Most People Think This Is A Smart Habit, But It’s Actually Brain-Damaging

This is the mental equivalent of eating McDonald’s every day.

As someone who has studied, practiced, and taught learning how to learn for years, I’ve come to believe that one of the most pervasive threats to our brains goes completely unnoticed.

When we think of brain damage, we think of a head injury impairing a person’s ability to think. There are laws in place that require us to wear helmets, use seatbelts, and generally do everything we can to avoid head injuries. Why? Because we know how important our brain is for leading a fulfilling, impactful, and successful life.

But a knock on the head isn’t the only way to “impair” our brains. If we think of damage in broader terms, then brain damage can be caused by anything that physically changes our brains in a way that makes us less intelligent or functional. Using this definition I’d make the case that much of the learning that people do on their own, which we usually consider a positive thing, might actually be doing many people more harm than good.

Let me explain.

First, whenever we learn something new, our brain physically changes

More specifically, the brain either makes a new connection between neurons or strengthens an existing one.

In one fascinating study that shows how much learning can change our physical brain, researchers found that certain parts of the brain of London taxi drivers who completed the exhaustive training process were significantly larger than aspiring drivers who dropped out of the training program. This shows that the training program was the cause of the growth.

How the learning impacts the brain is explained in detail in The Art Of The Changing Brain by researcher James Zull.

Second, assuming that all learning is inherently good is like assuming that all food makes us healthier.

Or that most of the news we consume makes us more well-informed. In reality, the opposite is true. The default — the easiest thing to reach for — is often junk food and junk media.

The same is often true with learning. Just like eating McDonald’s doesn’t make us healthier, “junk” or “fake” learning doesn’t make us smarter. In fact this kind of learning actually makes us dumber.

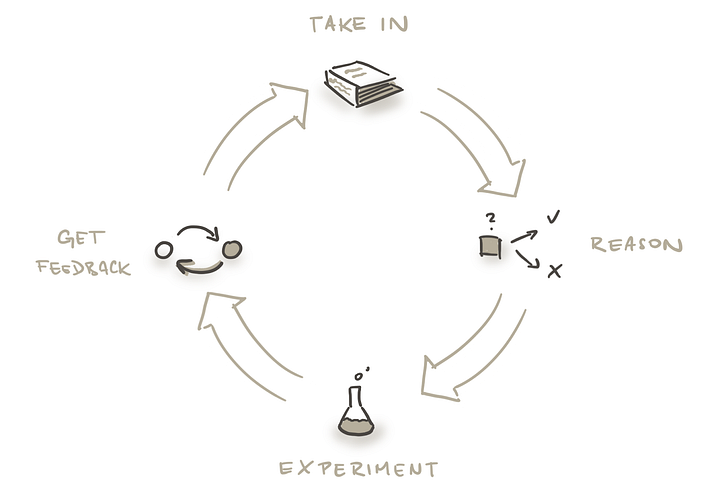

Learning is a circular process of taking in information, reasoning with that information, experimenting in the real world, getting feedback, and then taking what learn to go through the cycle again. When one part of the process is faulty, then it can throw off our learning process. For example, if all we’re collecting is bad ideas, then our reasoning is going to be bad, which is going to lead to ineffective actions and so on.

Later in this article, I’ll share how five strategies to recognize junk learning and avoid it.

Next, junk learning can cause physical changes in our brain, which then hurts our ability to function effectively

If the connections from learning are reinforcing false and harmful concepts, beliefs, or ideas, the physical result can be functionally equivalent to brain damage.

For example, one of the ideas I learned growing up was that sales is a bad thing. This single idea literally changed my brain and made me resistant to information on how to become better at this vital business skill. I had to go through a lot of pain before I was finally willing to let go of this idea. My business grew rapidly and immediately afterwards.

In some ways, it was like I was walking through the world with a hand in front of my face making it so I had huge blind spots. As a result, my brain created a false sense of reality, which led to me bumping into things.

We particularly see how junk learning can be functionally equivalent to brain damage with political polarization. Imagine you had someone come from a completely different culture who was unaware of politics. Then, imagine you had her observe the inability of many political commentators to logically consider an opposing idea without distorting it and attacking the other’s character. That person could easily come to the conclusion that the commentators’ brain had been damaged. Now, consider that this phenomena is in no way limited to politics.

Finally, junk learning is like a disease that spreads throughout the brain and causes more junk learning

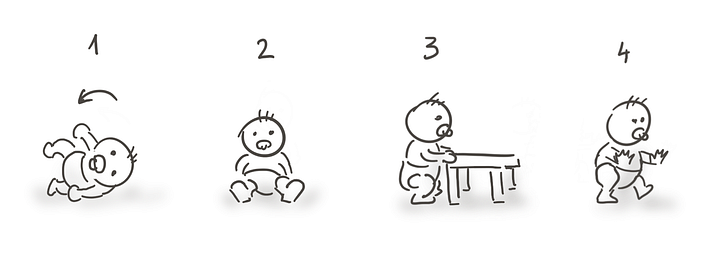

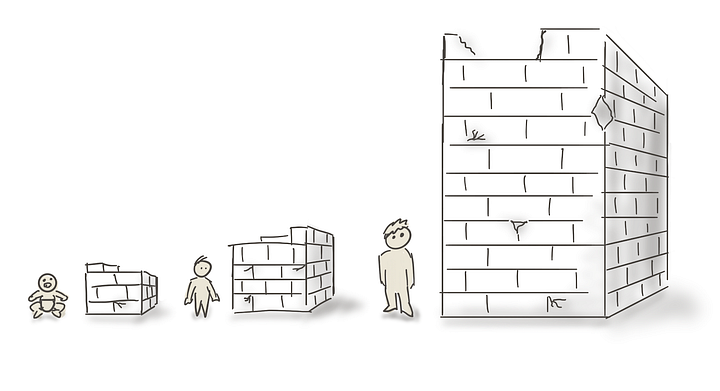

We all share inherent physical growth tendencies. When we’re born, we go through a set of predictable, sequential steps that build on top of each other.

We roll over before we sit. We sit before we stand. We stand before we walk. We walk before we run.

The same thing happens with our cognitive development.

Although it’s not as obvious as physical abilities, ideas in our brain build upon other ideas in a predictable order from simple to complex.

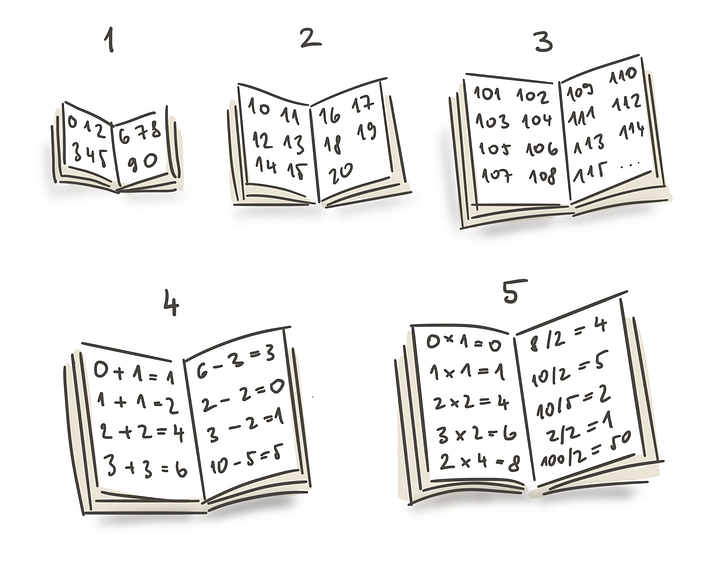

For example, when it comes to math, we start with single digit numbers, move to double digit numbers, then triple digit, then addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and so on.

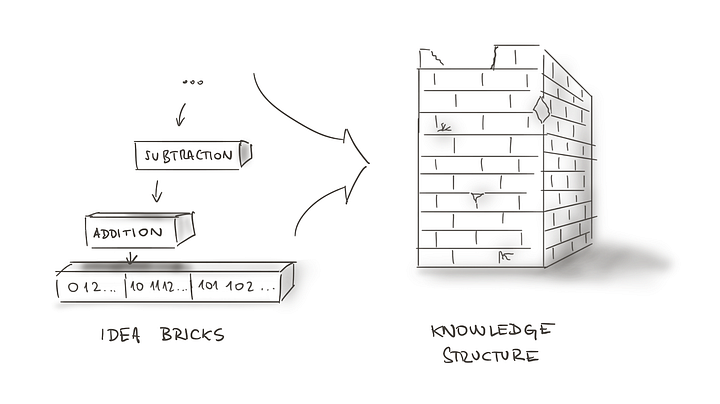

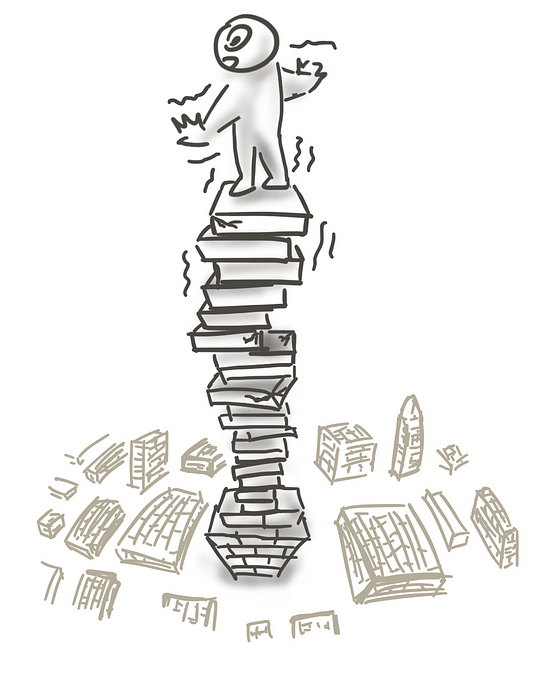

Each new thing we learn is like adding a new brick and then cementing it to other bricks to create a knowledge structure.

As we learn more, our building becomes larger.

The problem comes when we build our buildings on a poor foundation with shoddy bricks (junk learning). In this case, counterintuitively, adding new knowledge weakens the whole building.

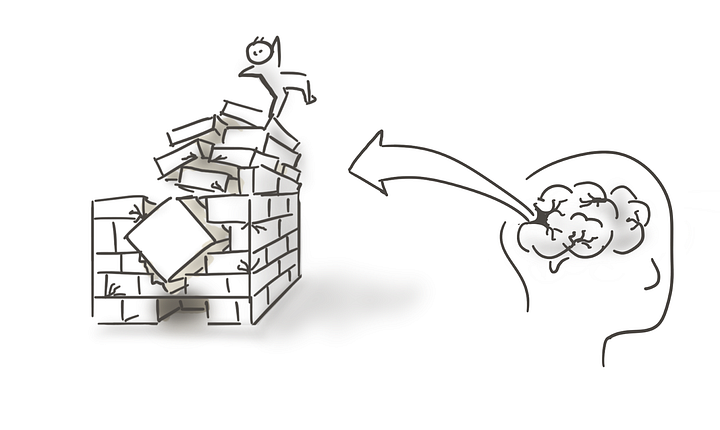

And if we keep adding new knowledge to an unstable building, it eventually falls down. These building collapses are our existential crises (i.e., quarter-life and mid-life crises) where we hit bottom after reconsidering our deepest beliefs. Removing these fundamental ideas forces us to reconsider all of the ideas that were dependent on that idea.

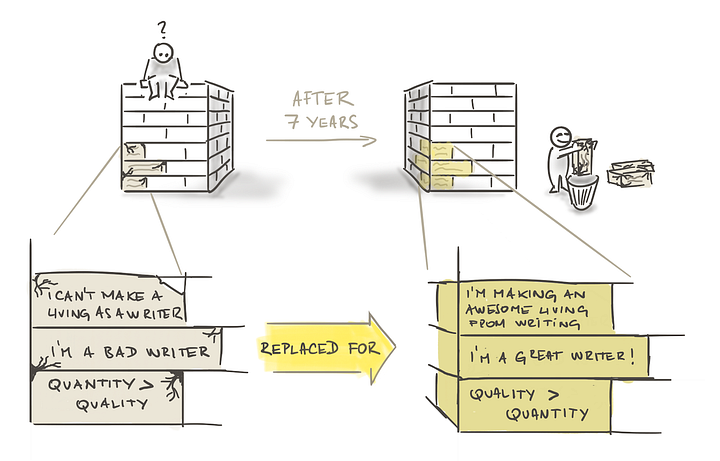

This is what happens in our brains with junk learning. For example, when I first started writing in college, I somehow got the idea in my head that the key to being a good writer was producing as much content as possible. So, for three years, I wrote a new blog post every day.

My hope was that the blog would somehow become viral and be a platform for me to go into a career in writing. Instead, almost no one read my posts, and I eventually gave up and took a different career path that allowed me to support myself. As a result of the experience, I came to the conclusion that I just wasn’t a good writer and that you can’t really support yourself as an independent writer. Two more false ideas built upon on a bad one.

I didn’t come back to writing for 7 years. Fortunately, when I started writing for Forbes in 2013, I had just read a book called Blockbusters by Harvard professor Anita Elberse. The central premise is that the best strategy in the media world of books, movies, TV, and music is to focus on creating high-quality blockbusters rather than churn out volume. Elberse based her claims on years of research on who the winners are in the media world.

I applied the blockbuster idea and immediately it started working for me. Today, I am a writer and teacher full-time.

It is painful to think about how big of a detour was caused by the initial faulty idea.

Bottom line: Junk learning damages our brain and then it makes us more prone to more junk learning, which damages our brain even more.

The Top Five Sources Of Junk Learning

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” — Alvin Toffler

Ok. So we’ve established a few things:

- Learning physically changes our brain.

- Much of the learning that people are exposed to by default is junk learning.

- Junk learning effectively equivalent to brain damage and impairs our ability to function in the world.

- Junk learning is like a disease that spreads throughout the brain and causes more junk learning.

Now the question is, what do we do about it?

In my experience, it’s key to first know what the causes of junk learning are. This way we can avoid them the next time we jump into an audiobook or start a learning ritual.

What follows are the five biggest sources of junk learning that I’ve personally come across over and over…

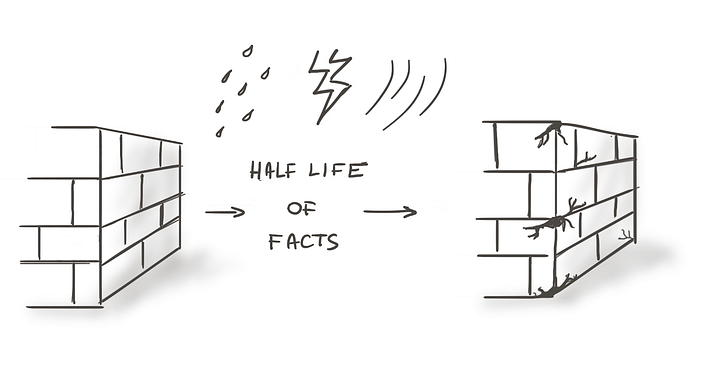

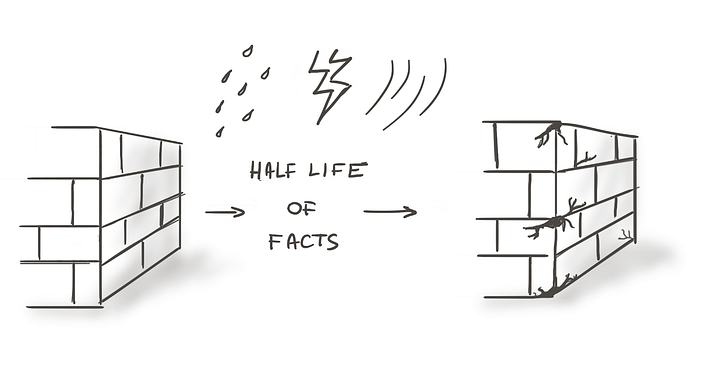

Junk Learning Source #1. The “Facts” We Know Are Slowly Being Debunked

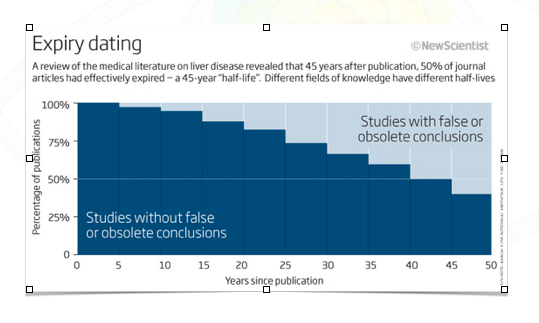

At the same time that we are building up our base of knowledge, the knowledge is expiring. The book that woke me up to this reality is The Half Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has An Expiration Date, which terrified me by revealing that if you’ve got liver disease and go to a doctor who graduated more than 45 years ago, half of that doctor’s information is probably wrong:

It’s not just medicine. It’s happening in computer science, design, nutrition, psychology, basically everywhere. It’s like we’re trying to bail water out of a leaking boat. We have all this knowledge, but it’s losing value. And to make it worse, we don’t even know when a piece of knowledge expires. It’s not like we get an email notifying us: “Hey, that thing you learned three years ago? It’s not true anymore.”

The end result is that we operate with false ideas and we stop getting results. Then we have to troubleshoot to find out what out-of-date knowledge and skills might be responsible for the poor results.

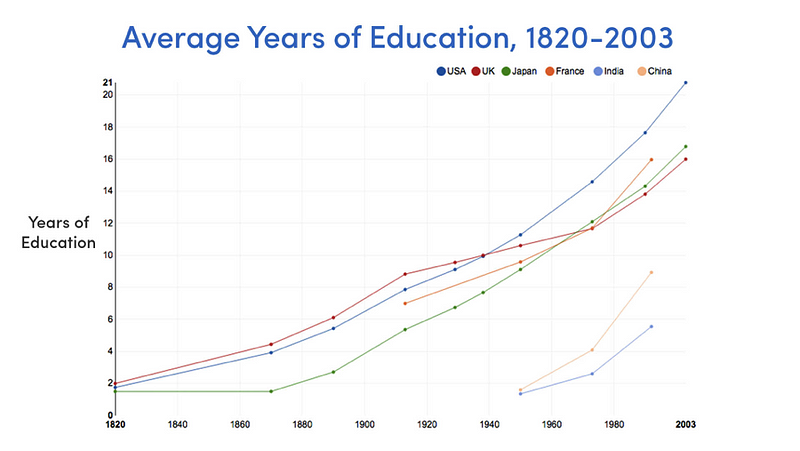

A fascinating 1966 paper titled The Dollars and Sense of Continuing Education plays out the implications of decaying knowledge. Assuming that it takes ten years for half the facts in a given field to be proven wrong or improved on, then:

- You would need to spend at least five hours per week, 48 weeks a year, to stay up to date.

- A 40-year career would require 9,600 hours of continuing learning just to stay relevant. This does not include learning to get ahead or the time it would take to simply remember what we have already learned.

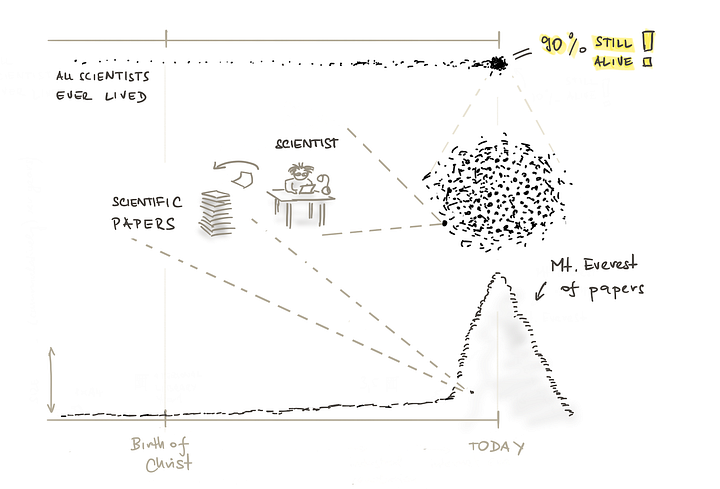

Now, if that isn’t enough to blow your mind, consider that 90 percent of the scientists who have ever lived are alive today. Each of these scientists is increasing the rate at which new information is created and old information decays. Also, consider that some of the most interesting and consequential future fields (for instance, artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency) change the fastest.

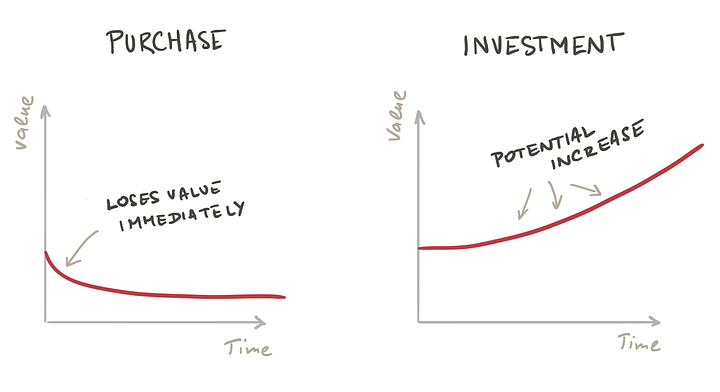

So what should we do in light of all of this change? One model I’ve found helpful comes from the world of personal finance.

One of the biggest distinctions in the world of personal finance is between purchases and investments. Purchases immediately lose value while investments have the potential to increase in value. For example, a car is a purchase — the second you drive a new car off the parking lot, it loses value. A home, on the other hand, is an investment: It has the potential to increase in value.

Learning is very similar. Certain knowledge is going to predictably decline in value. If you read the New York Times №1 bestseller about business or the latest fad diet, chances are it will be forgotten in a year. Other knowledge has the potential to become even more valuable: If you read a classic book that’s been around for centuries, chances are you will glean wisdom that is more universal and long-lasting.

Learning is like running on a treadmill. As the speed of the treadmill increases, you need to run faster or you’ll be thrown off. Similarly, as society changes more rapidly, you need to update your skills more rapidly or risk falling off into irrelevancy. Depending on outdated knowledge to get results in life is like depending on termite-eaten beams to hold a building up.

While you still need to keep on top of cutting-edge breakthroughs in a field, in general, many people undervalue learning investments in a stable base of knowledge that doesn’t change. In my opinion, mental models are one of the best learning investments anyone can make, because they apply across fields and across time, and will continue to apply to many situations in the future.

Lesson Learned: Look for information that actually increases in value over time. When it comes to knowledge, think like an investor, not a consumer.

Junk Learning Source #2: A Little Knowledge Is Dangerous

“The greatest obstacle to knowledge is not ignorance; it is the illusion of knowledge.” — Historian Daniel Boorstin

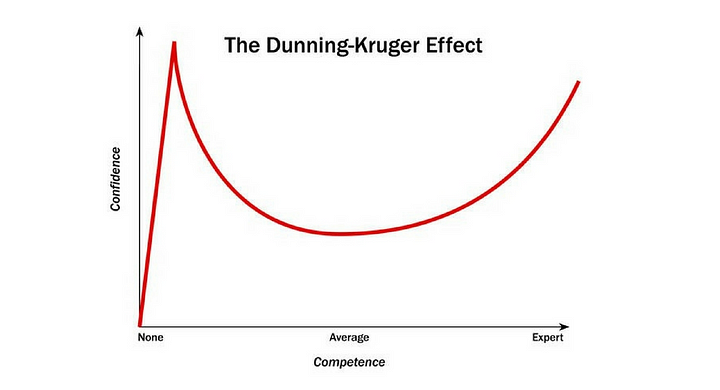

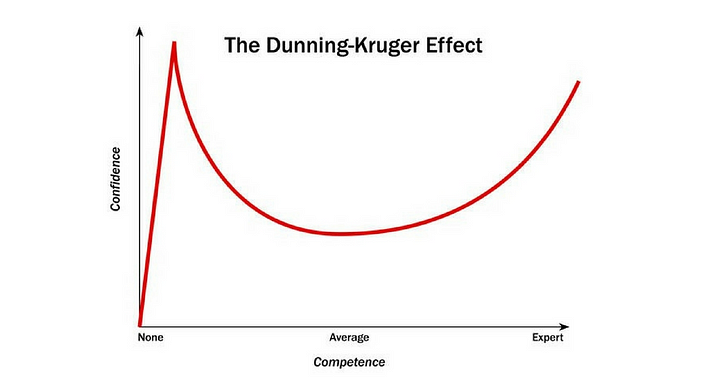

In 1999, psychologists Justin Kruger and David Dunning wrote a research paper, that introduced us to the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The idea is simple but counterintuitive: In learning any new domain, our confidence is actually highest when we start. This is surprising because, rationally, we should have the lowest confidence when we know the least. However, Dunning and Kruger found that when we don’t know what we don’t know, we overestimate our abilities. Or, as philosopher Bertrand Russell famously put it: “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.”

Of course, once we have our bubble burst and learn enough to recognize our ignorance, most people’s confidence takes a huge dip. It only slowly rebounds if we keep going. Unfortunately, many give up during the dip phase.

I’ve experienced the Dunning-Kruger effect myself. When I was 16 years old, Cal Newport and I co-founded a company together during the height of the dotcom boom. With barely any advertising we quickly got clients willing to pay us over $100 per hour. At the time, the only way I could explain this was that we were brilliant and everyone else who was decades older and making a lot less wasn’t. Then, in 2001, the Internet bubble burst and the business cratered. I learned that my self-confidence was wildly over-inflated, that I was missing key business skills, and that tech and economic cycles are a real thing.

It took several years for me to admit my ignorance because my self-image had been so big. And it took several more years to regain my confidence.

Lesson Learned: No matter how much we know, we only know a fraction of all there is to know. We must assume our own ignorance. An attitude of caution can help us avoid developing false beliefs that can lead to irrational decisions.

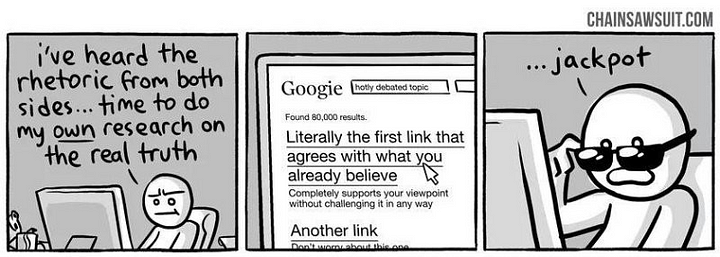

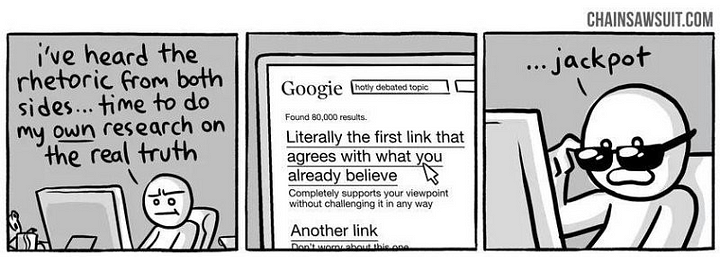

Junk Learning Source #3: Our Confirmation Bias Makes Us Progressively More Dumb

Copernicus published his thesis that the Earth revolves around the sun in 1543. Ninety years later, Galileo was arrested for agreeing with Copernicus. It took more than a hundred years for this model to be accepted — and 350 years for the Catholic church to officially accept it.

Confirmation bias is our tendency to only look for and believe information that supports what we already think, and to dismiss evidence to the contrary. And this example drives home just how powerful it is.

It also drives home another important lesson. A very small amount of disconfirming evidence can disprove a much larger body of confirming evidence. Consider how easy it must have been to believe that hat the sun revolves around the Earth — when for millennia all humans could see was the sun moving around us through the sky each day. Each incremental piece of evidence seemed to prove our original ideas right.

One of the biggest daily examples of confirmation bias involves our social media bubbles: We read the same sites, listen to the same friends (who agree with us!), and watch the same news over and over, which only confirms what we already believe. When we’re exposed to something that doesn’t fit our model of the world, we unconsciously either ignore it, minimize it, or attack it.

When we only hear opinions that confirm our beliefs, our learning is incremental at best. We learn the most by proving ourselves wrong, not by proving ourselves right. Many of the greatest thinkers of the 20th century independently came to this conclusion.

Karl Popper, one of the greatest philosophers of science, explained that what moves science forward is actually the discovery of disconfirming evidence.

Joseph Schumpeter, one of the greatest economists, showed that ideas don’t simply progress in a straight line forward. They grow through a process of creative destruction where old ideas are destroyed to make way for new paradigms.

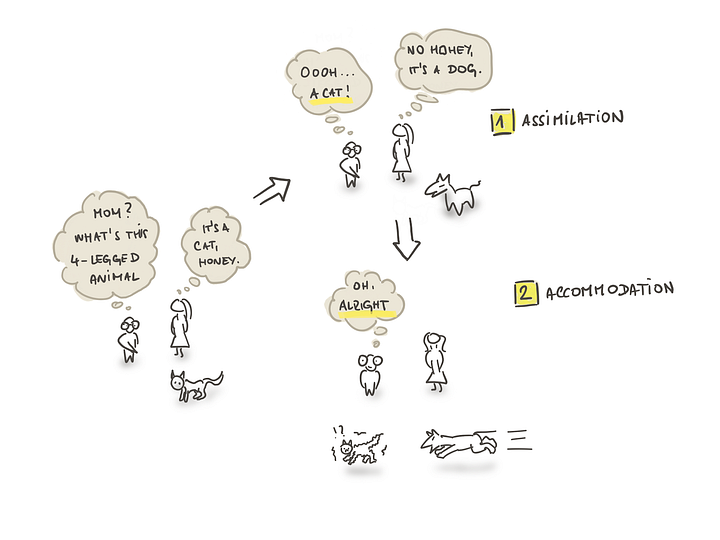

Jean Piaget, one of the greatest psychologists, showed that we grow our own knowledge the most when we transform our thinking to be able to accomodate external knowledge that doesn’t fit at first. In his model, when we are exposed to new information, we adapt to it in one of two ways:

- Assimilation — We use our existing base of knowledge to understand a new object or situation.

- Accommodation — We realize that our existing base of knowledge does not work, and needs to be changed in order to effectively deal with a new object or situation.

The following example shows the difference between assimilation and accommodation. Imagine, a three-year-old child who sees a cat for the first time and asks his mother, “Mommy? What’s that four-legged creature?” Smiling, she responds, “It’s a cat, honey.”

The next day, the boy is walking through his neighborhood with his mom, and he sees another four-legged creature, a dog. He excitedly turns to his mom and says, “Mommy… Mommy… oooh. Another cat!” Correcting him, she says, “No honey, it’s a dog.” The boy furrows his eyebrows in deep thought. He points to the dog and half asks half says, “doggy?!?!” His mom proudly replies, “That’s right! Good job.” and they continue their stroll.

What happened here?

The boy first tried to assimilate the new knowledge by fitting it into his existing schema. Cats have four legs. So do dogs. So they are the same.

When his mom corrected him, he went into deep thought because he needed to update his schema on what a cat was in order to understand what a dog was.

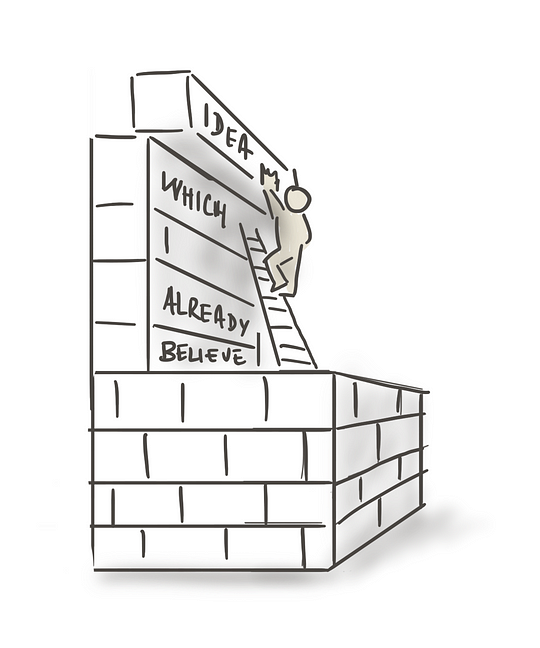

Popper, Schumpeter, and Piaget show that we stunt our growth when we ignore disconfirming evidence or distort evidence in order to make it assimilate with our existing knowledge. Focusing on learning what we already we believe is like building a really skinny wall that will topple over as it gets larger.

On the other hand, we go through a growth spurt when we actively search for disconfirming evidence and allow accomodation to happen.

It’s easier said than done because we hate to admit when we are wrong. Counteracting confirmation bias takes incredible psychic energy. It is the equivalent of doing strenuous physical exercise; it’s difficult, but worth it.

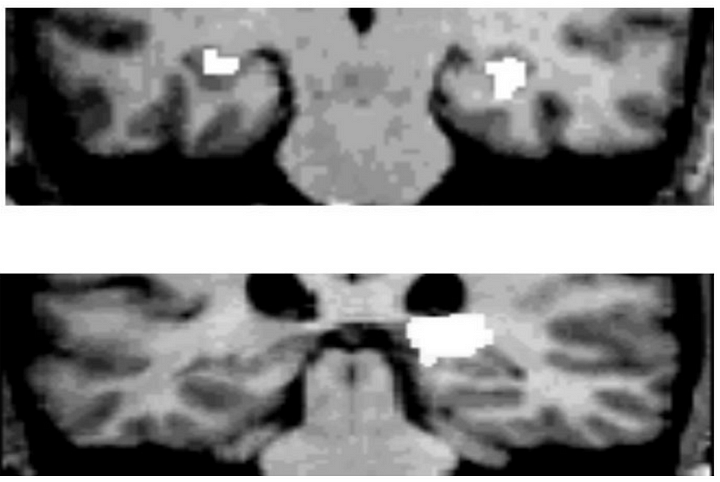

A fascinating study at the University Of Southern California shows just how unsettling it can be to go against our confirmation biases. In the study, participants had their brain scanned while they were presented with counterarguments to some of their political beliefs, such as:

- “Laws restricting gun ownership should be made more restrictive.”

- “Gay marriage should not be legalized.”

Amazingly, what the study found is that the same parts of the brain (for example, the amygdala) that respond to PHYSICAL threats also respond to INTELLECTUAL threats. In other words, reading about facts we disagree with can provoke the same sort of response we’d feel if we were being chased by a lion.

Matthew Inman, the creator of The Oatmeal, beautifully sums up how most of us protect our confirmation bias instead of attempting to get past it:

To some extent, we all walk around with rickety “knowledge buildings” surrounded by moats; whereas, if we let new, disproving information in, we could strengthen the building instead.

Lesson Learned: We need to identify and stress-test our most fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality— and learn how to handle the strong emotions that will come up when we do.

Junk Learning Source #4. We Trust the Wrong Ideas and the Wrong People

Humans are social learners. We watch someone do something and emulate it. If you’re a parent, you’ve seen this firsthand in your child. You say something or make a facial expression, and your little one copies it.

We often take the ability to mimic others for granted. But I see it as a superpower. In fact, it’s actually the superpower of a superhero in one of my favorite TV shows. This superhero is able to watch anyone do anything once and immediately master it:

But this superpower can go wrong if we copy the wrong things from the wrong people. Unfortunately, we do this all of the time as a result of the Halo Effect. This is a cognitive bias that makes us trust a person’s advice in one area of life simply because they are an expert in another area. Researcher Phil Rosenzweig breaks it down further in his book The Halo Effect (one of my favorite business books of all time):

…a tendency to make inferences about specific traits on the basis of a general impression. It’s difficult for most people to independently measure separate features; there’s a common tendency to blend them together.

It’s like buying a Lincoln car because Matthew McConaughey drives one in a Superbowl ad. It’s listening to a famous painter give his or her grand plan for re-engineering society. It’s trusting a scientist to tell us what’s wrong with our political system when that scientist has no experience in politics. It’s following the fashion advice of a professional athlete. It’s trusting the advice of a business celebrity who turned around a big company 10 years ago and wrote a bestselling book to help us grow our startup.

While these examples may seem obvious, the Halo Effect also shows up in much more subtle ways that are harder to recognize:

In the autumn of 2001, after the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush’s overall approval rating rose sharply. No surprise there, as the American public closed ranks behind its president. But the number of Americans who approved of President Bush’s handling of the economy also rose — from 47 percent to 60 percent. Now, whether or not you like Bush’s economic policies, there’s no reason to believe that his handling of the economy was suddenly better in the weeks after September 11. But it’s hard to keep these things separate: General approval of the president carried over to approval of a specific policy. The American public conferred a Halo on its president and made favorable attributions across the board. After all, it’s uncomfortable for many people to believe that their president might be good on issues of national security but ineffective on the economy — it’s far easier to think he’s about the same for both.

And ultimately, the example in the book that really drove home the point was the takedown of Jim Collins’ books Good To Great and Built To Last, two of the bestselling business books of all time. I had read each of these multiple times and looked upon them very highly. Collins and his team spent thousands and thousands of hours identifying:

- Companies that had outperformed their peers by a large margin over decades.

- The qualities that made them successful.

Yet, when Rosenzweig explored how the companies did after the books came out, the results are humbling:

Collins and Porras urge us not to “blindly and unquestioningly accept” their findings but ask that we subject their analysis to careful scrutiny. “Let the evidence speak for itself,” they implore. So let’s check the evidence. We may not be able to put companies in petri dishes and run experiments, but we can check how they fare over time. If the principles of Built to Last are indeed timeless and enduring explanations of performance, then we should expect these same companies to continue to perform well after the study ended. Conversely, if they can’t keep up their high performance, well, that would lend support to the view that these so-called timeless principles were due mostly to the Halo Effect — a glow cast by high performance rather than the cause of high performance.

So how well did the eighteen Visionary companies fare in the years after the study ended on December 31, 1990? All eighteen were still up and running in 2000, so at least they were built to last for another ten years. But as for performance, the record wasn’t so good. Using data from Compustat, I looked at total shareholder return for each company for the five years after the study ended, 1991– 1995. The results? Out of seventeen companies, chosen specifically because they had outperformed the market by a factor of 15 for more than sixty-four years, only eight outperformed the S& P 500 market average; the other nine didn’t even keep up.

An analysis of Good To Great companies after the book came out had similar results.

We fall for the Halo Effect in our professional lives when we buy books or get mentors and don’t discount that what worked in their industry, in the past, at their size company, in one specific department many not work for us too.

We also fall for the Halo Effect when we have a success and generalize it too far like I did earlier in my career when I attributed our success to personal genius rather than an economic cycle.

Lesson Learned: As a result of reading The Halo Effect, I’ve become much more suspicious of listening to celebrity experts in any field. Instead, now whenever I look at who to emulate, I specifically look for people who have experienced success over and over not because of luck or celebrity, but because of skill. In my experience, many of these individuals are not celebrities. Then, I carefully experiment with their advice to see if it will transfer to my context.

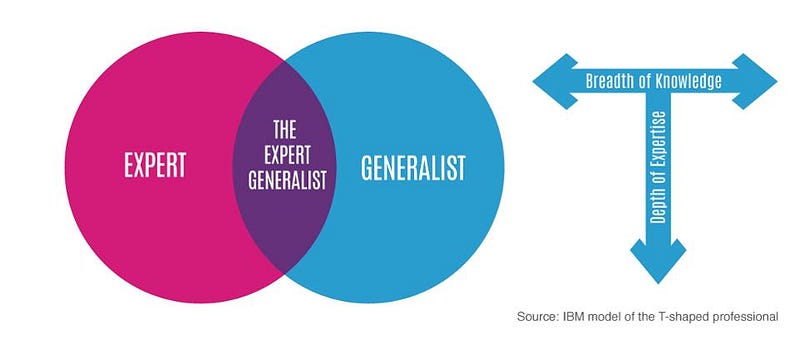

Junk Learning Source #5. Over-specialization limits our ability to learn across disciplines

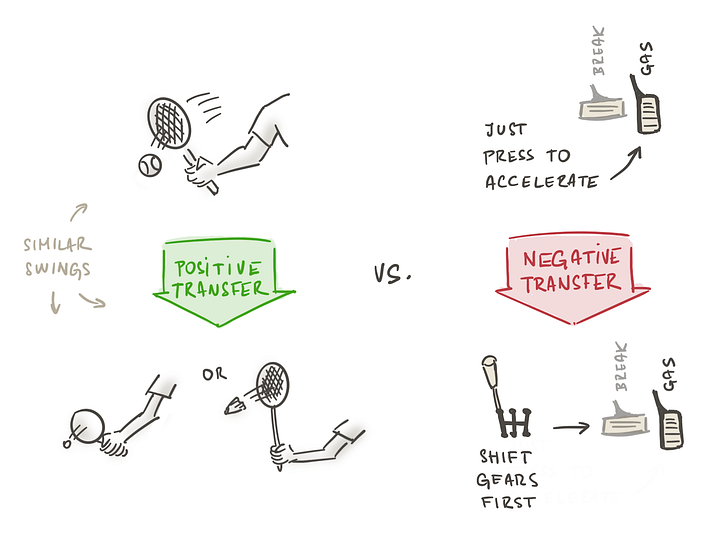

In other articles, I’ve written about learning transfer. This is our ability to learn a concept in one domain and then apply it to another.

In learning science, positive transfer is when learning something makes it more likely that we will transfer our knowledge. Learning addition and subtraction, for example, help children then learning multiplication and division. Learning to play one racket sport like tennis can help others learn to play other racket sports like badminton and table tennis.

Negative transfer, on the other hand, is when learning something hinders learning transfer.If you’ve ever switched from driving an automatic transmission to a manual one, you’ve had to unlearn the habit of simply pressing the gas, and get used to engaging the clutch and shifting gears before accelerating. If your first language is a European one like Spanish, French, or German, you’ve had to get over the fact that in English, nouns have no gender. Or consider the all-too-familiar case of a software password. Just when you finally memorize one, you get asked to create a new one. Do this a few times, and it’s hard to remember which password to key in because you keep getting them confused.

Scarily, research in the field of expert performance shows that these negative transfer effects can:

“…get worse as higher levels of expertise are reached, as the acquired knowledge becomes increasingly specialized. This is because the perceptual chunks, which act as the condition part of productions, become more selective…

Interestingly, the author’s suggestions to this challenge parallel our approach of using the trunk technique:

If this analysis is correct, and keeping in mind that it is difficult to predict what skills will be required two or three decades from now, the best option seems to supplement the teaching of specific knowledge with the teaching of metaheuristics that are transferable (Grotzer & Perkins, 2000; Simon, 1980). These may include strategies about how to learn, how to direct one’s attention in novel domains, and how to monitor and regulate one’s limited resources, such as small STM [short-term memory] capacity and slow learning rates.”

Lesson Learned: Being too specialized can hurt future learning if done alone. Supplement by spending more of your time learning fundamental knowledge that doesn’t change. This is why we created the Mental Model Club.

Take Action: Strengthen Your Brain Instead of Damaging It

Just as learning what junk food is can help us eat healthier, learning how NOT to learn can help us learn faster and better. Remember these junk learning sources, and their solutions, so you can recognize and avoid them.

1. Our “facts” are expiring and we don’t even know it.

Look for information that actually increases in value over time. When it comes to knowledge, think like an investor, not a consumer.

2. A little knowledge is dangerous.

Realize you only know a little bit. Assume ignorance to avoid developing false beliefs that can lead to irrational decisions.

3. Our confirmation bias makes us progressively more dumb.

Identify and stress-test your most fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality — and learn how to handle the strong emotions that will come up when you do.

4. We too often trust the wrong ideas and the wrong people.

Remember that celebrities are often not experts at anything except their specific field of celebrity (music, acting, a sport, etc.). Be super careful about whom and what you choose to emulate.

5. Over-specialization limits our ability to learn across disciplines

Specialized knowledge can hurt future learning. Instead, spend most of your time learning fundamental knowledge that doesn’t change such as mental models.

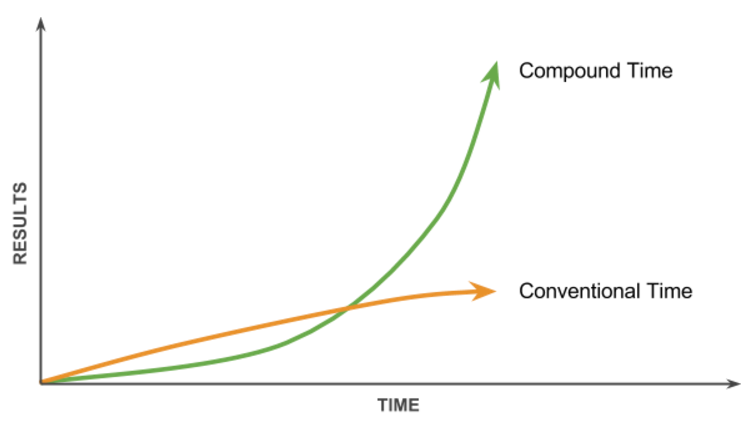

Knowledge doesn’t innately compound to make us smarter. In fact, as we learned in this article, it is possible for people to actually become dumber as they put in more learning time.

Here’s How to Master Mental Models

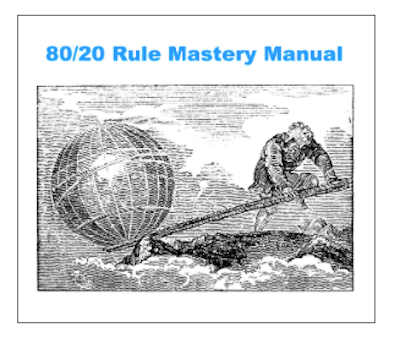

In our Mental Model Club, we help you learn the most fundamental mental models and principles that will last forever and that you can apply in ever area of your life. Each month, you receive a 15,000-word Mastery Manual that condenses dozens of books into a how-to guide with workbook and resource list. By joining now, you will get our best Mastery Manual.

Why Constant Learners All Embrace the 5-Hour Rule

Benjamin Franklin did this 1 hour a day, 5 hours a week. Why you should do it too.

At the age of 10, Benjamin Franklin left formal schooling to become an apprentice to his father. As a teenager, he showed no particular talent or aptitude aside from his love of books.

When he died a little over half a century later, he was America’s most respected statesman, its most famous inventor, a prolific author, and a successful entrepreneur.

What happened between these two points to cause such a meteoric rise?

The answer to this question is a success strategy that we can all use, and increasingly must use for our career, business and life.

The five-hour rule

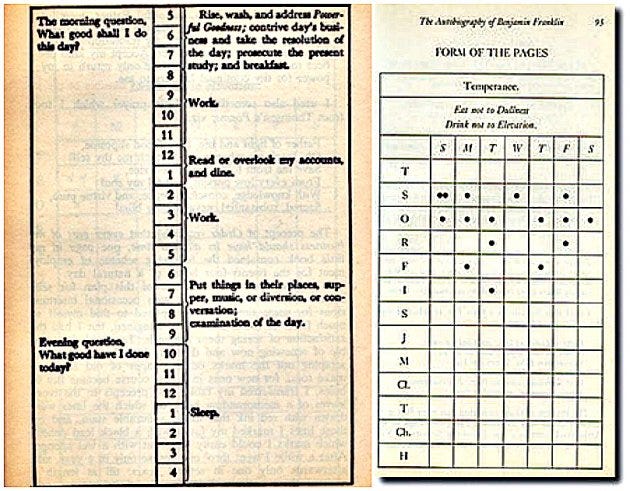

Throughout Ben Franklin’s adult life, he consistently invested roughly an hour a day in deliberate learning. I call this Franklin’s five-hour rule: one hour a day on every weekday.

Franklin’s learning time consisted of:

- Waking up early to read and write

- Setting personal-growth goals (i.e., virtues list) and tracking the results

- Creating a club for “like-minded aspiring artisans and tradesmen who hoped to improve themselves while they improved their community”

- Turning his ideas into experiments

- Having morning and evening reflection questions

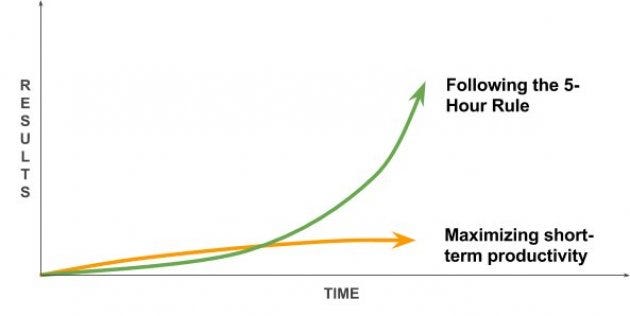

Every time that Franklin took time out of his busy day to follow his five-hour rule and spend at least an hour learning, he accomplished less on that day. However, in the long run, it was arguably the best investment of his time he could have made.

Franklin’s five-hour rule reflects the very simple idea that, over time, the smartest and most successful people are the ones who are constant and deliberate learners. And at the core of their learning is reading:

- Warren Buffett spends five to six hours per day reading five newspapers and 500 pages of corporate reports.

- Bill Gates reads 50 books per year.

- Mark Zuckerberg reads at least one book every two weeks.

- Elon Musk grew up reading two books a day, according to his brother.

- Oprah Winfrey credits books with much of her success: “Books were my pass to personal freedom.”

- Arthur Blank, co-founder of Home Depot, reads two hours a day.

- Dan Gilbert, self-made billionaire and owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers, reads one to two hours a day.

So what would it look like to make the five-hour rule part of our lifestyle?

First, make time for learning

To find out, we need look no further than chess grandmaster and world-champion martial artist Josh Waitzkin. Instead of squeezing his days for the maximum productivity, he’s actually done the opposite. Waitzkin, who also authored The Art of Learning, purposely creates slack in his day so he has“empty space” for learning, creativity, and doing things at a higher quality.Here’s his explanation of this approach from a recent Tim Ferriss podcast episode:

“I have built a life around having empty space for the development of my ideas for the creative process. And for the cultivation of a physiological state which is receptive enough to tune in very, very deeply to people I work with … In the creative process, it’s so easy to drive for efficiency and take for granted the really subtle internal work that it takes to play on that razor’s edge.”

Adding slack to our day allows us to:

- 1. Plan out the learning. This allows us to think carefully about what we want to learn. We shouldn’t just have goals for what we want to accomplish. We should also have goals for what we want to learn.

- 2. Deliberately practice. Rather than doing things automatically and not improving, we can apply the proven principles of deliberate practice so we keep improving. This means doing things like taking time to get honest feedback on our work and practicing specific skills we want to improve.

- 3. Ruminate. This helps us get more perspective on our lessons learned and assimilate new ideas. It can also help us develop slow hunches in order to have creative breakthroughs. Walking is a great way to process these insights, as shown by many greats who were or are walking fanatics, from Beethoven and Charles Darwin to Steve Jobs and Jack Dorsey. Another powerful way is through conversation partners.

- 5. Set aside time just for learning. This includes activities like reading, having conversations, participating in a mastermind, taking classes, observing others, etc.

- 6. Solve problems as they arise. When most people experience problems during the day, they sweep them under the rug so that they can continue their to-do list. Having slack creates the space to address small problems before they turn into big problems.

- 7. Do small experiments with big potential payoffs. Whether or not an experiment works, it’s an opportunity to learn and test your ideas.

Next, read the best books in the world

Want to read the most-recommended books by top leaders like Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and Elon Musk?

My team and I went through 460+ book recommendations of top CEOs and entrepreneurs, crunched the data, and found the six most recommended books.

To help you follow the 5-hour rule, you can access the most recommended books here for free.

Finally, read faster

The final problem now is that it could take you years of focused reading just to get through these hundreds of book recommendations.

There is a solution though.

Imagine if you could read one book a day?

And…get the best ideas from each book immediately?

This is possible.

The reality is that the value of a book is not evenly distributed. It is likely that you will get 80% of the true value from only a few pages.

That often means that a lot of reading time is wasted.

This is where book summaries come in.

But, as much as I love most book summaries out there, they typically have two problems:

- They just aren’t designed to help you apply your knowledge into real life situations, so that you can get results.

- They don’t show how the books’ ideas connects to other books.

So, after reading thousands of books, and talking with the best learning experts in the world, I developed my own unique learning system that is essentially book summaries on steroids.

Here’s how I developed this learning system, step-by-step:

- I pick the best books in the world to read. (I pull from the great thinkers, leaders, and entrepreneurs of all time — from self-made billionaires Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett, and Ray Dalio — to leading academics and thinkers like Nassim Taleb and Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman.)

- Then, I take detailed notes of the best ideas

- Next, I connect those ideas to all of the other best ideas I’ve learned

- Finally, I create simple exercises to help apply these ideas.

In other words, instead of just summarizing books, I extract their most valuable gems, put them in context, and make them actionable.

That is how you can read one book in one day!

If you want to read the consume the best ideas in the world, let me save you time.

Self-Made Billionaire: There Are Three Levels Of Reality, And Most People Are Stuck In Level One, But They Have No Idea

The brutal truth is that most people aren’t even aware of Level 2 or 3

One commonality of great thinkers, CEOs, and entrepreneurs throughout history is that they see reality on a deeper level. This helps them figuratively play chess while everyone else plays checkers.

This realization slowly came to me as I spent thousands of hours over the last few years reading, watching, and listening to everything from many of history’s wisest business leaders, from Charlie Munger, Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Warren Buffett, and Jeff Bezos to Thomas Edison and Benjamin Franklin (all of whom I have written about).

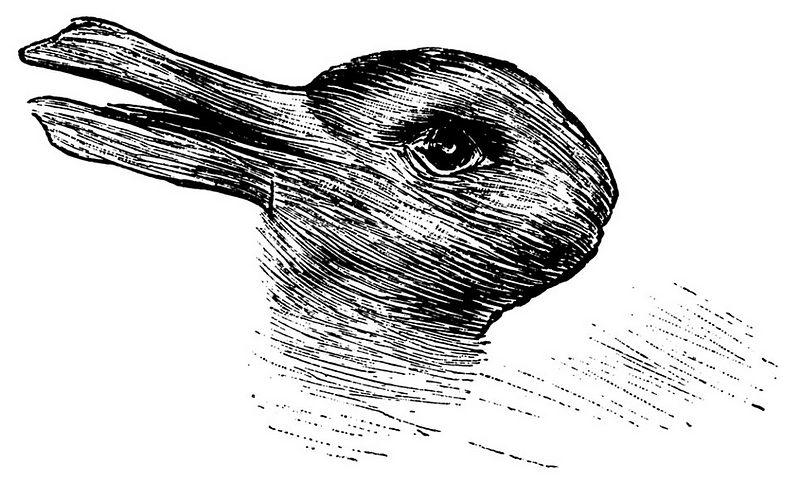

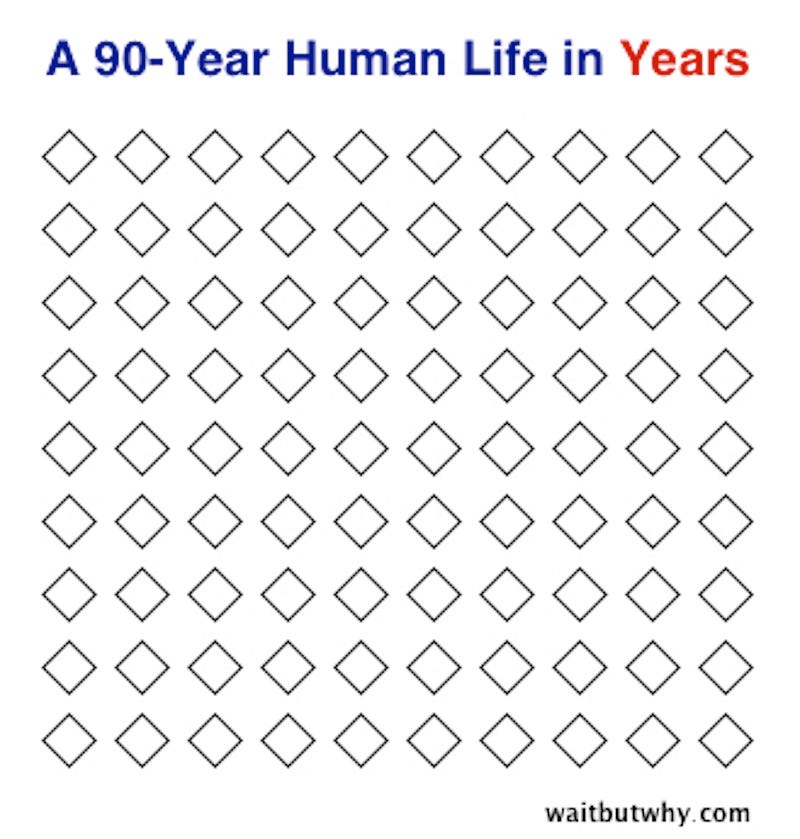

Over and over, I thought I understood their words, and then later, when I revisited them, I realized there was a whole other layer I had missed. The experience was like looking at this image below, seeing only one thing and then realizing it is both a picture of a duck and a bunny.

See it?

This all brings me to self-made billionaire, entrepreneur, investor, and polymath Ray Dalio. Dalio is the founder of Bridgewater Associates, the largest hedge fund in the world, and his approach to and results from uncovering and using deep principles and mental models is unparalleled. Over the last 40 years, Dalio has meticulously identified and stress-tested a set of universal, success principles, and then created detailed step-by-step systems that his 1,500-person team uses to make management and investment decisions. This year, he effectively open-sourced everything with the release of his book, Principles: Life and Work.

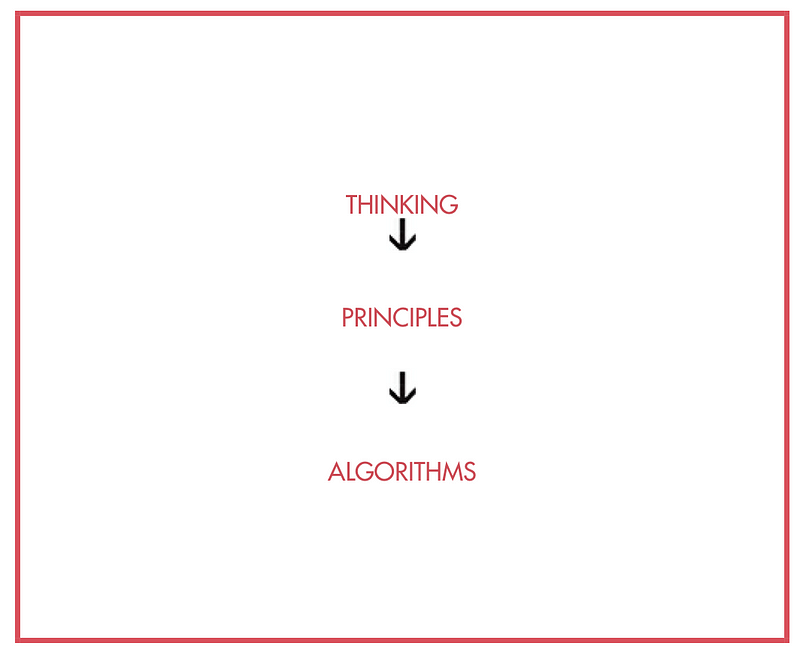

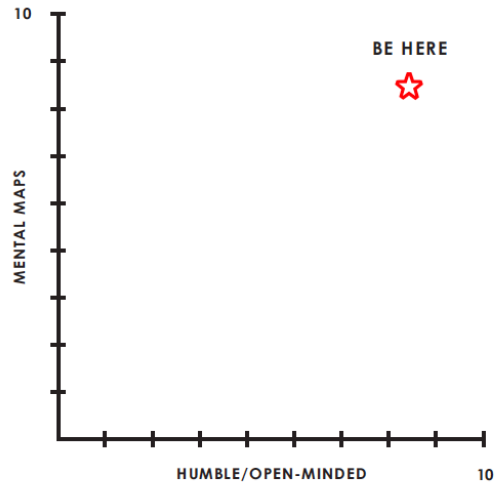

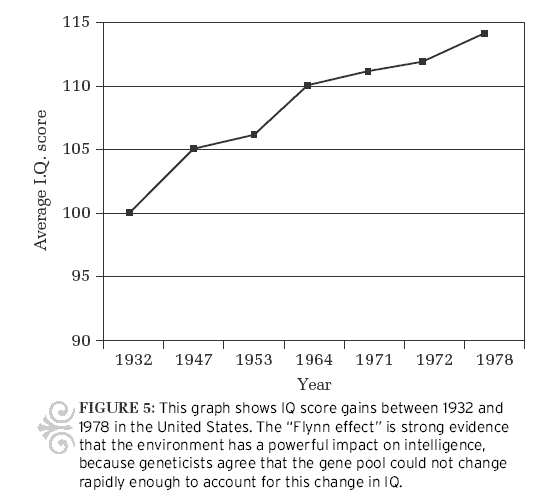

This chart below from Dalio’s book is like the duck/bunny image. On one level, it’s a simple chart like any other chart. On another level, it’s profound and speaks to the three levels of reality that Dalio sees.

Source: Principles: Life and Work by Ray Dalio

Understanding these three levels of reality is critical because the better you build a map of how reality works, and the more you’re open to improving that map, the more successful you’ll be.

Let’s dive into Dalio’s three levels of reality…

Reality Level 1: Getting Stuff Done

Most people operate in this realm. The output of a good sales call is a closed sale. The outcome of a good meeting is the resolution of a specific problem. Conversely, a bad sales call is one that doesn’t result in a new customer. A bad meeting is one that decides nothing.

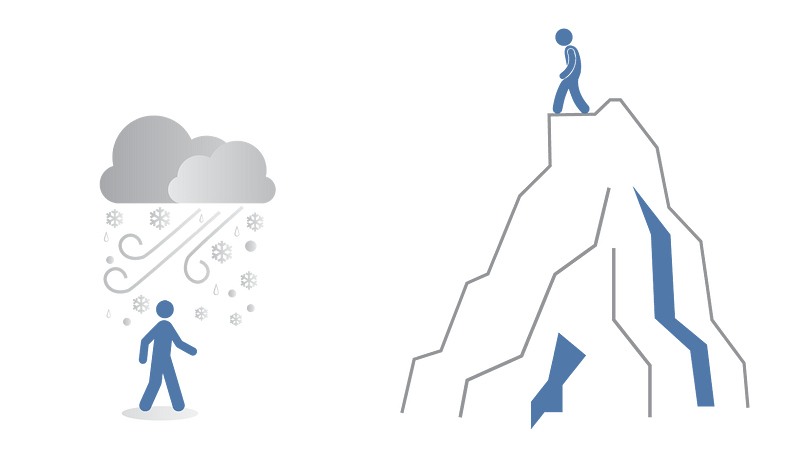

This level of reality is essentially about getting stuff done: creating a to-do list from most important to least important and then kicking butt right on down the list. Dalio calls this layer of reality the blizzard because lots of things are constantly coming at you from different directions, and it’s hard to get clarity on what really matters.

Dalio’s book is not written on this level. Most books are.

Reality Level 2: Principles

To people like Dalio, the value of an activity isn’t just its immediate result, but also the underlying principles at play. The principles you learn in any situation are often more valuable than the immediate result, because you can apply them for the rest of your life across all areas to make better decisions.

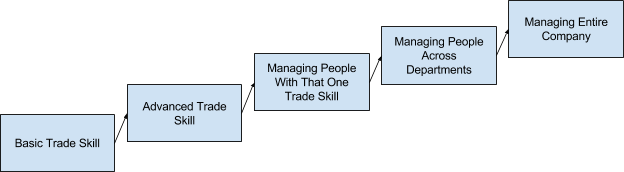

For example, let’s say you’re a salesperson. At Level 2, each sales call is an opportunity to learn about related principles on multiple levels:

As you move down toward fundamental mental models of what selling is and how it works, you gets closer to principles that are more timeless and universal.

Once you reach the “timeless and universal” level, you can apply a principle or mental model to exponentially more situations. And this is the key here. Once you reach an understanding of a mental model, you have a tool that can apply in many situations now and in the future to help you be more efficient, get more done, make better decisions, have better relationships, become more successful, and become more impactful.

Let’s take Stephen Covey’s fundamental principle of ‘Seek first to understand and then to be understood’ as an example. This principle can help you sell a product, but it can also help you be a better parent, have a happier marriage, enjoy deeper friendships, and get along with people of different cultures, faiths, and political backgrounds. If you’re interested in learning more about the value of fundamental principles and mental models, I wrote about it in How To Tell If Someone Is Truly Smart Or Just Average.

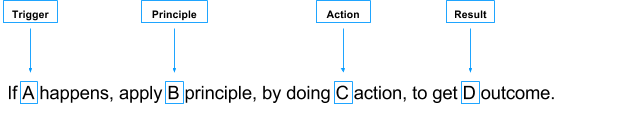

So let’s say you have a sales call where the prospect doesn’t buy from and become a customer. If you operated from Level 1 of reality, this call would be a painful waste of time. To Dalio, at Level 2, it would be a learning opportunity because of his following core principle:

“Pain + Reflection = Progress.”

As he explains:

“There’s so much more that you can learn from mistakes because they give you a loud signal. Rewards keep you doing the same things, and so you don’t grow from successes… Mistakes, if you can deal with them the right way, with reflection is where the growth comes from.”

Dalio’s approach is counterintuitive on two levels. First, society typically judges success by first-order results (i.e., immediate sales), not second-order ones (i.e., improving the system that makes sales). Secondly, our natural reaction to pain is to resist it and react emotionally. Dalio has built systems, tools, and habits that help him move toward pain, react logically and objectively, and engage in thoughtful disagreement rather than arguments, which I’ll explain later in the article. While we all intellectually understand that we can learn from pain, I’ve never come across someone who is as systematic and committed to it as Dalio.

While Level 1 of reality is a blizzard, Level 2 is more like standing on a mountaintop in a clear sky looking down at the blizzard.

And because you have this wider aperture on life, you’re able to see connections more naturally. Dalio explains:

“With time and experience, I came to see each encounter as ‘another one of those’ that I could approach more calmly and analytically, like a biologist might approach an encounter with a threatening creature in the jungle: first identifying its species and then, drawing on his prior knowledge about its expected behaviors, reacting appropriately. When I was faced with types of situations I had encountered before, I drew on the principles I had learned for dealing with them. But when I ran into ones I hadn’t seen before, I would be painfully surprised. Studying all those painful first-time encounters, I learned that even if they hadn’t happened to me, most of them had happened to other people in other times and places, which gave me a healthy respect for history, a hunger to have a universal understanding of how reality works, and the desire to build timeless and universal principles for dealing with it.”

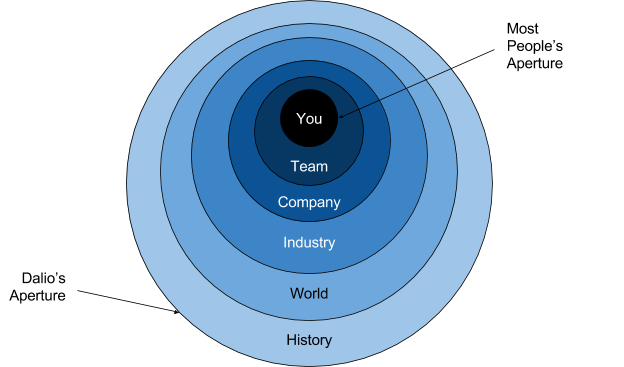

While we all learn from our experiences at some level, what separates Dalio is two things. First, he doesn’t just pull from his own seven decades of personal experience. He attempts to pull from all experiences of recorded history. This approach gives him a tremendous advantage as investor because some financial cycles happen every few months or few years, but other cycles only happen every few decades or every century. With Dalio’s wider lens, he can see those patterns. Our own personal experiences are a drop in the ocean of humanity’s experiences through all time.

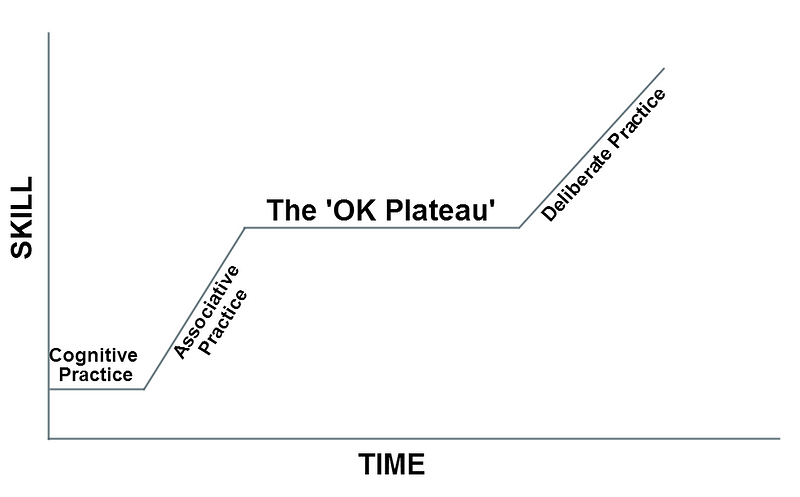

Secondly, he doesn’t just learn from his experience reactively and unconsciously. He is extremely deliberate. This is important because of the OK Plateau — most people learn quickly in new situations, but soon plateau after they’re “good enough” and never get better with more experience. This has been heavily studied in the professional world, and it’s evident in our daily lives. Has driving more made you a better driver? Has typing more made you a better typist?

I go into what I mean by “deliberate” in Level 3, as this is where the magic happens.

Reality Level 3: Algorithms

This is the point at which Dalio’s teachings started to blow my mind. It’s also the level which causes the most controversy in the media. Dalio has systematically taken his principles and turned them into algorithms in computers that he uses to make better investing and people decisions.

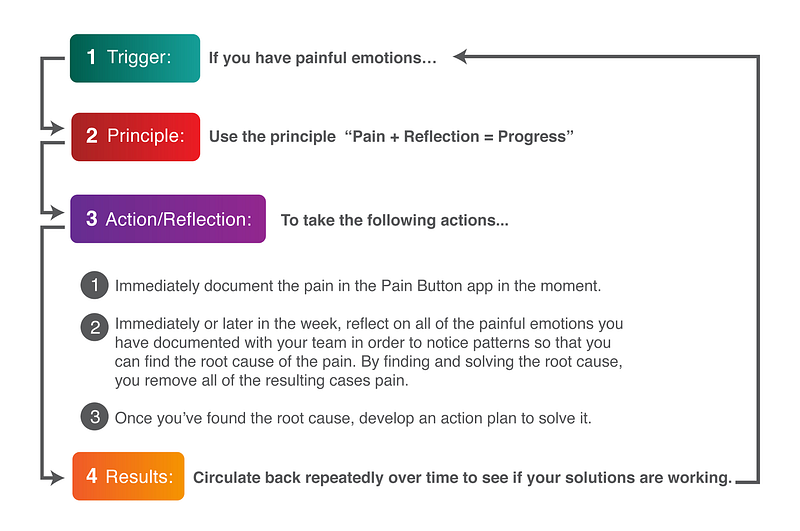

What does that mean in practice? For one, Dalio’s company, Bridgewater, has developed several apps that employees use to make better decisions. One of them is called the Pain Button. Here’s how it works:

In building these apps and collecting the data from them, Bridgewater may have built the largest database of team interaction ever in the history of mankind.

Bridgewater, of course, doesn’t just focus on employee emotions, but also on their investments. Starting in the 1970s, Dalio created investment algorithms and turned them into code. Over time, he improved the code in two ways:

- As he and his team learned more principles, they turned those into algorithms, and then turned those into code.

- He and his team stress-tested the algorithms using historical data. In other words, he fed historical data into the program. Then, he let his algorithm run loose to see what decisions it would’ve made in that historical context. With the gift of hindsight, he was able to see the actual amount of money the algorithm would’ve made or lost without risking a penny.

- With the results from stress-testing, he and his team refined the principles, algorithms, and code.

As Bridgewater got better and better results, they trusted the system more and more, and started using it to help make real-world investment decisions. Over time, the algorithms have become effective enough for Bridgewater to trust its decisions 98 percent of the time.

In short, at Level 3, Dalio doesn’t just let the general principles of Level 2 remain general principles. He systematically understands how the principles interact with each other to create specific results in the world:

“Visualizing complex systems as machines, figuring out the cause-effect relationships within them, writing down the principles for dealing with them, and feeding them into a computer so the computer could ‘make decisions’ for me all became standard practices.”

Dalio’s approach sparks controversy among many: “What about the chaos and randomness of life? You can’t reduce complex decisions or dynamics between people into engineering problems!” This is where it’s important to understand that Dalio doesn’t claim to have a perfect machine that does everything perfectly without humans. Dalio views his machine as a trusted advisor to human decision-making.

Naturally, Dalio has immense financial and human resources to build his machines. But we can still learn from and emulate his approach. For example, Dalio’s approaches have had a huge impact on me in two ways:

- After reading his work, I realized I had a pervasive pattern of ignoring painful problems or only dealing with them once they blew up. So, I started logging problems, doing a weekly root cause analysis conversation with my wife, with myself, and with our team.

- Rather than just being a writer, our company created an idea machine where we systematically found principles of how quality ideas are created and how they spread. We stress-tested those principles with lots of experimentation, and then built systems and tools to help the process. Starting with very little profile and no list, my writing has been seen nearly 15 million times across platforms in the last 3 years with just a few dozen articles.

Putting It All Together: Rethinking Productivity

We all just have 24 hours in a day. Yet some people move much closer toward their goals than others. In other words, they get more value from each experience they have. The learning value that Dalio gets from every moment is exponentially greater than the average person.

In order to unlock this value, Dalio focuses on three levels of reality while most people focus on just one. He also thinks about his time differently. Rather than just focusing the day around getting stuff done, throughout his career he has focused on constant and deliberate learning. I call this tendency for many of the busiest, most successful leaders to spend at least 5 hours or more per week learning the 5-hour rule.

Dalio’s approach means he gets less done in a day, but gets drastically more done in his life. This happens because the value of operating on Levels 2 & 3 compound over time. After 40 years of living at all three levels of reality, Dalio has built up an incredibly powerful legacy:

- Core principles he has shared in his book Principles, which is reverberating throughout society to millions of people.

- An investing machine that can be run without him that has generated tens of billions of dollars so far and likely hundreds of billions in the future.

- A management machine that has helped Bridgewater scale to 1,500-plus employees that any company could use.

When most people ask themselves how they can take their life to the next level, they often think about new skills they could start or bad habits they could stop. This is Level 1 thinking. It works, but only so far.

By understanding the different levels of reality, we can all break through the glass ceilings in our life and realize more of our latent potential and leave a legacy.

Want to get started with Dalio’s approach?

In order to use principles and mental models, we must first collect and learn how to use the most valuable ones. I’ve learned from personal experience that it literally takes years to develop true mastery of these. Therefore, I created two resources for you:

Resource #1: Free Mental Model Course (For Newbies)

If you’re just learning about mental models for the first time, my free email course will help you get started. My team and I have spent dozens of hours creating it. Inside, you’ll learn the models that these billionaires use to make business and investing decisions — tools you can apply immediately to your life and business. You’ll also learn how to naturally use these models in your everyday life.

Sign up for the free mini-course here >>

Resource #2: Mental Model Of The Month Club (For Those Who Want Mastery)

If you’re already convinced of the power of mental models and want to deliberately set about mastering them, then this resource is for you. It’s the program I wish I’d had when I was just getting started with mental models.

Here’s how it works:

- Every month, you’ll master one new mental model.

- We’ll focus on the most powerful and universal models first.

- We’ll provide you with a condensed and simple Mastery Manual (think: Cliff’s Notes) to help you deeply understand the model and integrate it into your life.

Each master manual includes:

- A 101 Overview of the mental model (why it’s important, how it works, its vocabulary, etc.)

- An Advanced Overview that includes a more nuanced explanation.

- Hacks you can use immediately to apply that mental model to every area of your life and career. These hacks are based on my personal experience and are crowdsourced as well.

- Exercises and templates you can use on a daily basis to integrate the lessons in the manual and achieve maximum results in your life.

- A Facebook community where you can meet other mental model collectors and learn from one another.

To learn more about the program or to sign up, visit the Mental Model Of The Month Overview page.

Bill Gates, Warren Buffett And Oprah All Use The 5-Hour Rule

Article featured: Inc., Time, Observer, Business.com, Life Hacker, & Yahoo.

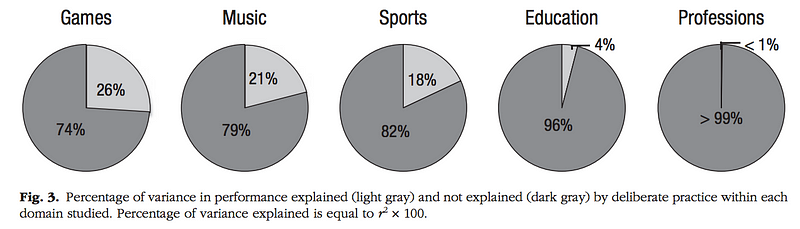

In the article “Malcolm Gladwell got us wrong”, the researchers behind the 10,000-hour rule set the record straight: different fields require different amounts of deliberate practice in order to become world class.

If 10,000 hours isn’t an absolute rule that applies across fields, what does it really take to become world class in the world of work?

Over the last year, I’ve explored the personal history of many widely-admired business leaders like Elon Musk, Oprah Winfrey, Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and Mark Zuckerberg in order to understand how they apply the principles of deliberate practice.

What I’ve done does not qualify as an academic study, but it does reveal a surprising pattern.

Many of these leaders, despite being extremely busy, set aside at least an hour a day (or five hours a week) over their entire career for activities that could be classified as deliberate practice or learning.

I call this phenomenon the 5-hour rule.

How the best leaders follow the 5-hour rule

For the leaders I tracked, the 5-hour rule often fell into three buckets: reading, reflection, and experimentation.

1. Read

According to an HBR article, “Nike founder Phil Knight so reveres his library that in it you have to take off your shoes and bow.”

Oprah Winfrey credits books with much of her success: “Books were my pass to personal freedom.” She has shared her reading habit with the world via her book club.

These two are not alone. Consider the extreme reading habits of other billionaire entrepreneurs:

- Warren Buffett spends five to six hours per day reading five newspapers and 500 pages of corporate reports.

- Bill Gates reads 50 books per year.

- Mark Zuckerberg reads at least one book every two weeks.

- Elon Musk grew up reading two books a day, according to his brother.

- Mark Cuban reads more than 3 hours every day.

- Arthur Blank, co-founder of Home Depot, reads two hours a day.

- Billionaire entrepreneur David Rubenstein reads six books a week.

- Dan Gilbert, self-made billionaire and owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers, reads one to two hours a day.

Want to find the time to read? Sign up for the free webinar here.

2. Reflect

Other times, the 5-hour rule takes the form of reflection and thinking time.

AOL CEO Tim Armstrong makes his senior team spend four hours per week just thinking. Jack Dorsey is a serial wanderer. LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner schedules two hours of thinking time per day. Brian Scudamore, the founder of the 250 million-dollar company, O2E Brands, spends 10 hours a week just thinking.

When Reid Hoffman needs help thinking through an idea, he calls one of his pals: Peter Thiel, Max Levchin, or Elon Musk. When billionaire Ray Dalio makes a mistake, he logs it into a system that is public to all employees at his company. Then, he schedules time with his team to find the root cause.Billionaire entrepreneur Sara Blakely is a long-time journaler. In one interview, she shared that she has over 20 notebooks where she logged the terrible things that happened to her and the gifts that have unfolded as a result.

If you want to be in to company of others who reflect on what they’re learning with each other, join this Facebook group.

3. Experiment

Finally, the 5-hour rule takes the form of rapid experimentation.

Throughout his life, Ben Franklin set aside time for experimentation, masterminding with like-minded individuals, and tracking his virtues. Google famously allowed employees to experiment with new projects with 20% of their work time. Facebook encourages experimentation through The largest example of experimentation might be Thomas Edison. Even though he was a genius, Edison approached new inventions with humility. He would identify every possible solution and then systematically test each one of them. According to one of his biographers, “Although he understood the theories of his day, he found them useless in solving unknown problems.”

He took the approach to such an extreme that his competitor, Nikola Tesla, had this to say about the trial-and-error approach: “If [Edison] had a needle to find in a haystack, he would not stop to reason where it was most likely to be, he would proceed at once with the feverish diligence of the bee to examine straw after straw until he found the object of his search.”

The power of the 5-hour rule: improvement rate

People who apply the 5-hour rule in the world of work have an advantage.The idea of deliberate practice versus just working hard is often confused. Also, most professionals focus on productivity and efficiency, not improvement rate. As a result, just five hours of deliberate learning a week can set you apart.

Billionaire entrepreneur Marc Andreessen poignantly talked about improvement rate in a recent interview. “I think the archetype/myth of the 22-year-old founder has been blown completely out of proportion… I think skill acquisition, literally the acquisition of skills and how to do things, is just dramatically underrated. People are overvaluing the value of just jumping into the deep-end of the pool, because like the reality is that people who jump into the deep end of the pool drown. Like, there’s a reason why there are so many stories about Mark Zuckerberg. There aren’t that many Mark Zuckerbergs. Most of them are still floating face down in the pool. And so, for most of us, it’s a good idea to get skills.”

Later in the interview he adds, “The really great CEOs, if you spend time with them, you would find this to be true of Mark [Zuckerberg] today or of any of the great CEOs of today or the past, they are really encyclopedic of their knowledge of how to run a company, and it’s very hard to just intuit all of that in your early 20s. The path that makes much more sense for most people is to spend 5–10 years getting skills.”

We should look at learning like we look at exercise.

We need to move beyond the cliche, “Life-long learning is good,” and think more deeply about what the minimum amount of learning the average person should do per day in order to have a sustainable and successful career.

Just as we have minimum recommended dosages of vitamins, steps per day, and aerobic exercise for leading a healthy life physically, we should be more rigorous about how we as an information society think about the minimum doses of deliberate learning for leading a healthy life economically.

The long-term effects of NOT learning are just as insidious as the long-term effects of not having a healthy lifestyle. The CEO of AT&T makes this point loud and clear in an interview with the New York Times; he says that those who don’t spend at least 5 to 10 hours a week learning online “will obsolete themselves with technology.”

Interested in applying the 5-hour rule to your life?

Bottom line: the busiest, most successful people in the world find at least an hour to learn EVERYDAY. So can you!

There are just three steps you need to take in order to create your own learning ritual:

- Find the time for reading and learning even if you are really busy and overwhelmed.

- Stay consistent on using that ‘found’ time without procrastinating or falling prey to distraction.

- Increase the results you receive from each hour of learning by using proven hacks that help you remember and apply what you learn.

Over the last three years, I’ve researched how top performers find the time, stay consistent, and get more results. There was too much information to fit in one article, so I spent dozens of hours and created a free masterclass to help you master your learning ritual too!

Sign up for the free Learning How To Learn webinar here.

How To Tell If Someone Is Truly Smart Or Just Average

Have you ever noticed how some of the world’s most successful entrepreneurs and leaders see reality in a fundamentally different way? When they talk, it’s almost as if they’re speaking a different language.

Just look at this interview where Elon Musk describes how he understands cause and effect:

“I look at the future from the standpoint of probabilities. It’s like a branching stream of probabilities, and there are actions that we can take that affect those probabilities or that accelerate one thing or slow down another thing. I may introduce something new to the probability stream.”

Unusual, right? One writer who interviewed Musk describes his mental process like this:

“Musk sees people as computers, and he sees his brain software as the most important product he owns — and since there aren’t companies out there designing brain software, he designed his own, beta tests it every day, and makes constant updates.”

Musk’s top priority is designing the software in his brain. Have you ever heard anyone else describe their life that way?

Self-made billionaire Ray Dalio is no less “weird.” In his book, Principles, he describes how he sees reality: “Nature is a machine. The family is a machine. The life cycle is like a machine.” Dalio’s company, the largest hedge fund in the world, records every conversation (meeting or phone call) inside the company and has built several custom apps that allow any employee to rate any other employee in real time. The data is then added to profiles that each employee can see and is subsequently fed into an artificial intelligence system that helps employees make better decisions.

Dalio also describes his day in much different terms than you would expect from a CEO:

“I’m very much stepping back. I’m much more likely to go to what I describe as a higher level. There’s the blizzard that everyone is normally in, and that’s where they’re caught with all of these things coming at them. And I prefer to go above the blizzard and just organize.”

Charlie Munger uses a “cognitive bias checklist” before making investment decisions to ensure he properly applies the correct mental models. Warren Buffett uses decision trees. Jeff Bezos thinks of Amazon as being at Day One even though it’s been around more than 20 years.

What’s going on here? Are these just the idiosyncrasies of geniuses, or do these entrepreneurs employ a way of using their brain that we too could learn from in order to become smarter, more successful, and more impactful ourselves?

How I Learned to Think Like the World’s Best and Brightest

Over the years, as I’ve studied all of the above entrepreneurs, I’ve also aggressively applied their teachings. Even if I didn’t understand what they were saying at first, I took their advice on faith.

I’ve applied Ray Dalio’s root-cause analysis approach to our company. Now, throughout the week, everyone on our team logs any problems they’re facing. Then, we have a weekly phone call to discuss our biggest, recurring problem and its possible root cause.

I’ve applied Charlie Munger’s approach to mental models and collected thousands of pages of notes in order to create in-depth briefs on each model.

I’ve applied Musk’s probabilistic thinking to major decisions by listing out all of the potential decisions I could make and then assigning a cost, potential value, and probability to each one.

I’ve also created an experimentation engine like Bezos and Zuckerberg, and we now perform more than 1,000 experiments each year at our company. Finally, I now follow the 5-hour rule and spend at least two hours a day on deliberate learning.

After five years of emulating the leaders I most admire, I realized something surprising was happening to my thought process. I wasn’t just learning new strategies or hacks. I was learning a deeper and fundamentally different way of understanding reality — like I’ve accessed a hidden, secret level in the game of life. It’s thrilling to uncover deeper layers of understanding that I didn’t even know existed.

When I look back on my former self, I feel like I’m looking at a different person altogether. As previously “unsolvable” problems from my past come up again, I find I can solve many of them now. It is a great feeling to see previously insurmountable problems — both personal and professional — and realize I now have the tools to surmount them.

I’ll give you an example. In my twenties, I invested $100,000 into a business idea that never took off. Now that I understand cognitive biases — thanks to Charlie Munger — I see how the pernicious sunk cost fallacy wreaked havoc upon my decision-making. Today when I consider new business ideas, instead of just imagining how great they’re going to be, I spend just as much time envisioning what could go wrong — another Munger hack. I no longer have to remind myself to think this way anymore. I’ve internalized these concepts and now my mind actually works differently.

I once heard a coach talk about changing a client’s way of seeing the world in a way that would blow their mind. When he looked into his client’ eyes and could see him or her really getting it, he’d say, “Now, you’re in my reality!” That’s how I felt. Reality somehow feels different on an aesthetic level — as if I’m cutting through the levels of illusion and noise we normally see and getting a more direct view. The best example I can think of is that it’s like wearing augmented reality glasses that constantly feed you relevant wisdom about the situation you’re in.

Ultimately, what I’ve learned is that billionaires don’t have odd ways of talking. They, instead, are visionaries who see the world in a deeper way — one that is both incredibly effective and also learnable.

The Difference Between Average and Brilliant: Effective Mental Models

“Mental models are to your brain as apps are to your smartphone.” -Jayme Hoffman

According to Model Theory, we all always use mental models in our thinking. “Mental models are psychological representations of real, hypothetical, or imaginary situations,” according to the formal definition. Less formally, a mental model is a simplified, scaled-down version of some aspect of the world: a schematic of a particular piece of reality. A model can be represented as a blueprint, a symbol, an idea, a formula, and in many other ways. We all unconsciously create models of how the world works, how the economy works, how politics works, how other people work, how we work, how our brains work, how our day is supposed to go, and so on.

The more effective the model, the more effectively we are able to act, predict, innovate, explain, explore, and communicate. The worse the model, the more we fall prey to costly mistakes. The difference between great thinkers and ordinary thinkers is that, for ordinary thinkers, the process of using models is unconscious and reactive. For great thinkers, it is conscious and proactive.

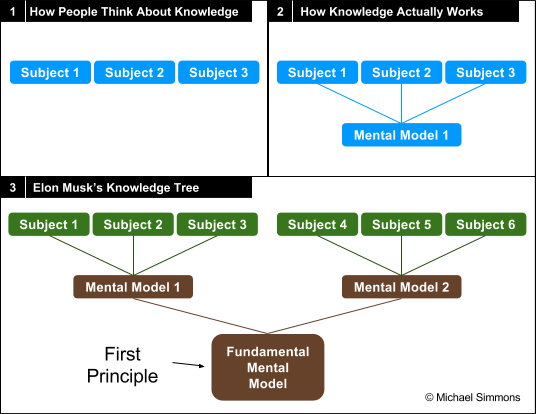

All of the extraordinary people mentioned above collect the most effective models across all disciplines, stress-test them, and creatively apply them to their daily lives. Mental models are so valuable that billionaire Ray Dalio’s only book is full of his best mental models. Charlie Mungers’ only book is packed full of his top mental models too. One of the most common pieces of advice that Elon Musk gives is to think from first principles. Mental models and first principles are similar in that they each model deeper levels of reality.

While most people think about knowledge just horizontally (ie — across fields), these great thinkers also think about knowledge vertically in terms of depth. Musk explains deep knowledge in a Reddit AMA, “It is important to view knowledge as sort of a semantic tree — make sure you understand the fundamental principles (Musk calls these ‘first principles’), i.e. the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang onto.” In another interview, Musk gives an example, “I tend to approach things from a physics framework. Physics teaches you to reason from first principles rather than by analogy.”

Physicist David Deutsch explains it even further, “It’s in the nature of foundations, that the foundations in one field are also the foundations of other fields…The way that we reach many truths is by understanding things more deeply and therefore more broadly. That’s the nature of the concept of a foundation… just as in architecture, all buildings all literally stand on the same foundation; namely the earth. All buildings stand on the same theoretical base.” By understanding verticality and depth, you can see how learning mental models connects things that were previously separate and disconnected. Just as every leaf on a tree is connected by twigs, which are connected by branches, which are connected by a tree trunk, so too are ideas connected by deeper and deeper ideas.

One of the most effective and universal mental models is the 80/20 Rule: the idea that 20 percent of inputs can lead to 80 percent of outputs. This same 80/20 idea can be applied to our personal lives (productivity, diet, relationships, exercise, learning, etc.) and our professional lives (hiring, firing, management, sales, marketing, etc). As such, you can see how the 80/20 Rule connects many disparate fields. This is what all mental models do.

To apply the 80/20 Rule, at the beginning of the day we can ask ourselves, “Of all the things on my to-do list, what are the 20 percent that will create 80 percent of the results?” When we’re searching for what to read next, we can ask ourselves, “Of all the millions of books I could buy, which ones could really change my life?” When considering who to spend time with, we can ask ourselves, “Which handful of people in my life give me the most happiness, the most meaning, and the greatest connection?” In short, consistently using the 80/20 Rule can help us get leverage by focusing on the few things that really matter and ignoring the majority that don’t.

My team and I have spent dozens of hours assembling the largest list of the most useful mental models in the world (that we’re aware of). We’ve done this by curating and combining the most useful models of other mental model collectors. To access this spreadsheet for free, visit the download page.

Mental Models Are the New Alphabet

“You can’t do much carpentry with your bare hands and you can’t do much thinking with your bare brain.” — Bo Dahlbom, philosopher and computer scientist

Evolution is so slow that a child born today is — biologically — indistinguishable from a child born 30,000 years ago. Yet, here I am typing on a MacBook, while my ancestors spent most of their time collecting berries, throwing spears, and chipping rocks. So what’s the difference between someone born 30,000 years ago and me?

Tools.

Between then and now, there has been an unprecedented explosion and evolution of tools that have collectively created modern society.

We all intuitively understand this. We all know that if we didn’t have basic tools like fire or the plow, or more complex ones like a Macbook or car, our lives would be completely different. Watch any post-apocalyptic TV or movie series and you can see how the world quickly falls apart when tools fail.

But there’s a major blindspot people have when it comes to understanding tools. Many people fail to appreciate non-physical tools — tools that they cannot touch, hear, or see. But mental tools are just as powerful and complex as physical tools. For example, consider the alphabet: the Western alphabet is a mental tool that wasn’t invented until around 1100 BC (pictorial writing systems like hieroglyphics were invented much earlier). Now we take it for granted, but at the time, it was a cutting-edge tool. Though it was adopted slowly at first — only 30 percent of the population could read and write before the printing press was invented in 1440 — once it began to spread, literate individuals had a huge leg up. In fact, literacy is now so important that it’s a national priority for all governments. That is the power of an effective mental tool.

It’s by understanding the significance of the alphabet that we can understand the significance of mental models too…

- Mental models are also fundamental and critical mental tools.

- Mental models represent large chunks of reality that can be combined together to create even more complex and useful “supermodels.” This is similar to how letters can be combined into words, which can be combined into sentences.

- Mental models should be taught early in one’s life, because nearly everything else builds on them.

- Mental models trigger higher-order thinking. This is similar to how becoming literate triggers a whole slew of higher-order thinking capabilities known as the Alphabet Effect.

As society evolves, it’s becoming more and more complex. There are more people, more tools, and more knowledge, all globally connected in complicated ways. Therefore, people who are able to model how this more complex reality works will be far more successful at navigating it. Or, as Ray Dalio says in his book, “Truth — or, more precisely, an accurate understanding of reality — is the essential foundation for any good outcome.”

People who are able to model how a complex business works in their minds are more likely to be successful business leaders, because they must understand the complex subtleties of finance (balance sheet, cash flow, and income statements), HR (recruiting and managing A+ players), product development, marketing/sales, and how they all interact with their mental models of their various stakeholders (community, customers, suppliers, employees, investors). Before an architect can build a house, he or she must first design a model of that house. That architect must have an understanding of how the electrical, plumbing, design, materials, pricing, and so on come together to create a safe, beautiful building at the right price that the market will purchase. Someone who architects a skyscraper must have a much more complex latticework of mental models than someone who models a two-bedroom house.

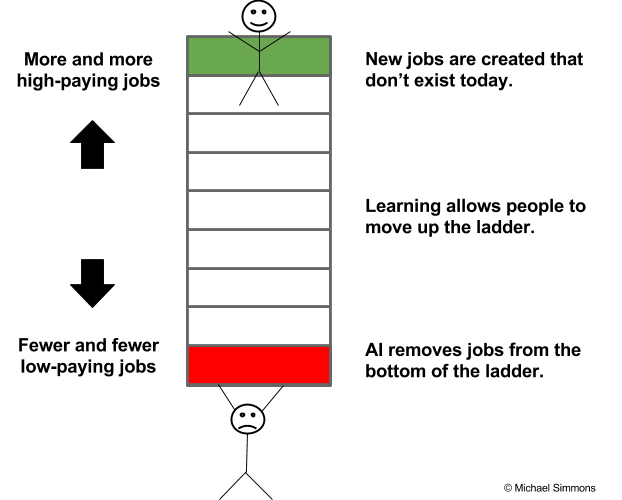

Furthermore, as people progress in their careers, they must evolve the amount, diversity, and quality of their mental models if they want to have higher and higher levels of success and impact:

Why We Should All Become Mental Model Collectors

“You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.” — Charlie Munger (self-made billionaire entrepreneur and investor)

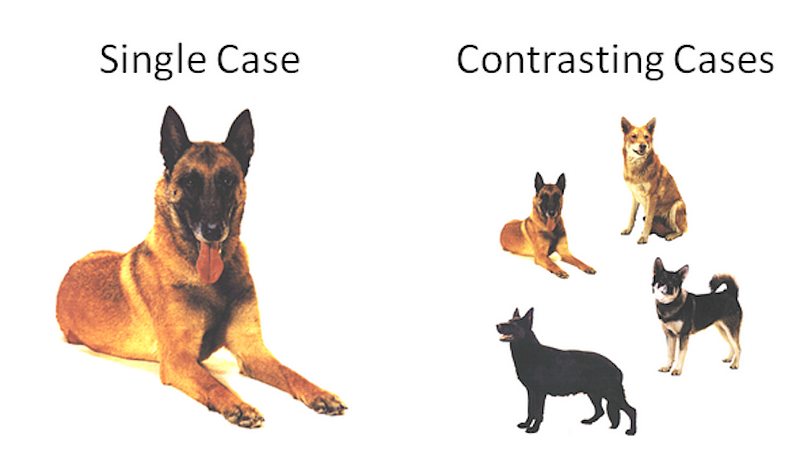

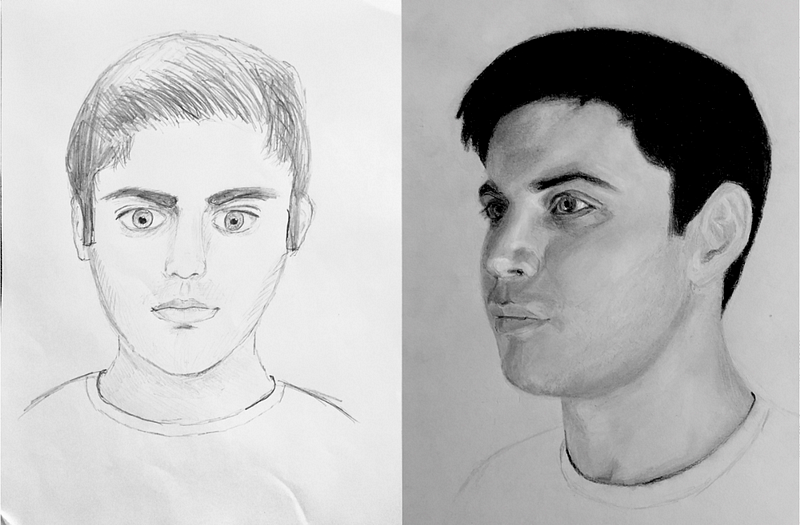

So how do you build complex, accurate mental models? Let’s me explain with a simple example: dogs. Let’s hypothetically imagine for a moment that we have no idea what a dog is. We’ve never seen or heard of one before.

Then, one day, we see a dog that looks like the image below on the left, and someone tells us that this is a dog. “Ah, I get it,” we say. “Now I know what a dog is.”

Credit: AAA Lab At Stanford University

But if we’ve only seen one dog, technically we don’t really know what a dog is. With just this single case example, our definition of a dog would be: a large black and brown animal with pointy ears that sits down, and sticks out its tongue. Bring out a Pomeranian dog and with only this mental model in mind, you are likely to ask ‘What is that?’

The numerous dog models on the right (the contrasting cases example) show us that dogs can come in all different colors, sizes, and shapes. At the same time, we can see the underlying element of “dogness” that they all share. This emergent element of “dogness” is a deeper mental model, and humans created the word “dog” to symbolize this mental model. Using that mental model, you can identify an animal as a dog even if you’ve never seen a particular breed of dog before.

What can we take away from this example that is relevant to our own life?

Many of the world’s problems result from people overgeneralizing from simplistic models just like our hypothetical one-size-fits-all “dog”. Here are three prime examples:

- Black/white thinking (you’re either a good person or a bad person with no gray area in between)

- Us/Them thinking (people outside your personal religion, nationality, or belief system are the enemy).

- All manner of stereotypes — race, gender, politics, ethnicity, etc.

Over-applying models is no different than a carpenter trying to build a house with one single hammer. All models, no matter how brilliant, are imperfect. The beauty of using multiple and diverse models is that many of the imperfections cancel each other out, allowing you to create a new “emergent” model that transcends all of the other models.

Great thinkers improve their thinking by taking in a larger quantity of information and developing a greater diversity of models. For example, a novice chess player might only know the name of each piece and how it moves across the board. But a grandmaster has memorized no less than 50,000 chunks (mental models) of increasing complexity including openings, closings, patterns throughout the game, and how one single move can lead to a particular result 10 moves or more down the line.

Many, diverse models also lead to heightened creativity. Nothing is truly original. Everything is derived by combining existing building blocks. Babies are created when a man and a woman have sex. New tools are created when pre-existing tools have “tool sex.” New ideas are created through “idea sex.” In the same way, we can build more complex mental models by combining simple mental models. For example, by understanding cause-and-effect mental models better, we can more effectively prioritize what’s important for us to do now to cause something we want in the future. The larger our base of mental models, the more creative combinations we can form. The more unique our mental models are compared to other people, the more we can think in ways that they can’t even fathom.

Through constant and diverse learning, we can organically build better and more varied models of reality. And those models will help us navigate the world far more effectively and creatively. Just as a blueprint is necessary for constructing a stable building, mental models of how the world works help us construct a better — and more stable — life.