know where I’ll be with my kids. I don’t even you know, I might, I might need a huge hit. So we’ll just yeah, we’re at, we’ll just see, I but I do want to do those next few books, because those two are interesting enough. And now each book will come out every October. So next October, Gap in Game come out into October from now, 10x is Easier Than 2x.

Michael Simmons 58:30

Yeah. And so, you know, one thing I think about is, in a way, we’re in a very real war for attention, that attention is a limited resource. There’s literally companies spending 10s of billions of dollars, mastering the skill of capturing attention and countries, you know, really well just, you know, mimicking organic social media and getting attention. And so, if you’re a thought leader or writer, you’re, you’re operating in that environment, you know, you know, although, you know, we don’t think of as a war, but, you know, that’s just the environment. And that’s, there’s a huge amount of people, I there’s something called Zuckerberg law, that the amount of social media content is doubling every year. I’m not sure, I believe. So, you’re planning to do this, you know, sounds like for the rest of your career in some way, shape, or form. So I was curious, what do you feel like is your edge or advantage over the long run? Like for I’ll just give an example. For me, I feel like it’s the research that, let’s say, if I wanted to write a book about, I couldn’t write a book about dentistry right now, because I’d have to spend hundreds or 1000s of hours have to learn it. And so I view myself similarly is building up this huge pool of knowledge that gives me the ability to write a lot about different things that other people couldn’t even write about. Unless they did a huge amount of research. But that’s just yeah,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 59:49

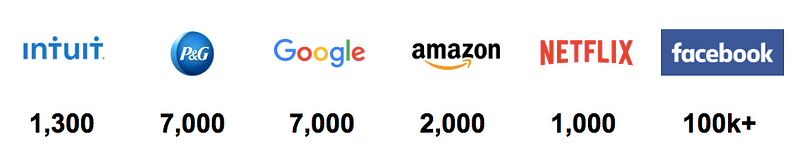

I think my edge is actually interestingly becoming more Who Not How you know, so like, I do have the skills and the desire to research and To package and to teach, I guess you could say is how I look at writing and sharing at least the type of writing that we do. nonfictional kind of more instructional writing. But I think my current edge is just increasing collaboration with my team, my email list, you know, I have, I already have a huge asset, which is my email list, which is like the people I have already served enormous amount I want to keep serving them. The other edge I have is, and I don’t know if I’ll be doing this my whole career, I imagine I’ll be doing content, but maybe not as Benjamin hardy into the future, maybe I’ll do it for some other organization to support their goals, but I think for the next three to five years, let’s say my edges, one I’ve got now six kids, and I kind of actually have a need to support that family. And I don’t want to so like I know. And creating content is the way that I like to do that teaching sharing. Another edge i think i have is that I’m okay, creating stuff that doesn’t work. Like, for example, YouTube, as an experiment, I know, I’m going to create 400 YouTube videos in the next, let’s just say, a year and a half, two years, I’ve already paid people to edit those videos. And I’m fine. I’m fine. If 80% of you said 400 videos, well, I have a contract with people to make 6060 a month. 060 a month. Yeah, but like, some of them might be two minutes long. And it might just be a really terrible thought vomit. And then I publish it because I’m fine doing that. And I’ve also learned that some of my thought vomit articles that were two minutes long were the ones that got 500,000 views. And so you just never really know. Um, so I guess the one edge with that with that approach is quantity leading to quality. And just being okay, with some of it not being that great. Um, so yeah, I think it’s a combination of my situation kind of requires it because I have a family that I want to support and provide for and I want to be successful. I’ve got a, you know, a five year plan of putting myself and my family into a certain financial situation. And this is my pathway to doing it. And so I want to succeed, I want to learn, I’m also fine failing an enormous amount. And I’m increasingly collaborating with people who are already well established in different domains. And what I’ve learned through Who Not How is that collaboration, if done, right does go a lot farther than individual pursuits. You know, like, Who Not How might not be my best book, but it actually might be my best book, even though it took me the least amount of time to write. And it wasn’t even my original idea. And it certainly outperformed as far as sales, all of my other books immediately. And so I find value in aligning goals with other people with different assets, and seeing how much can be accomplished if it’s not just me fully responsible.

Michael Simmons 1:02:55

Hmm, interesting. So it’s almost a combination of mindset, skills, and increasingly, who are the network? How you’re embedding yourself in a network? Yeah, situation,

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 1:03:04

mindset and context, context being increased collaboration in can increase, you know, relationship with other parties that I can align forces with mindset, being willingness to fail a million times. And just knowing that it’s not really going to be a failure, you know, like, if I make if I make 10 videos, you know, five of them will be pretty good. Like, yeah, I already know that. And so like, if I’m okay with that, and then as far as a situation, just my family and my goals. Right, right. It’s,

Michael Simmons 1:03:37

it’s just fascinating that you’re not even saying, I’m the same way that writing when people think about online writing, they think about the three key skill is writing itself. But you’re not saying writing I hear you saying a lot of other things. And I feel like you can. I don’t feel like I’m a bad writer. But I don’t feel like I’m a great writer. But I In other words, when I read James Altucher, or something, I know he’s read a ton of fiction, and he does all these turns of phrases. I’m like, wow, he’s really, really good. And I want to be better. But I think the amazing thing is that you’re really good at thinking about your ideas, and packaging your ideas. That’s really the most important thing and the quality of the idea. You don’t have to be the next. No, great, not late, great novelist.

Dr. Benjamin Hardy 1:04:22