Most People Think This Is A Smart Habit, But It’s Actually Brain-Damaging

This is the mental equivalent of eating McDonald’s every day.

As someone who has studied, practiced, and taught learning how to learn for years, I’ve come to believe that one of the most pervasive threats to our brains goes completely unnoticed.

When we think of brain damage, we think of a head injury impairing a person’s ability to think. There are laws in place that require us to wear helmets, use seatbelts, and generally do everything we can to avoid head injuries. Why? Because we know how important our brain is for leading a fulfilling, impactful, and successful life.

But a knock on the head isn’t the only way to “impair” our brains. If we think of damage in broader terms, then brain damage can be caused by anything that physically changes our brains in a way that makes us less intelligent or functional. Using this definition I’d make the case that much of the learning that people do on their own, which we usually consider a positive thing, might actually be doing many people more harm than good.

Let me explain.

First, whenever we learn something new, our brain physically changes

More specifically, the brain either makes a new connection between neurons or strengthens an existing one.

In one fascinating study that shows how much learning can change our physical brain, researchers found that certain parts of the brain of London taxi drivers who completed the exhaustive training process were significantly larger than aspiring drivers who dropped out of the training program. This shows that the training program was the cause of the growth.

How the learning impacts the brain is explained in detail in The Art Of The Changing Brain by researcher James Zull.

Second, assuming that all learning is inherently good is like assuming that all food makes us healthier.

Or that most of the news we consume makes us more well-informed. In reality, the opposite is true. The default — the easiest thing to reach for — is often junk food and junk media.

The same is often true with learning. Just like eating McDonald’s doesn’t make us healthier, “junk” or “fake” learning doesn’t make us smarter. In fact this kind of learning actually makes us dumber.

Learning is a circular process of taking in information, reasoning with that information, experimenting in the real world, getting feedback, and then taking what learn to go through the cycle again. When one part of the process is faulty, then it can throw off our learning process. For example, if all we’re collecting is bad ideas, then our reasoning is going to be bad, which is going to lead to ineffective actions and so on.

Later in this article, I’ll share how five strategies to recognize junk learning and avoid it.

Next, junk learning can cause physical changes in our brain, which then hurts our ability to function effectively

If the connections from learning are reinforcing false and harmful concepts, beliefs, or ideas, the physical result can be functionally equivalent to brain damage.

For example, one of the ideas I learned growing up was that sales is a bad thing. This single idea literally changed my brain and made me resistant to information on how to become better at this vital business skill. I had to go through a lot of pain before I was finally willing to let go of this idea. My business grew rapidly and immediately afterwards.

In some ways, it was like I was walking through the world with a hand in front of my face making it so I had huge blind spots. As a result, my brain created a false sense of reality, which led to me bumping into things.

We particularly see how junk learning can be functionally equivalent to brain damage with political polarization. Imagine you had someone come from a completely different culture who was unaware of politics. Then, imagine you had her observe the inability of many political commentators to logically consider an opposing idea without distorting it and attacking the other’s character. That person could easily come to the conclusion that the commentators’ brain had been damaged. Now, consider that this phenomena is in no way limited to politics.

Finally, junk learning is like a disease that spreads throughout the brain and causes more junk learning

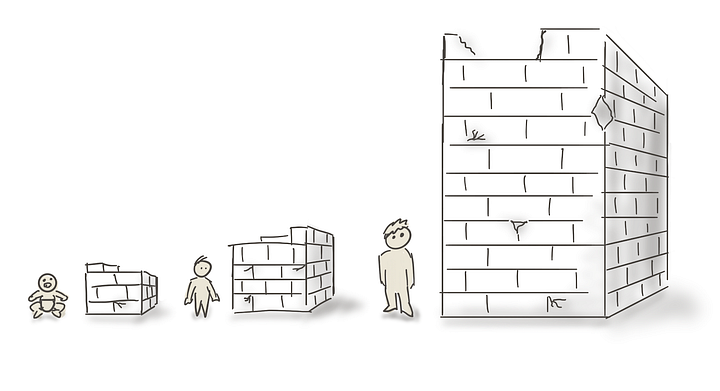

We all share inherent physical growth tendencies. When we’re born, we go through a set of predictable, sequential steps that build on top of each other.

We roll over before we sit. We sit before we stand. We stand before we walk. We walk before we run.

The same thing happens with our cognitive development.

Although it’s not as obvious as physical abilities, ideas in our brain build upon other ideas in a predictable order from simple to complex.

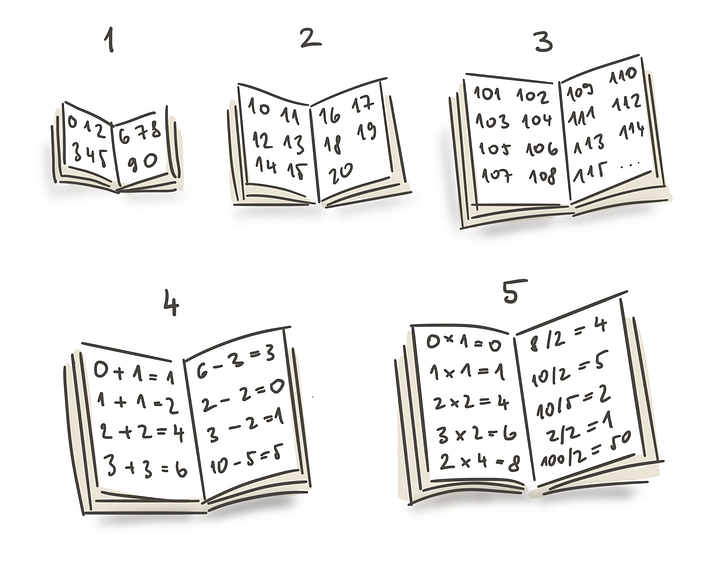

For example, when it comes to math, we start with single digit numbers, move to double digit numbers, then triple digit, then addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and so on.

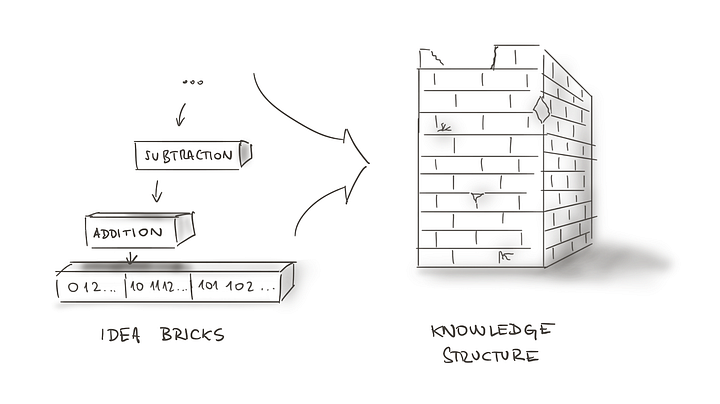

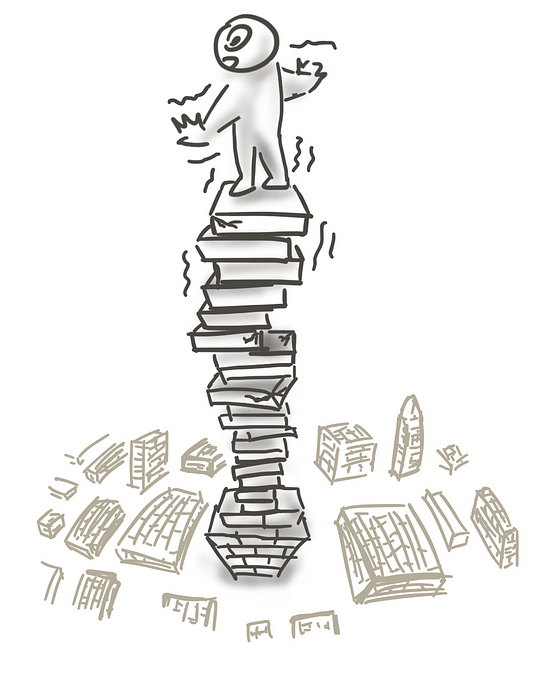

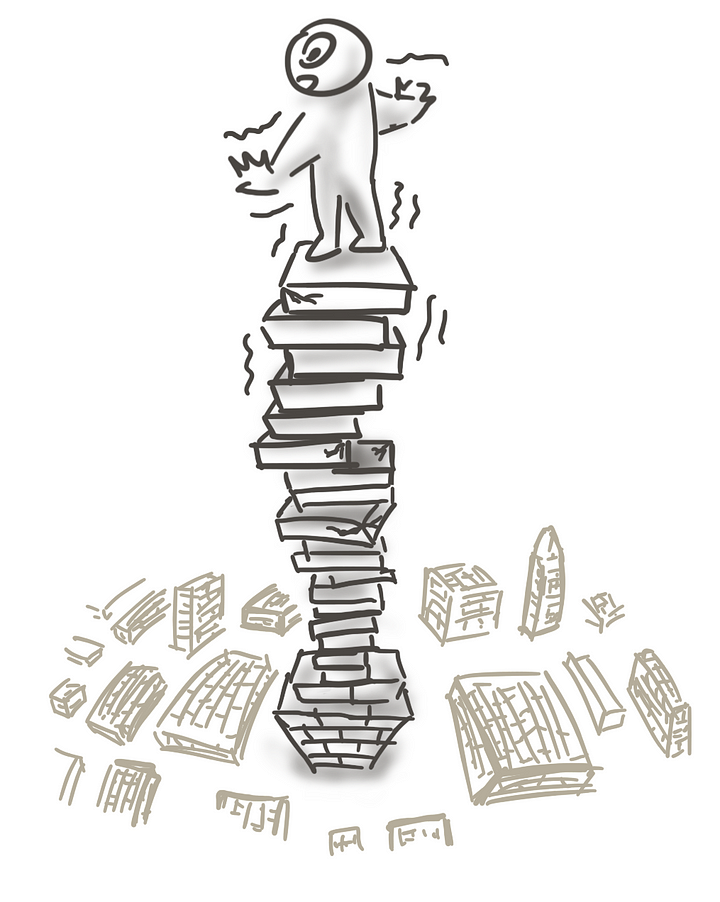

Each new thing we learn is like adding a new brick and then cementing it to other bricks to create a knowledge structure.

As we learn more, our building becomes larger.

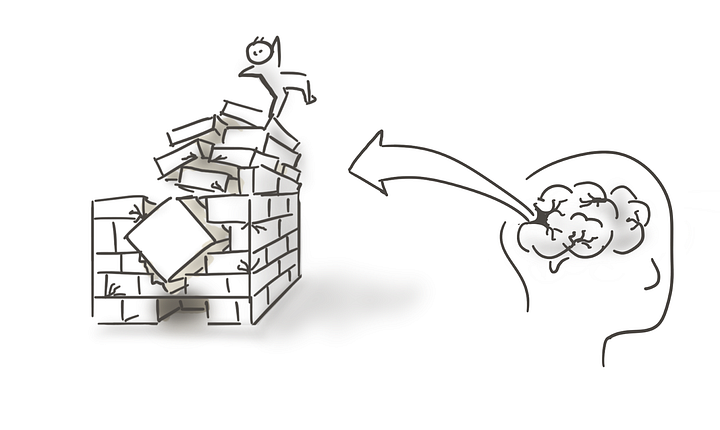

The problem comes when we build our buildings on a poor foundation with shoddy bricks (junk learning). In this case, counterintuitively, adding new knowledge weakens the whole building.

And if we keep adding new knowledge to an unstable building, it eventually falls down. These building collapses are our existential crises (i.e., quarter-life and mid-life crises) where we hit bottom after reconsidering our deepest beliefs. Removing these fundamental ideas forces us to reconsider all of the ideas that were dependent on that idea.

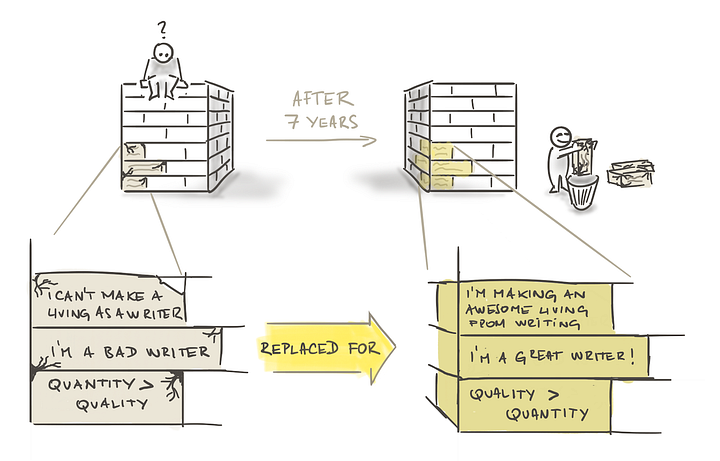

This is what happens in our brains with junk learning. For example, when I first started writing in college, I somehow got the idea in my head that the key to being a good writer was producing as much content as possible. So, for three years, I wrote a new blog post every day.

My hope was that the blog would somehow become viral and be a platform for me to go into a career in writing. Instead, almost no one read my posts, and I eventually gave up and took a different career path that allowed me to support myself. As a result of the experience, I came to the conclusion that I just wasn’t a good writer and that you can’t really support yourself as an independent writer. Two more false ideas built upon on a bad one.

I didn’t come back to writing for 7 years. Fortunately, when I started writing for Forbes in 2013, I had just read a book called Blockbusters by Harvard professor Anita Elberse. The central premise is that the best strategy in the media world of books, movies, TV, and music is to focus on creating high-quality blockbusters rather than churn out volume. Elberse based her claims on years of research on who the winners are in the media world.

I applied the blockbuster idea and immediately it started working for me. Today, I am a writer and teacher full-time.

It is painful to think about how big of a detour was caused by the initial faulty idea.

Bottom line: Junk learning damages our brain and then it makes us more prone to more junk learning, which damages our brain even more.

The Top Five Sources Of Junk Learning

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” — Alvin Toffler

Ok. So we’ve established a few things:

- Learning physically changes our brain.

- Much of the learning that people are exposed to by default is junk learning.

- Junk learning effectively equivalent to brain damage and impairs our ability to function in the world.

- Junk learning is like a disease that spreads throughout the brain and causes more junk learning.

Now the question is, what do we do about it?

In my experience, it’s key to first know what the causes of junk learning are. This way we can avoid them the next time we jump into an audiobook or start a learning ritual.

What follows are the five biggest sources of junk learning that I’ve personally come across over and over…

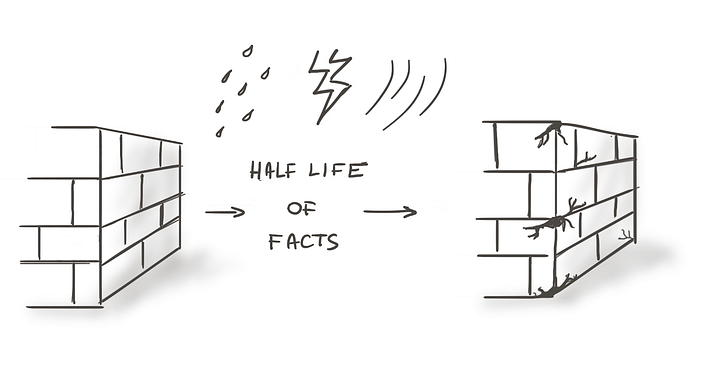

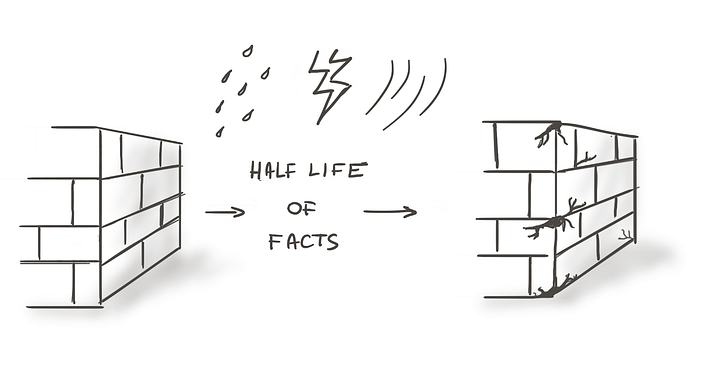

Junk Learning Source #1. The “Facts” We Know Are Slowly Being Debunked

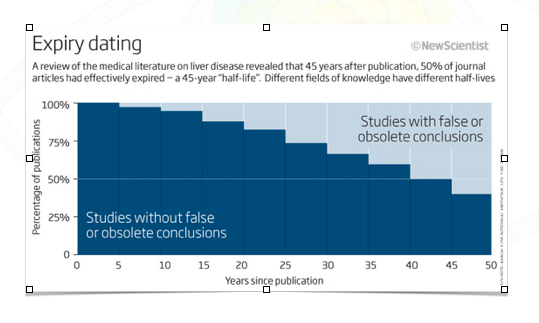

At the same time that we are building up our base of knowledge, the knowledge is expiring. The book that woke me up to this reality is The Half Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has An Expiration Date, which terrified me by revealing that if you’ve got liver disease and go to a doctor who graduated more than 45 years ago, half of that doctor’s information is probably wrong:

It’s not just medicine. It’s happening in computer science, design, nutrition, psychology, basically everywhere. It’s like we’re trying to bail water out of a leaking boat. We have all this knowledge, but it’s losing value. And to make it worse, we don’t even know when a piece of knowledge expires. It’s not like we get an email notifying us: “Hey, that thing you learned three years ago? It’s not true anymore.”

The end result is that we operate with false ideas and we stop getting results. Then we have to troubleshoot to find out what out-of-date knowledge and skills might be responsible for the poor results.

A fascinating 1966 paper titled The Dollars and Sense of Continuing Education plays out the implications of decaying knowledge. Assuming that it takes ten years for half the facts in a given field to be proven wrong or improved on, then:

- You would need to spend at least five hours per week, 48 weeks a year, to stay up to date.

- A 40-year career would require 9,600 hours of continuing learning just to stay relevant. This does not include learning to get ahead or the time it would take to simply remember what we have already learned.

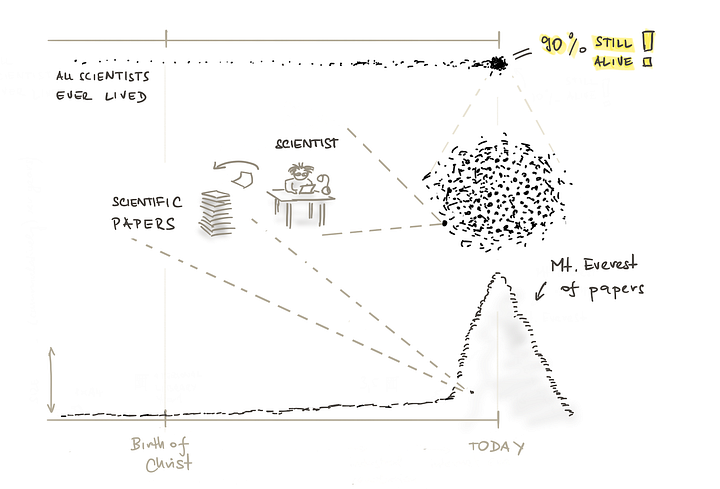

Now, if that isn’t enough to blow your mind, consider that 90 percent of the scientists who have ever lived are alive today. Each of these scientists is increasing the rate at which new information is created and old information decays. Also, consider that some of the most interesting and consequential future fields (for instance, artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency) change the fastest.

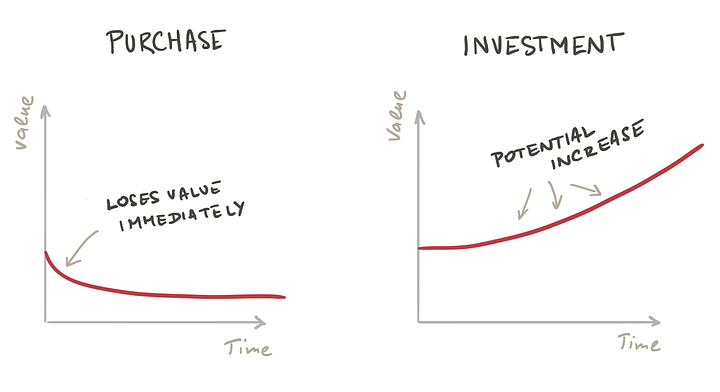

So what should we do in light of all of this change? One model I’ve found helpful comes from the world of personal finance.

One of the biggest distinctions in the world of personal finance is between purchases and investments. Purchases immediately lose value while investments have the potential to increase in value. For example, a car is a purchase — the second you drive a new car off the parking lot, it loses value. A home, on the other hand, is an investment: It has the potential to increase in value.

Learning is very similar. Certain knowledge is going to predictably decline in value. If you read the New York Times №1 bestseller about business or the latest fad diet, chances are it will be forgotten in a year. Other knowledge has the potential to become even more valuable: If you read a classic book that’s been around for centuries, chances are you will glean wisdom that is more universal and long-lasting.

Learning is like running on a treadmill. As the speed of the treadmill increases, you need to run faster or you’ll be thrown off. Similarly, as society changes more rapidly, you need to update your skills more rapidly or risk falling off into irrelevancy. Depending on outdated knowledge to get results in life is like depending on termite-eaten beams to hold a building up.

While you still need to keep on top of cutting-edge breakthroughs in a field, in general, many people undervalue learning investments in a stable base of knowledge that doesn’t change. In my opinion, mental models are one of the best learning investments anyone can make, because they apply across fields and across time, and will continue to apply to many situations in the future.

Lesson Learned: Look for information that actually increases in value over time. When it comes to knowledge, think like an investor, not a consumer.

Junk Learning Source #2: A Little Knowledge Is Dangerous

“The greatest obstacle to knowledge is not ignorance; it is the illusion of knowledge.” — Historian Daniel Boorstin

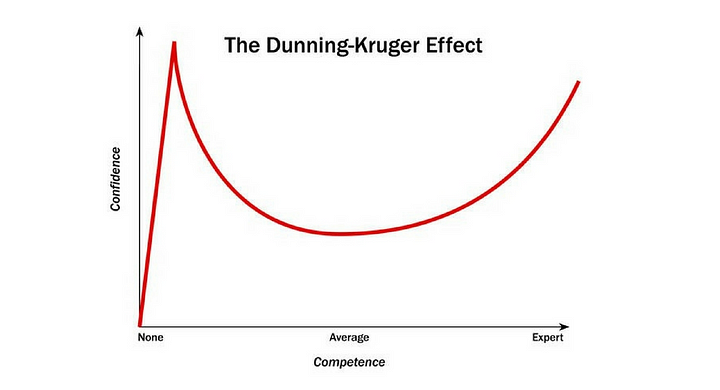

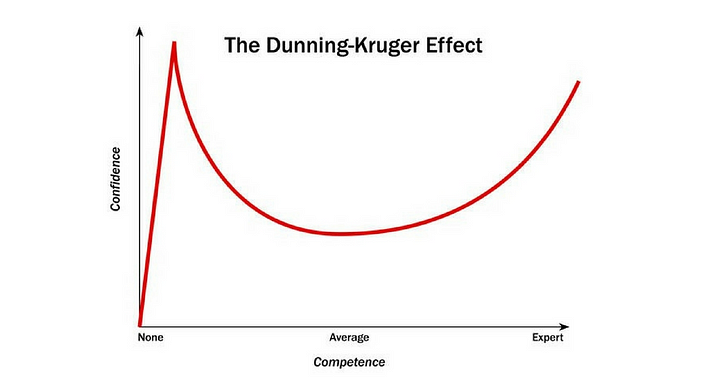

In 1999, psychologists Justin Kruger and David Dunning wrote a research paper, that introduced us to the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The idea is simple but counterintuitive: In learning any new domain, our confidence is actually highest when we start. This is surprising because, rationally, we should have the lowest confidence when we know the least. However, Dunning and Kruger found that when we don’t know what we don’t know, we overestimate our abilities. Or, as philosopher Bertrand Russell famously put it: “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.”

Of course, once we have our bubble burst and learn enough to recognize our ignorance, most people’s confidence takes a huge dip. It only slowly rebounds if we keep going. Unfortunately, many give up during the dip phase.

I’ve experienced the Dunning-Kruger effect myself. When I was 16 years old, Cal Newport and I co-founded a company together during the height of the dotcom boom. With barely any advertising we quickly got clients willing to pay us over $100 per hour. At the time, the only way I could explain this was that we were brilliant and everyone else who was decades older and making a lot less wasn’t. Then, in 2001, the Internet bubble burst and the business cratered. I learned that my self-confidence was wildly over-inflated, that I was missing key business skills, and that tech and economic cycles are a real thing.

It took several years for me to admit my ignorance because my self-image had been so big. And it took several more years to regain my confidence.

Lesson Learned: No matter how much we know, we only know a fraction of all there is to know. We must assume our own ignorance. An attitude of caution can help us avoid developing false beliefs that can lead to irrational decisions.

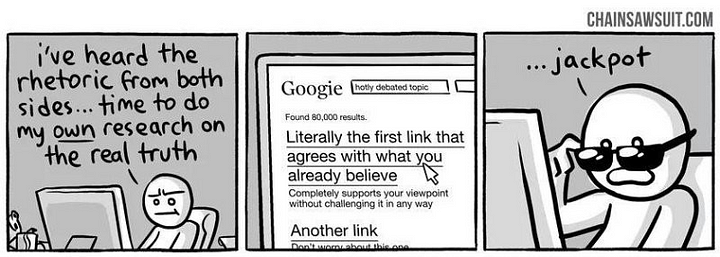

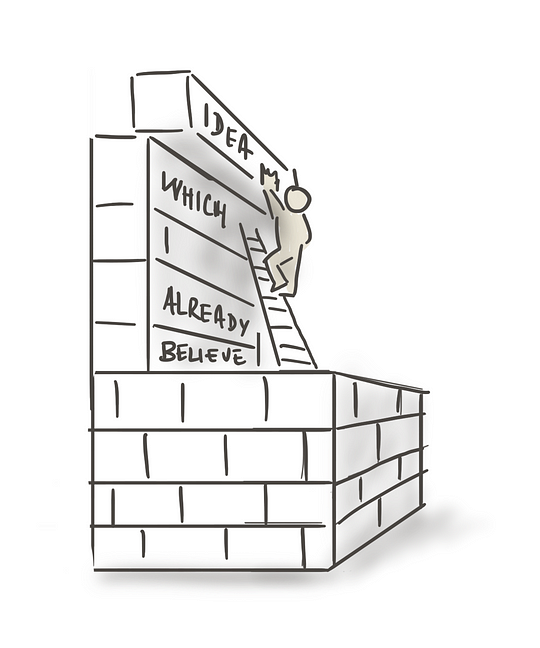

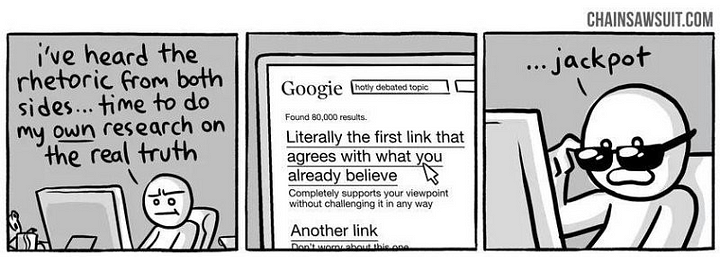

Junk Learning Source #3: Our Confirmation Bias Makes Us Progressively More Dumb

Copernicus published his thesis that the Earth revolves around the sun in 1543. Ninety years later, Galileo was arrested for agreeing with Copernicus. It took more than a hundred years for this model to be accepted — and 350 years for the Catholic church to officially accept it.

Confirmation bias is our tendency to only look for and believe information that supports what we already think, and to dismiss evidence to the contrary. And this example drives home just how powerful it is.

It also drives home another important lesson. A very small amount of disconfirming evidence can disprove a much larger body of confirming evidence. Consider how easy it must have been to believe that hat the sun revolves around the Earth — when for millennia all humans could see was the sun moving around us through the sky each day. Each incremental piece of evidence seemed to prove our original ideas right.

One of the biggest daily examples of confirmation bias involves our social media bubbles: We read the same sites, listen to the same friends (who agree with us!), and watch the same news over and over, which only confirms what we already believe. When we’re exposed to something that doesn’t fit our model of the world, we unconsciously either ignore it, minimize it, or attack it.

When we only hear opinions that confirm our beliefs, our learning is incremental at best. We learn the most by proving ourselves wrong, not by proving ourselves right. Many of the greatest thinkers of the 20th century independently came to this conclusion.

Karl Popper, one of the greatest philosophers of science, explained that what moves science forward is actually the discovery of disconfirming evidence.

Joseph Schumpeter, one of the greatest economists, showed that ideas don’t simply progress in a straight line forward. They grow through a process of creative destruction where old ideas are destroyed to make way for new paradigms.

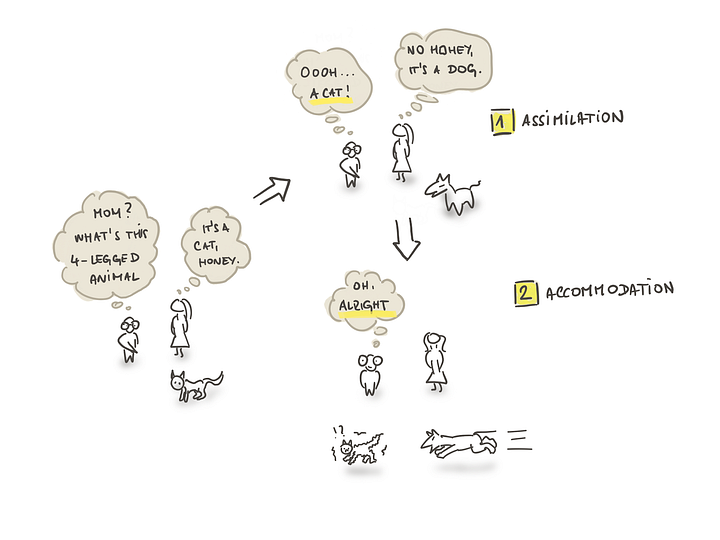

Jean Piaget, one of the greatest psychologists, showed that we grow our own knowledge the most when we transform our thinking to be able to accomodate external knowledge that doesn’t fit at first. In his model, when we are exposed to new information, we adapt to it in one of two ways:

- Assimilation — We use our existing base of knowledge to understand a new object or situation.

- Accommodation — We realize that our existing base of knowledge does not work, and needs to be changed in order to effectively deal with a new object or situation.

The following example shows the difference between assimilation and accommodation. Imagine, a three-year-old child who sees a cat for the first time and asks his mother, “Mommy? What’s that four-legged creature?” Smiling, she responds, “It’s a cat, honey.”

The next day, the boy is walking through his neighborhood with his mom, and he sees another four-legged creature, a dog. He excitedly turns to his mom and says, “Mommy… Mommy… oooh. Another cat!” Correcting him, she says, “No honey, it’s a dog.” The boy furrows his eyebrows in deep thought. He points to the dog and half asks half says, “doggy?!?!” His mom proudly replies, “That’s right! Good job.” and they continue their stroll.

What happened here?

The boy first tried to assimilate the new knowledge by fitting it into his existing schema. Cats have four legs. So do dogs. So they are the same.

When his mom corrected him, he went into deep thought because he needed to update his schema on what a cat was in order to understand what a dog was.

Popper, Schumpeter, and Piaget show that we stunt our growth when we ignore disconfirming evidence or distort evidence in order to make it assimilate with our existing knowledge. Focusing on learning what we already we believe is like building a really skinny wall that will topple over as it gets larger.

On the other hand, we go through a growth spurt when we actively search for disconfirming evidence and allow accomodation to happen.

It’s easier said than done because we hate to admit when we are wrong. Counteracting confirmation bias takes incredible psychic energy. It is the equivalent of doing strenuous physical exercise; it’s difficult, but worth it.

A fascinating study at the University Of Southern California shows just how unsettling it can be to go against our confirmation biases. In the study, participants had their brain scanned while they were presented with counterarguments to some of their political beliefs, such as:

- “Laws restricting gun ownership should be made more restrictive.”

- “Gay marriage should not be legalized.”

Amazingly, what the study found is that the same parts of the brain (for example, the amygdala) that respond to PHYSICAL threats also respond to INTELLECTUAL threats. In other words, reading about facts we disagree with can provoke the same sort of response we’d feel if we were being chased by a lion.

Matthew Inman, the creator of The Oatmeal, beautifully sums up how most of us protect our confirmation bias instead of attempting to get past it:

To some extent, we all walk around with rickety “knowledge buildings” surrounded by moats; whereas, if we let new, disproving information in, we could strengthen the building instead.

Lesson Learned: We need to identify and stress-test our most fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality— and learn how to handle the strong emotions that will come up when we do.

Junk Learning Source #4. We Trust the Wrong Ideas and the Wrong People

Humans are social learners. We watch someone do something and emulate it. If you’re a parent, you’ve seen this firsthand in your child. You say something or make a facial expression, and your little one copies it.

We often take the ability to mimic others for granted. But I see it as a superpower. In fact, it’s actually the superpower of a superhero in one of my favorite TV shows. This superhero is able to watch anyone do anything once and immediately master it:

But this superpower can go wrong if we copy the wrong things from the wrong people. Unfortunately, we do this all of the time as a result of the Halo Effect. This is a cognitive bias that makes us trust a person’s advice in one area of life simply because they are an expert in another area. Researcher Phil Rosenzweig breaks it down further in his book The Halo Effect (one of my favorite business books of all time):

…a tendency to make inferences about specific traits on the basis of a general impression. It’s difficult for most people to independently measure separate features; there’s a common tendency to blend them together.

It’s like buying a Lincoln car because Matthew McConaughey drives one in a Superbowl ad. It’s listening to a famous painter give his or her grand plan for re-engineering society. It’s trusting a scientist to tell us what’s wrong with our political system when that scientist has no experience in politics. It’s following the fashion advice of a professional athlete. It’s trusting the advice of a business celebrity who turned around a big company 10 years ago and wrote a bestselling book to help us grow our startup.

While these examples may seem obvious, the Halo Effect also shows up in much more subtle ways that are harder to recognize:

In the autumn of 2001, after the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush’s overall approval rating rose sharply. No surprise there, as the American public closed ranks behind its president. But the number of Americans who approved of President Bush’s handling of the economy also rose — from 47 percent to 60 percent. Now, whether or not you like Bush’s economic policies, there’s no reason to believe that his handling of the economy was suddenly better in the weeks after September 11. But it’s hard to keep these things separate: General approval of the president carried over to approval of a specific policy. The American public conferred a Halo on its president and made favorable attributions across the board. After all, it’s uncomfortable for many people to believe that their president might be good on issues of national security but ineffective on the economy — it’s far easier to think he’s about the same for both.

And ultimately, the example in the book that really drove home the point was the takedown of Jim Collins’ books Good To Great and Built To Last, two of the bestselling business books of all time. I had read each of these multiple times and looked upon them very highly. Collins and his team spent thousands and thousands of hours identifying:

- Companies that had outperformed their peers by a large margin over decades.

- The qualities that made them successful.

Yet, when Rosenzweig explored how the companies did after the books came out, the results are humbling:

Collins and Porras urge us not to “blindly and unquestioningly accept” their findings but ask that we subject their analysis to careful scrutiny. “Let the evidence speak for itself,” they implore. So let’s check the evidence. We may not be able to put companies in petri dishes and run experiments, but we can check how they fare over time. If the principles of Built to Last are indeed timeless and enduring explanations of performance, then we should expect these same companies to continue to perform well after the study ended. Conversely, if they can’t keep up their high performance, well, that would lend support to the view that these so-called timeless principles were due mostly to the Halo Effect — a glow cast by high performance rather than the cause of high performance.

So how well did the eighteen Visionary companies fare in the years after the study ended on December 31, 1990? All eighteen were still up and running in 2000, so at least they were built to last for another ten years. But as for performance, the record wasn’t so good. Using data from Compustat, I looked at total shareholder return for each company for the five years after the study ended, 1991– 1995. The results? Out of seventeen companies, chosen specifically because they had outperformed the market by a factor of 15 for more than sixty-four years, only eight outperformed the S& P 500 market average; the other nine didn’t even keep up.

An analysis of Good To Great companies after the book came out had similar results.

We fall for the Halo Effect in our professional lives when we buy books or get mentors and don’t discount that what worked in their industry, in the past, at their size company, in one specific department many not work for us too.

We also fall for the Halo Effect when we have a success and generalize it too far like I did earlier in my career when I attributed our success to personal genius rather than an economic cycle.

Lesson Learned: As a result of reading The Halo Effect, I’ve become much more suspicious of listening to celebrity experts in any field. Instead, now whenever I look at who to emulate, I specifically look for people who have experienced success over and over not because of luck or celebrity, but because of skill. In my experience, many of these individuals are not celebrities. Then, I carefully experiment with their advice to see if it will transfer to my context.

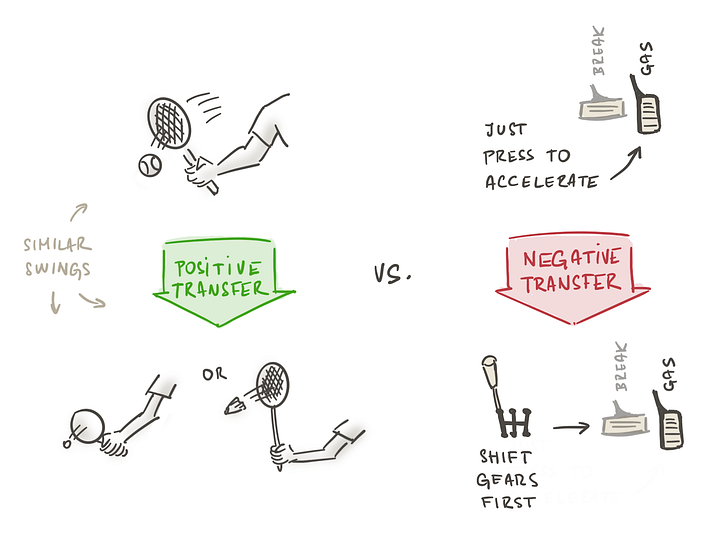

Junk Learning Source #5. Over-specialization limits our ability to learn across disciplines

In other articles, I’ve written about learning transfer. This is our ability to learn a concept in one domain and then apply it to another.

In learning science, positive transfer is when learning something makes it more likely that we will transfer our knowledge. Learning addition and subtraction, for example, help children then learning multiplication and division. Learning to play one racket sport like tennis can help others learn to play other racket sports like badminton and table tennis.

Negative transfer, on the other hand, is when learning something hinders learning transfer.If you’ve ever switched from driving an automatic transmission to a manual one, you’ve had to unlearn the habit of simply pressing the gas, and get used to engaging the clutch and shifting gears before accelerating. If your first language is a European one like Spanish, French, or German, you’ve had to get over the fact that in English, nouns have no gender. Or consider the all-too-familiar case of a software password. Just when you finally memorize one, you get asked to create a new one. Do this a few times, and it’s hard to remember which password to key in because you keep getting them confused.

Scarily, research in the field of expert performance shows that these negative transfer effects can:

“…get worse as higher levels of expertise are reached, as the acquired knowledge becomes increasingly specialized. This is because the perceptual chunks, which act as the condition part of productions, become more selective…

Interestingly, the author’s suggestions to this challenge parallel our approach of using the trunk technique:

If this analysis is correct, and keeping in mind that it is difficult to predict what skills will be required two or three decades from now, the best option seems to supplement the teaching of specific knowledge with the teaching of metaheuristics that are transferable (Grotzer & Perkins, 2000; Simon, 1980). These may include strategies about how to learn, how to direct one’s attention in novel domains, and how to monitor and regulate one’s limited resources, such as small STM [short-term memory] capacity and slow learning rates.”

Lesson Learned: Being too specialized can hurt future learning if done alone. Supplement by spending more of your time learning fundamental knowledge that doesn’t change. This is why we created the Mental Model Club.

Take Action: Strengthen Your Brain Instead of Damaging It

Just as learning what junk food is can help us eat healthier, learning how NOT to learn can help us learn faster and better. Remember these junk learning sources, and their solutions, so you can recognize and avoid them.

1. Our “facts” are expiring and we don’t even know it.

Look for information that actually increases in value over time. When it comes to knowledge, think like an investor, not a consumer.

2. A little knowledge is dangerous.

Realize you only know a little bit. Assume ignorance to avoid developing false beliefs that can lead to irrational decisions.

3. Our confirmation bias makes us progressively more dumb.

Identify and stress-test your most fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality — and learn how to handle the strong emotions that will come up when you do.

4. We too often trust the wrong ideas and the wrong people.

Remember that celebrities are often not experts at anything except their specific field of celebrity (music, acting, a sport, etc.). Be super careful about whom and what you choose to emulate.

5. Over-specialization limits our ability to learn across disciplines

Specialized knowledge can hurt future learning. Instead, spend most of your time learning fundamental knowledge that doesn’t change such as mental models.

Knowledge doesn’t innately compound to make us smarter. In fact, as we learned in this article, it is possible for people to actually become dumber as they put in more learning time.

Here’s How to Master Mental Models

In our Mental Model Club, we help you learn the most fundamental mental models and principles that will last forever and that you can apply in ever area of your life. Each month, you receive a 15,000-word Mastery Manual that condenses dozens of books into a how-to guide with workbook and resource list. By joining now, you will get our best Mastery Manual.

| - | I teach people to learn HOW to learn |

| - | Bootstrapped million dollar social enterprises |

| - | Best-selling author |

| - | Contributor: Time, Fortune, and Harvard Business Review |

| - | Alum: Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year, Inc. 30 under 30, Businessweek 25 under 25 |

| - | Creator of the largest learning community in the world |

| - | Have read thousands of books |

Read more about me…